Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Andrea De Stefano, Assistant Professor of Forestry, Mississippi State University

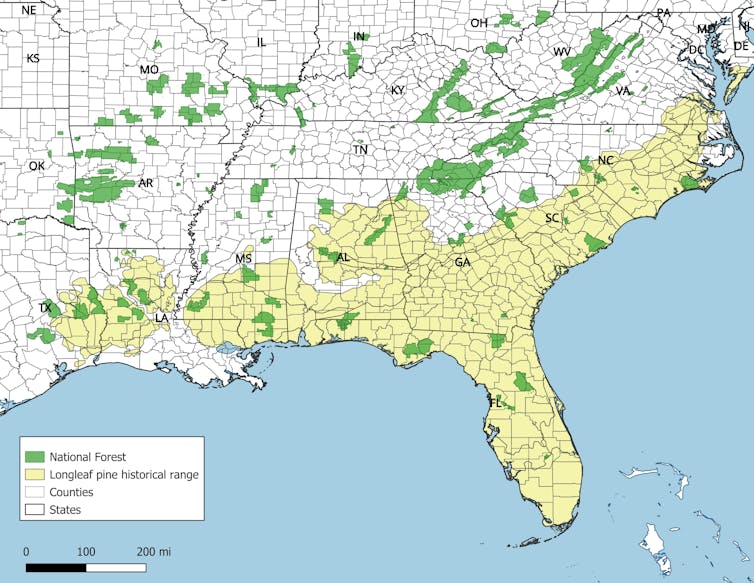

For thousands of years, one tree species defined the cultural and ecological identity of what is now the American South: the longleaf pine. The forest once stretched across 92 million acres from Virginia to Texas, but about 5% of that original forest remains. It was one of North America’s richest ecosystems, and it nearly disappeared.

As part of my job with the Mississippi State University forestry extension, I help private landowners, public agencies and nonprofit conservation groups restore these ecosystems. The forests’ story begins before European settlement, when Native peoples shaped and sustained this vast landscape using one of nature’s oldest tools: fire.

Longleaf pine trees depend on fire for survival and regeneration. Fire reduces competition from other plants, recycles nutrients into the soil and maintains the open structure of the landscape where longleaf pines grow best. In its open, grassy woodlands, red-cockaded woodpeckers, gopher tortoises, orchids, pitcher plants and hundreds of other species find homes.

Andrea De Stefano, CC BY

Native stewardship

Longleaf pine seedlings spend about three to 10 years in a low, grasslike stage, building deep roots and resisting flames that sweep across the forest floor. Regular, low-intensity fires keep the ground open and sunny, and allow an incredibly diverse understory to flourish: pine lilies, meadow beauties, white bog orchids, carnivorous pitcher plants and dozens of native grasses.

For millennia, Native American tribes intentionally set fires to keep these areas open for hunting, travel and agriculture. This practice is evident from Indigenous oral histories, early European accounts and archaeological findings. Fire was part of daily life – a tool, not a danger.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History via Wikimedia Commons

European settlers arrive

When the first Europeans made it to that part of North America, they encountered a landscape that seemed almost limitless: tall, straight pines ideal for shipbuilding; deep soils in the uplands suited for farming; and understory, the plants that grow in the shade of the forest, perfect for open-range grazing.

Longleaf pine trees became the backbone of early industries. They provided lumber, fuel and naval supplies, such as tar, pitch and turpentine, which are essential for waterproofing wooden ships. By the mid-1800s, the naval industry alone consumed millions of longleaf pines each year, especially in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida.

At the same time, livestock, especially hogs, roamed freely and caused unexpected ecological damage. Hogs rooted up the starchy, above-ground stems of young longleaf seedlings, often wiping out an area’s entire year of seedlings before they could grow beyond the grass stage.

Still, even into the mid-1800s, millions of acres of longleaf forest remained intact. That would soon change.

Corbis Historical via Getty Images

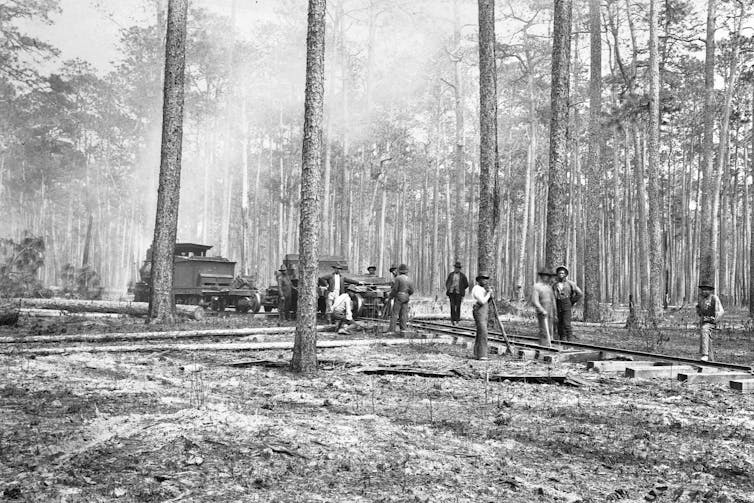

Industrial logging and the collapse of a forest

By the late 19th century, the industrial South entered a new era of logging. Railroads could reach deep into forests that were previously inaccessible. Steam-powered skidders dragged huge logs to mobile mills that could turn thousands of acres of trees into lumber in a single season. Lumber towns appeared overnight, then disappeared once the last trees were cut.

Most longleaf forests were felled between 1880 and 1930, with little thought given to regrowth. Land was cheap, timber was valuable, and scientific forestry was in its infancy. After logging, what was left on the ground at many sites burned in wildfires too hot for young longleaf pines to survive. Some of the fires were ignited accidentally by sparks from railroads or logging operations, others by lightning, and some by people attempting to clear land.

Other parcels of land were overrun by hogs or were converted to farms. Other forestland simply failed to regenerate because longleaf requires both good seed years and carefully timed burning to establish new generations of seedlings. By 1930, the once-vast longleaf forest was effectively gone.

A turning point

The early 20th century brought public debates about fire. National forestry leaders, trained in northern ecosystems where wildfire was destructive, insisted that all fire was harmful and should be quickly extinguished. Southern landowners disagreed. They had long understood that fire kept the woods open, reduced pests and improved forage.

A series of pioneering researchers, including Herbert Stoddard, Austin Cary and others, proved scientifically what Native peoples had practiced for centuries: Prescribed fire is essential for longleaf pine forests.

By the 1930s, prescribed fire began to gain acceptance among Southern landowners and wildlife biologists, and by the 1940s it was recognized by state forestry agencies and the U.S. Forest Service as a legitimate management tool. This shift marked the beginning of a slow recovery of the forest.

Yet, after the logging of old-growth longleaf pine forests ended, foresters faced challenges regenerating the trees. Early planting attempts often failed. The longleaf species grows more slowly than loblolly or slash pine, making it less attractive to industry.

Millions of acres that once supported longleaf pines were converted to fast-growing plantation pines through the mid-20th century. By 1990, only 2.9 million acres of longleaf pine forest remained.

Carl Mydans via Library of Congress

A new era of restoration

But beginning in the 1980s, research breakthroughs had begun to offer the prospect of change. Studies across the Southeast demonstrated that longleaf pine trees could be reliably planted if seedling quality, site preparation and fire timing were carefully managed.

Improved genetics – for instance, choosing those seedlings more likely to grow straight and tall and those more resistant to disease and drought – and starting seedlings in containers increased survival dramatically.

AP Photo/Chris Carlson

At the same time, landowners and agencies began to appreciate the benefits of longleaf pines. They are strong enough to withstand hurricanes, resistant to pests and disease, and provide high-quality timber and exceptional wildlife habitat. And they are compatible with grazing, need little to no fertilizer or other support to grow, and are ready to adapt to a warming, more fire-prone climate.

Today, many organizations are restoring longleaf pine trees across national forests, private lands and working farms.

Landowners are choosing the species not only for conservation but for recreation, hunting and cultural reasons.

In many parts of the South, longleaf pines have become a symbol of both heritage and resilience to hurricanes, drought, wildfire and climate change.

The longleaf pine ecosystem is more than a forest: It is the story about how people shape landscapes over centuries. It thrived under Native fire stewardship, declined under industrial exploitation, and is now returning – thanks to science, collaboration and cultural rediscovery.

The future of the longleaf pine forest will depend on continued use of prescribed fire, support for and from private landowners and recognition that restoring a complex ecosystem takes time. But across the South, the open, grassy longleaf pine ecosystems are coming back. A forest once given up for lost is becoming, again, a living emblem of the southern landscape.

![]()

Andrea De Stefano does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How fire, people and history shaped the South’s iconic longleaf pine forests – https://theconversation.com/how-fire-people-and-history-shaped-the-souths-iconic-longleaf-pine-forests-272003