Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Lily Hsueh, Associate Professor of Economics and Public Policy, Arizona State University

The Trump administration has given corporations plenty of convenient excuses to retreat from their climate commitments, with its moves to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, roll back emissions regulations, and scale back clean energy incentives.

But will the world’s largest corporations follow its lead?

Some multinational companies have indeed scaled back. For instance, Wells Fargo dropped its goal for the companies the bank finances to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, saying the conditions necessary for meeting that goal, such as policy certainty, consumer behavior and the pace of clean technology development, hadn’t fully materialized. Oil giant BP told investors that earlier optimism about a fast transition to renewable energy was “misplaced” given the changing regulatory environment.

However, many others, including the world’s largest retailer, Walmart, aren’t trading their long-term risk planning for Washington’s focus on short-term cost savings. They are continuing their climate policies, but often doing so quietly to avoid scrutiny.

These companies still face ongoing pressure from state and local governments, the European Union, customers and other sources to reduce their impact on the climate. They also see ways to gain a competitive advantage from investing in a cleaner future.

AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu

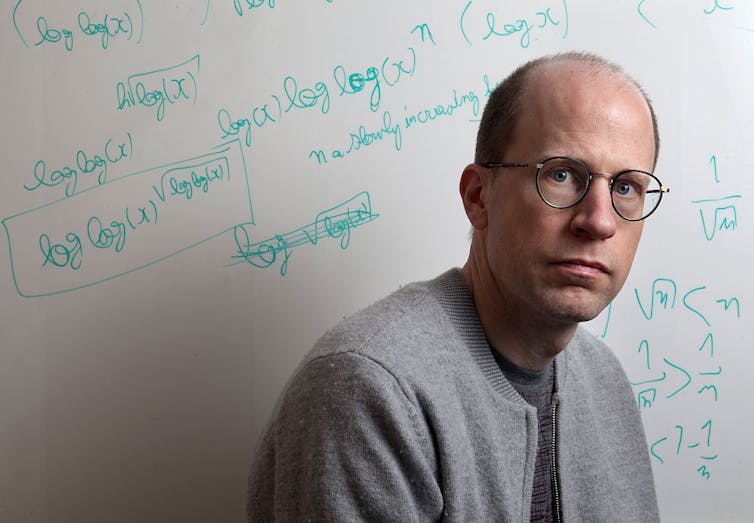

As a professor of economics and public policy, I study what motivates global businesses to engage in environmentally friendly behavior. For my new book, “Corporations at Climate Crossroads,” I interviewed executives and analyzed corporate climate actions and environmental performance of Global 500 and S&P 500 companies over the past decade.

These companies’ climate decisions are driven by a complex interplay of pressures from existing and future laws and the need to earn goodwill with employees, customers, investors, regulators and others.

States wield influence, too

In the U.S., state climate regulations affect multinational corporations. That’s especially true in California – the world’s fifth largest economy and the state with the largest population.

While President Donald Trump dismantles U.S. climate policies, California has moved in the opposite direction.

California’s newly enacted climate laws extend its cap-and-trade program, now called “cap and invest,” which is designed to ratchet down corporate emissions. They also lock in binding targets to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. And they set clean-power levels that rival the Europe Union’s Green Deal and outpace most national governments.

Other states have joined California in committing to meet the goals of the international Paris climate agreement as part of the U.S. Climate Alliance. The bipartisan coalition of 24 governors, from Arizona’s to Vermont’s, represents over half of the U.S. population.

Several states have been considering “polluters pay” laws. These laws would require companies to pay for their contributions to climate change, with the money going into funds for adaptation projects. Vermont and New York passed similar laws in 2024.

Climate laws still apply in Europe and elsewhere

Outside the U.S., several countries have climate regulations that multinational companies must meet.

The European Union aims to cut its emissions by at least 50% by 2030 through policies including binding climate reporting rules for large corporations and carbon taxes for goods entering the EU, along with initiatives to support innovation and competitiveness in clean energy and green infrastructure.

Companies also face emissions reporting requirements in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Singapore, California and cities like Hong Kong. Timelines for some of those laws have shifted, but they’re moving forward.

The International Court of Justice also issued a recent advisory opinion establishing that countries around the globe have a legal obligation to protect the climate. That decision may ultimately increase pressure on global businesses to reduce their contributions to climate change.

Multinationals put pressure on supply chains

Multinational companies’ efforts to reduce their climate impact puts pressure on their suppliers – meaning many more companies must take their climate impact into consideration.

For instance, U.S.-based Walmart operates over 10,000 stores across 19 countries and is the largest single buyer of goods in the world. That means it faces a wide range of regulations, including tracking and reducing emissions from its suppliers.

Given its enormous purchasing volume, Walmart’s procurement standards ripple through vast supply chains. In 2017, it launched Project Gigaton, aiming to cut 1 gigaton of supply-chain greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Suppliers including Nestle, Unilever, Coca Cola, Samsung and Hanes helped the company reach its target six years early through practical measures such as boosting energy efficiency, redesigning packaging, and reducing food waste.

Walmart did push back the deadlines for two of its more ambitious emissions reduction targets in 2025. At the same time, almost half of its electricity worldwide came from renewable energy in 2024, its emissions per unit of revenue fell, and it is working toward zero emissions from its operations by 2040.

There are profits to be made in clean tech

In addition to facing pressure from buyers and governments, companies see profits to be made from investing in climate-friendly clean technology.

Since 2016, investments in clean energy have outpaced that of fossil fuels globally. This trend has only hastened, with nearly twice as much invested in clean energy as fossil fuels in 2025.

Lately, myriad new business opportunities for multinational companies and start-ups alike have focused on meeting AI’s energy demand through clean energy.

From 2014 to 2024, the climate tech sector yielded total returns of nearly 200%, and U.S. investment in climate tech was still growing in 2025.

In the first half of 2025, close to one-fifth of the over 1,600 venture deals in climate tech were made by corporations for strategic reasons, such as technology access, supply chain integration, or future product offerings.

Companies look to the future

As climate risks grow alongside political headwinds, companies are facing both pushes toward and pulls away from protecting the planet from catastrophic effects. Oil and gas companies, for example, continue to invest in new oil and gas development. However, they also forecast renewable energy growth accelerating and are investing in clean tech.

The corporate leaders I interviewed, from tech companies like Intel to sporting goods and apparel companies like Adidas, talked about aligning sustainability efforts and initiatives across their business globally whenever possible.

This proactive approach allows them to more seamlessly collect data and respond to pressures arising domestically and globally, minimizing the need for costly patchwork efforts later. Moreover, global businesses know they will continue to face demands from their customers, investors and employees to be better stewards of the planet.

![]()

Lily Hsueh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Global companies are still committing to protect the climate – and they’re investing big money in clean tech – https://theconversation.com/global-companies-are-still-committing-to-protect-the-climate-and-theyre-investing-big-money-in-clean-tech-268761