Source: The Conversation – UK – By Domenico Vicinanza, Associate Professor of Intelligent Systems and Data Science, Anglia Ruskin University

For half a century, computing advanced in a reassuring, predictable way. Transistors – devices used to switch electrical signals on a computer chip – became smaller. Consequently, computer chips became faster, and society quietly assimilated the gains almost without noticing.

These faster chips enable greater computing power by allowing devices to perform tasks more efficiently. As a result, we saw scientific simulations improving, weather forecasts becoming more accurate, graphics more realistic, and later, machine learning systems being developed and flourishing. It looked as if computing power itself obeyed a natural law.

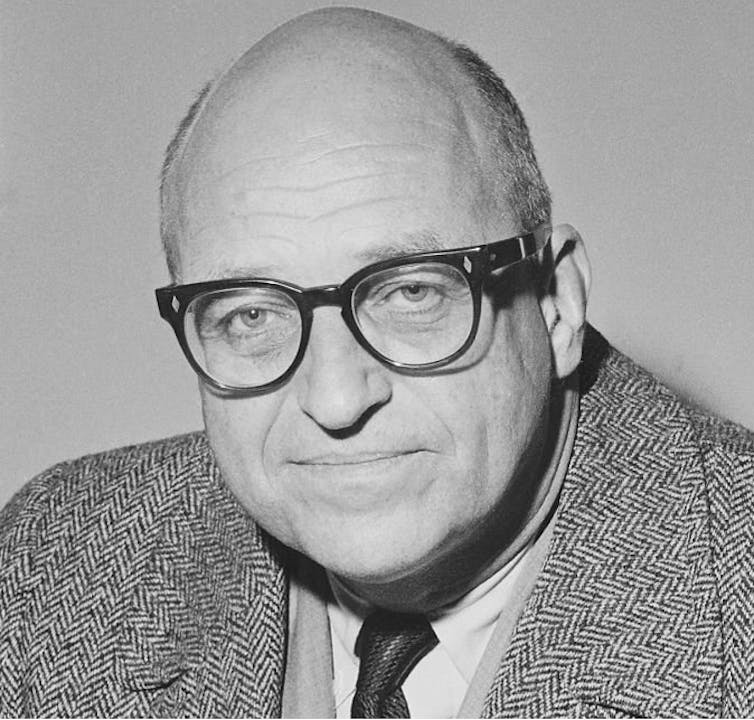

This phenomenon became known as Moore’s Law, after the businessman and scientist Gordon Moore. Moore’s Law summarised the empirical observation that the number of transistors on a chip approximately doubled every couple of years. This also allows the size of devices to shrink, so it drives miniaturisation.

That sense of certainty and predictability has now gone, and not because innovation has stopped, but because the physical assumptions that once underpinned it no longer hold.

So what replaces the old model of automatic speed increases? The answer is not a single breakthrough, but several overlapping strategies.

One involves new materials and transistor designs. Engineers are refining how transistors are built to reduce wasted energy and unwanted electrical leakage. These changes deliver smaller, more incremental improvements than in the past, but they help keep power use under control.

Another approach is changing how chips are physically organised. Rather than placing all components on a single flat surface, modern chips increasingly stack parts on top of each other or arrange them more closely. This reduces the distance that data has to travel, saving both time and energy.

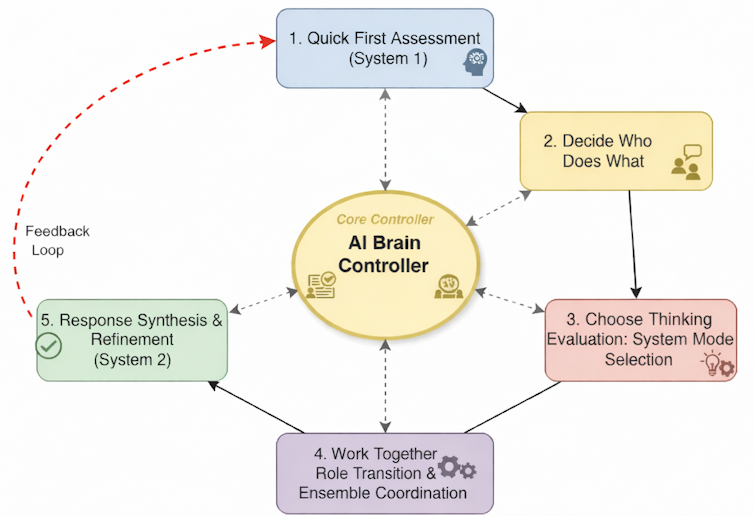

Perhaps the most important shift is specialisation. Instead of one general-purpose processor trying to do everything, modern systems combine different kinds of processors. Traditional processing units or CPUs handle control and decision-making. Graphics processors, are powerful processing units that were originally designed to handle the demands of graphics for computer games and other tasks. AI accelerators (specialised hardware that speeds up AI tasks) focus on large numbers of simple calculations carried out in parallel. Performance now depends on how well these components work together, rather than on how fast any one of them is.

Alongside these developments, researchers are exploring more experimental technologies, including quantum processors (which harness the power of quantum science) and photonic processors, which use light instead of electricity.

These are not general-purpose computers, and they are unlikely to replace conventional machines. Their potential lies in very specific areas, such as certain optimisation or simulation problems where classical computers can struggle to explore large numbers of possible solutions efficiently. In practice, these technologies are best understood as specialised co-processors, used selectively and in combination with traditional systems.

For most everyday computing tasks, improvements in conventional processors, memory systems and software design will continue to matter far more than these experimental approaches.

For users, life after Moore’s Law does not mean that computers stop improving. It means that improvements arrive in more uneven and task-specific ways. Some applications, such as AI-powered tools, diagnostics, navigation, complex modelling, may see noticeable gains, while general-purpose performance increases more slowly.

New technologies

At the Supercomputing SC25 conference in St Louis, hybrid systems that mix CPUs (processors) and GPUs (graphics processing units) with emerging technologies such as quantum or photonic processors were increasingly presented and discussed as practical extensions of classical computing. For most everyday tasks, improvements in classical processors, memories and software will continue to deliver the biggest gains.

But there is growing interest in using quantum and photonic devices as co-

processors, not replacements. Their appeal lies in tackling specific classes of

problems, such as complex optimisation or routing tasks, where finding low-energy

or near-optimal solutions can be exponentially expensive for classical machines

alone.

In this supporting role, they offer a credible way to combine the reliability of

classical computing with new computational techniques that expand what these

systems can do.

Life after Moore’s Law is not a story of decline, but one that requires constant

transformation and evolution. Computing progress now depends on architectural

specialisation, careful energy management, and software that is deeply aware of

hardware constraints. The danger lies in confusing complexity with inevitability, or marketing narratives with solved problems.

The post-Moore era forces a more honest relationship with computation where performance is not anymore something we inherit automatically from smaller transistors, but it is something we must design, justify, and pay for, in energy, in complexity, and in trade-offs.

![]()

Domenico Vicinanza does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Moore’s law: the famous rule of computing has reached the end of the road, so what comes next? – https://theconversation.com/moores-law-the-famous-rule-of-computing-has-reached-the-end-of-the-road-so-what-comes-next-273052