Source: The Conversation – in French – By Éric Pichet, Professeur et directeur du Mastère Spécialisé Patrimoine et Immobilier, Kedge Business School

En France, un grand emprunt pourrait-il sauver la situation financière de l’État ? D’un côté, un endettement qui ne cesse de croître, de l’autre, des ménages qui épargnent toujours plus. Et si la solution était de demander aux seconds de financer plus ou moins volontairement le premier. Sur le papier, l’idée semble alléchante d’autant que le grand emprunt occupe une place particulière dans l’imaginaire français. Tentant lorsque l’épargne des ménages est une mesure de précaution pour se protéger des conséquences de l’endettement du secteur public.

L’incapacité récurrente des pouvoirs publics en France à ramener le déficit dans les critères de Maastricht a été aggravée par les deux grandes crises récentes, celle des subprimes en 2008 et celle du Covid en 2020. Cette dérive s’est encore accentuée avec l’incapacité de l’Assemblée nationale issue de la dissolution de juin 2024 à s’accorder pour voter une loi de finances qui réduirait ce déficit. En conséquence, ce dernier est attendu à 5,4 % du PIB en 2025 et encore vers 5 % en 2026, soit le plus important de la zone euro relativement au PIB, quel que soit le sort de la loi de finances pour 2026 toujours en suspens, soit très loin du seuil de 3 % fixé par le Pacte de stabilité et de croissance.

Quant à la dette publique, partie de 20 % du PIB en 1980, dernière année d’équilibre des comptes publics, elle culmine à 116 % à la fin de 2025, soit près du double du seuil du Pacte fixé à 60 % du PIB. Ce faisant, elle se situe juste après celle de la Grèce et de l’Italie.

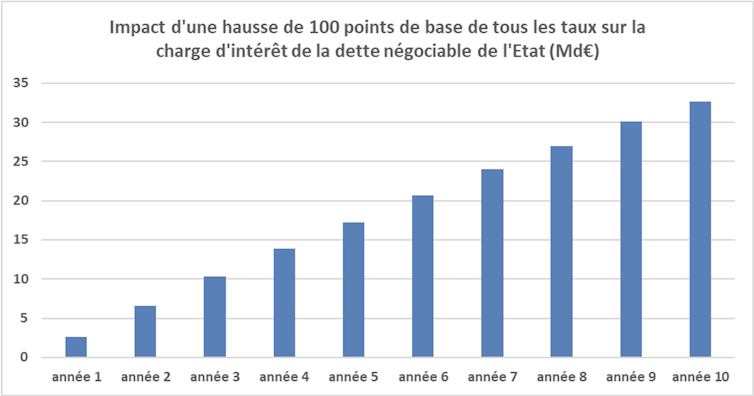

L’inquiétante envolée de la charge de la dette

La longue période de taux d’intérêt très bas voire négatifs auxquels empruntait l’État de 2009 à 2022 était la conséquence directe de l’action inédite des grandes banques centrales pour éviter une dépression mondiale à la suite de la crise des subprimes de 2008. Ce volontarisme monétaire exceptionnel s’est achevé brutalement avec la hausse brutale des taux des banques centrales en 2022-2023 pour juguler la forte inflation qui a suivi l’invasion de l’Ukraine.

À lire aussi :

De Chirac à Macron, comment ont évolué les dépenses de l’État

En conséquence, les taux d’émission des obligations françaises à dix ans sont passés de 1 % en 2022 à 3,6 % début 2026, soit à des niveaux supérieurs au Portugal et à l’Espagne et même à la Grèce. Plus grave, la charge de la dette publique (les intérêts versés chaque année aux créanciers des organismes publics) passera de 50 milliards d’euros en 2022 à 75 milliards en 2026 (dont 60 milliards pour le seul État).

Fourni par l’auteur

Source : Programme de stabilité de 2024, charge d’intérêts en comptabilité nationale, Finances publiques et économie (Fipeco).

Le précédent de l’emprunt obligatoire

Face à l’Himalaya diagnostiqué de la dette (avec raison mais un peu tard…) par François Bayrou quand il était premier ministre, les députés socialistes ont repris, au moment des débats sur l’instauration de taxe Zucman l’idée d’un emprunt forcé sur les plus riches en référence à une initiative du premier ministre Pierre Mauroy en 1983. Émis à un taux de 11 % (contre 14 % sur le marché à l’époque) celui-ci avait contraint 7 millions de contribuables à prêter 13,4 milliards de francs (soit environ 5 milliards d’euros) à hauteur de 10 % de leur impôt sur le revenu et de 10 % de leur impôt sur la fortune. Prévu pour trois ans, mais très impopulaire, car touchant également la classe moyenne supérieure, il fut remboursé par anticipation au bout de deux ans et ne fit jamais école.

Si cette idée d’un emprunt forcé a été rejetée par le gouvernement et l’Assemblée nationale le 26 novembre 2025, la piste d’un grand emprunt agite toujours les esprits d’autant que le contexte actuel rappelle celui des précédents historiques, en temps de guerre ou face à des crises budgétaires aiguës, et qu’ils ont toujours été couronnés de succès à l’émission.

L’emprunt de Thiers ou la naissance du mythe

Après la cuisante défaite de la guerre franco-prussienne de 1870-1871, le traité de Francfort du 10 mai 1871 impose à la France, outre la cession de l’Alsace-Lorraine, une indemnité de 5 milliards de francs-or (soit 70 milliards d’euros). Adolphe Thiers, le chef de l’exécutif de l’époque, émet alors un emprunt d’État au taux de 5 % sur cinquante ans garanti sur l’or.

L’engouement des épargnants a permis de payer l’indemnité allemande dès 1873 avec deux ans d’avance mettant ainsi fin à l’occupation militaire. Surtout, le succès de l’emprunt a assis la crédibilité de la toute jeune IIIe République. Puissant symbole de la résilience du pays il inspira d’autres emprunts de sorties de guerre, comme l’emprunt dit de la Libération de 1918 et celui de 1944.

L’emprunt Pinay 1952-1958 ou les délices de la rente

Premier grand emprunt du temps de paix, la rente Pinay – du nom du ministre de l’économie et des finances sous la quatrième et la cinquième République – de 1952 était destinée à sortir le pays des crises alimentaires et du logement de l’après-guerre. L’équivalent de 6 milliards d’euros a été alors levé avec un taux d’intérêt plutôt faible de 3,5 %,, mais assorti d’une indexation de son remboursement sur le napoléon en 1985 (date à laquelle l’emprunt a été complètement remboursé) et surtout une exonération d’impôt sur le revenu et sur les droits de succession.

Cette gigantesque niche fiscale pour les plus riches était d’ailleurs discrètement mise en avant par les agents de change qui conseillaient aux héritiers de « mettre leur parent en Pinay avant de le mettre en bière » pour éviter les droits de succession entraînant au passage de cocasses quiproquos familiaux lorsque le moribond reprenait des forces…

Le succès de la rente Pinay fut tel que de Gaulle, revenant au pouvoir, lui demanda de récidiver avec le Pinay/de Gaulle de 1958 destiné à sauver les finances publiques, restaurer la crédibilité de l’État et accompagner la réforme monétaire qui allait aboutir au nouveau franc de 1960.

L’emprunt Giscard, un grand emprunt coûteux pour l’État

Portant le nom du ministre des finances du président Pompidou, cet emprunt émis en 1973 rapportait 7 % et a levé l’équivalent d’environ 5,6 milliards d’euros sans avantage fiscal mais une obscure sous-clause du contrat, qui prévoyait une indexation automatique sur le lingot d’or en cas d’inflation.

L’or s’étant envolé avec la fin des accords de Bretton Woods de 1971-1974, cet emprunt coûta finalement en francs constants au moment de son remboursement en 1988 près de cinq fois ses recettes.

1993, le dernier grand emprunt

Après la crise des subprimes de 2008, Nicolas Sarkozy avait envisagé l’émission d’un grand emprunt de 22 milliards d’euros pour financer cinq grandes priorités : l’enseignement supérieur, la recherche, l’industrie, le développement durable et l’économie numérique. Il opta finalement pour un financement classique sur les marchés au motif – pertinent – qu’il aurait fallu allécher les particuliers par un taux d’intérêt supérieur.

Le dernier grand emprunt national est donc toujours aujourd’hui l’emprunt Balladur de mai 1993 rapportant 6 % sur quatre ans et destiné à mobiliser l’épargne des Français les plus aisés pour financer l’accès au travail des jeunes et la relance des travaux publics et du bâtiment. Initialement fixé à 40 milliards de francs, son succès fut tel qu’il récolta 110 milliards de francs (30 milliards d’euros) grâce à la souscription de 1,4 million d’épargnants. Le gouvernement Balladur s’étant engagé à accepter toutes les souscriptions des particuliers, il ne put satisfaire les investisseurs institutionnels.

Pas (encore) de problèmes de financement pour l’État

Un grand emprunt pourrait-il être la solution dans le contexte actuel pour financer les déficits, comme on l’entend parfois ?

Malgré la dérive des comptes publics, en France, l’État reste crédible avec une note de A+ attribuée par Standard & Poors et par Fitch, et de Aa3 par Moody’s (soit l’équivalent de 16 ou 17/20). Par ailleurs, le Trésor n’a aucune difficulté à emprunter 300 milliards d’euros par an (la moitié pour financer le déficit de l’année et l’autre pour rembourser les emprunts arrivant à échéance), si ce n’est à un taux d’intérêt supérieur de 80 points de base (0,8 %) au taux d’émission des obligations allemandes à dix ans (3,6 % contre 2,8 %). Aujourd’hui la dette publique française s’élève à environ 3 500 milliards d’euros et 55 % de la dette négociable est détenue par les non-résidents.

En France, les particuliers financent environ 10 % de cette dette publique soit 350 milliards d’euros via l’assurance-vie en euros, mais cette niche fiscale est coûteuse et régressive car elle favorise les gros patrimoines. Ainsi, selon le Conseil d’analyse économique, le manque à gagner en recettes fiscales lié à l’assurance-vie au titre des successions serait de l’ordre de 4 à 5 milliards d’euros par an.

Un grand emprunt utile en 2026 ?

Aujourd’hui, les ménages semblent se conformer à la théorie de l’économiste David Ricardo : inquiets de la situation financière du pays, ils augmentent leur taux d’épargne passé de 15 % de leurs revenus en moyenne avant la crise à 18,4 % en 2025. Et leur épargne financière, qui représente 10 % de leurs revenus, culmine à 6 600 milliards d’euros, un niveau bien supérieur à la totalité de la dette publique.

C’est pourquoi un grand emprunt national proposé par un gouvernement stable disposant d’une majorité solide rencontrerait sans doute un grand succès. Il aurait le mérite de redonner confiance au pays et de conjurer ce que The Economist identifie dans un tout récent article publié le 11 janvier 2026 comme le principal problème économique mondial : le pessimisme.

![]()

Éric Pichet ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. D’Adophe Thiers à Édouard Balladur, à qui ont profité les grands emprunts ? – https://theconversation.com/dadophe-thiers-a-edouard-balladur-a-qui-ont-profite-les-grands-emprunts-273372