Source: The Conversation – in French – By Renéo Lukic, Professeur titulaire de relations internationales, Université Laval

Tout indique que les négociations portant sur l’arrêt de la guerre en Ukraine sont au point mort. Divers enjeux laissent penser que cette situation est voulue par le Kremlin, qui peut non seulement s’en saisir afin d’accroître ses gains territoriaux et renforcer ses leviers à la table de négociations, mais aussi pour exposer les divisions au sein de l’Union européenne (UE).

Initiées depuis plusieurs mois par les États-Unis, l’Ukraine, la Russie et les États européens représentés par la Grande-Bretagne, la France et l’Allemagne, les négociations n’ont pas connu d’avancée significative vers un cessez-le-feu ou un accord de paix. Cette situation va perdurer tant que le président Poutine refusera de s’asseoir à la table de négociation avec le président Zelensky.

Professeur en relations internationales à l’Université Laval et spécialiste de la politique étrangère russe, je m’intéresse depuis 2014 à la guerre en Ukraine et à la réaction internationale vis-à-vis du conflit.

L’argument de paille

Poutine nie la légitimité de Zelensky de négocier un accord de paix, car selon lui, son homologue ukrainien refuse d’organiser les élections présidentielles dans son pays. Les élections présidentielles en Ukraine prévues en 2024 ont été repoussées jusqu’à nouvel ordre en raison de la guerre.

Il est donc facile de réfuter l’argument de Poutine, puisqu’il repose sur une simplification – voire une négation – de la réalité ukrainienne.

Rappelons que suite à l’agression russe du 24 février 2022, l’Ukraine a déclaré la loi martiale, laquelle suspend la tenue des élections. Les centaines de drones et de bombes qui s’abattent quotidiennement sur le territoire de l’Ukraine, en tuant les civiles et en détruisant les infrastructures du pays, ne permettent pas l’organisation d’élections démocratiques. L’instauration de la loi martiale en temps de guerre est une pratique ancienne et reconnue, d’ailleurs encadrée par le droit international des droits humains.

Poutine sait tout cela.

Il faut d’abord conclure un cessez-le-feu entre les belligérants afin que des élections présidentielles puissent être organisées. En repoussant les négociations directes avec l’Ukraine, le Kremlin cherche à maximiser ses gains territoriaux dans le Donbass, au détriment de l’Ukraine.

L’Union européenne méprisée

Plutôt que d’entamer des négociations directes avec l’Ukraine, Poutine s’est tourné vers le président Trump. Sa stratégie diplomatique poursuit deux objectifs. Le premier concerne l’affaiblissement à moyen terme des relations entre les États-Unis et l’UE, ainsi que le renforcement de ses propres relations avec les États-Unis. Le second objectif de la diplomatie russe vise la fissuration du soutien politique et économique de l’UE à l’égard de l’Ukraine.

Comme le montre le document de l’administration Trump intitulé « Stratégie de Sécurité Nationale » (National Security Strategy) publié le 5 décembre 2025, la perception que les États-Unis ont de l’UE est très négative, voire méprisante. L’UE est perçue comme une organisation en « déclin économique » confrontée à un « effacement civilisationnel » en raison de sa politique d’immigration hors de contrôle.

Dans une entrevue au site Politico le 8 décembre 2025, Trump a critiqué sur le même ton les dirigeants de l’UE : « Ils parlent, mais ils n’agissent pas, et la guerre ne cesse pas de s’éterniser » en Ukraine. Les mêmes reproches avaient déjà été exprimés par le vice-président des États-Unis J.D. Vance en février 2025 à la conférence de Munich. Ces deux prises de parole exemplifient le peu de poids politique dont jouit l’UE à Washington.

Déjà des milliers d’abonnés à l’infolettre de La Conversation. Et vous ? Abonnez-vous gratuitement à notre infolettre pour mieux comprendre les grands enjeux contemporains.

Réorientation des États-Unis

La nouvelle doctrine de sécurité nationale de l’administration américaine est bien reçue à Moscou. Pour Poutine, cette constellation diplomatique est perçue d’un œil favorable, car elle ouvre la porte à une entente entre la Russie et les États-Unis au détriment de l’Ukraine et de l’Europe.

Bref, un nouveau traité de Yalta, organisant une nouvelle division de l’Europe en deux blocs opposés tant désirée par Poutine, pourrait voir le jour.

Pour arriver à un accord de paix en Ukraine, les États-Unis pourraient s’inspirer des accords de Dayton. Signés en 1995, ces accords ont mis fin aux guerres en ex-Yougoslavie. Le président américain Bill Clinton (1993-2001) et son diplomate Richard Holbrook responsable des négociations ont réussi à rassembler à la table de négociation le président serbe Slobodan Milosevic, responsable des guerres en ex-Yougoslavie, le président de Croatie Franjo Tudjman et le président de Bosnie Alia Izetbegovic.

Ce format de négociations a permis de mettre fin à la guerre. La médiation diplomatique américaine était décisive pour parvenir à la fin de la guerre et elle était soutenue par les alliés européens. Trente ans après la signature des accords de Dayton, la paix perdure entre la Bosnie, la Croatie et la Serbie.

Frapper l’économie

Après le départ du président américain Joe Biden, l’UE est devenue le premier livreur de l’aide économique et militaire de l’Ukraine. Dorénavant, les armes livrées par les États-Unis à l’Ukraine sont payées par l’Ukraine et l’UE.

Pour soutenir l’effort de guerre ukrainienne, l’UE a imposé 19 paquets de sanctions économiques à la Russie, a gelé des avoirs russes, a exclu partiellement des banques russes du système Swift. De nombreuses autres mesures visant l’affaiblissement de son économie afin d’obtenir en cessez-le-feu en Ukraine ont également été mises en place.

Pour la Russie, l’UE est devenue un belligérant dangereux. Surtout après que l’UE a décidé, le 12 décembre 2025, d’immobiliser les actifs russes jusqu’à la fin de guerre en Ukraine. Ces actifs, d’une valeur de 210 milliards d’euros, se trouvent en Belgique, dans la société Euroclear, une institution financière de dépôt basée à Bruxelles. L’intention de la Commission de l’UE était d’utiliser une partie de cet argent pour faire un prêt à l’Ukraine. Après l’opposition de la Belgique, de la Hongrie, de la Slovaquie et de la Tchequie, la Commission a décidé de faire un prêt de 90 milliards d’euros à Kiev en utilisant ses propres fonds financiers.

Ce recul marquait une victoire diplomatique de Poutine contre les dirigeants européens jugés hostiles à la Russie.

Dans sa dernière conférence de presse tenue le 19 décembre 2025, Poutine a qualifié les dirigeants européens « de porcelets » décidés à provoquer « l’effondrement » de la Russie. Briser l’unité de l’UE est l’objectif primordial de la Russie, car après la diminution de l’aide américaine, l’UE reste le premier bailleur de fonds de l’Ukraine.

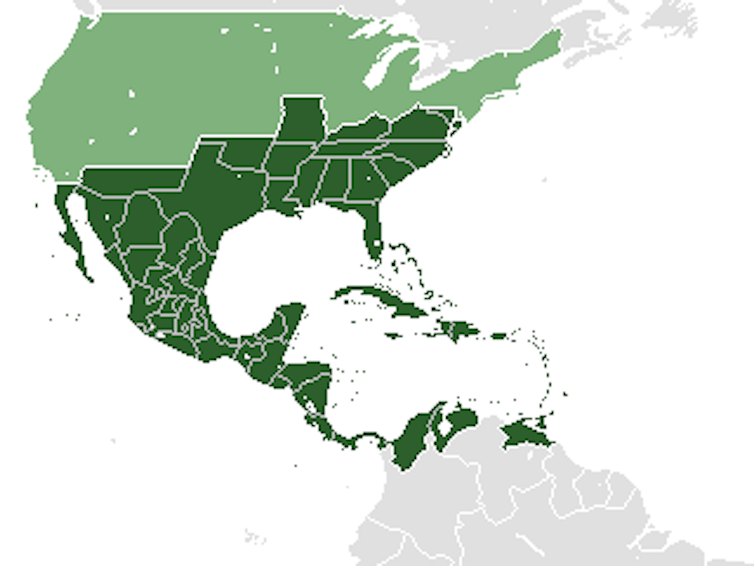

![]()

Renéo Lukic ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. Guerre en Ukraine : à la recherche d’une paix introuvable – https://theconversation.com/guerre-en-ukraine-a-la-recherche-dune-paix-introuvable-272545