Source: The Conversation – USA – By Francis Ryan, Associate Professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations, Rutgers University

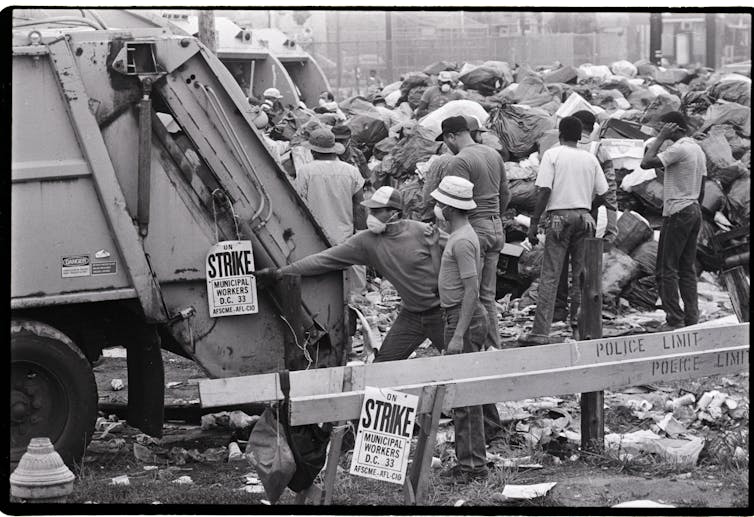

As the Philadelphia municipal worker strike enters its second week, so-called “Parker piles” – large collections of garbage that some residents blame on Mayor Cherelle Parker – continue to build up in neighborhoods across the city.

The AFSCME District Council 33 union on strike represents about 9,000 blue-collar workers in the city, including sanitation workers, 911 dispatchers, city mechanics and water department staff.

The Conversation U.S. asked Francis Ryan, a professor of labor studies at Rutgers University and author of “AFSCME’s Philadelphia Story: Municipal Workers and Urban Power in Philadelphia in the Twentieth Century,” about the history of sanitation strikes in Philly and what makes this one unique.

Has anything surprised you about this strike?

This strike marks the first time in the history of labor relations between the City of Philadelphia and the AFSCME District Council 33 union where social media is playing a significant role in how the struggle is unfolding.

The union is getting their side of the story out on Instagram and other social media platforms, and citizens are taking up or expressing sympathy with their cause.

AP Photo/Tassanee Vejpongsa

How successful are trash strikes in Philly or other U.S. cities?

As I describe in my book, Philadelphia has a long history of sanitation strikes that goes back to March 1937. At that time, a brief work stoppage brought about discussions between the city administration and an early version of the current union.

When over 200 city workers were laid off in September 1938, city workers called a weeklong sanitation strike. Street battles raged in West Philadelphia when strikers blocked police-escorted trash wagons that were aiming to collect trash with workers hired to replace the strikers.

Philadelphia residents, many of whom were union members who worked in textile, steel, food and other industries rallied behind the strikers. The strikers’ demands were met, and a new union, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, was formally recognized by the city.

This strike was a major event because it showed how damaging a garbage strike could be. The fact that strikers were willing to fight in the streets to stop trash services showed that such events had the potential for violence, not to mention the health concerns from having tons of trash on the streets.

There was another two-week trash strike in Philadelphia in 1944, but there wouldn’t be another for more than 20 years.

However, a growing number of sanitation strikes popped up around the country in the 1960s, the most infamous being the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike.

Bettmann via Getty Images

In Memphis, a majority African American sanitation workforce demanded higher wages, basic safety procedures and recognition of their union. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. rallied to support the Memphis workers and their families as part of his Poor Peoples’ Campaign, which sought to organize working people from across the nation into a new coalition to demand full economic and political rights.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King was assassinated. His death put pressure on Memphis officials to settle the strike, and on April 16 the the strikers secured their demands.

Following the Memphis strike, AFSCME began organizing public workers around the country and through the coming years into the 1970s, there were sanitation strikes and slowdowns across the nation including in New York City, Atlanta, Cleveland and Washington, D.C. Often, these workers, who were predominantly African American, gained the support of significant sections of the communities they served and secured modest wage boosts.

By the 1980s, such labor actions were becoming fewer. In 1986, Philadelphia witnessed a three-week sanitation strike that ended with the union gaining some of its wage demands, but losing on key areas related to health care benefits.

Bettmann via Getty Images

How do wages and benefits for DC33 workers compare to other U.S. cities?

DC 33 president Greg Boulware has said that the union’s members make an average salary of $46,000 per year. According to MIT’s Living Wage Calculator, that is $2,000 less than what a single adult with no kids needs to reasonably support themselves living in Philadelphia.

Sanitation workers who collect curbside trash earn a salary of $42,500 to $46,200, or $18-$20 an hour. NBC Philadelphia reports that those wages are the lowest of any of the major cities they looked at. Hourly wages in the other cities they looked at ranged from $21 an hour in Dallas to $25-$30 an hour in Chicago.

Unlike other eras, the fact that social media makes public these personal narratives and perspectives – like from former sanitation worker Terrill Haigler, aka “Ya Fav Trashman” – is shaping the way many citizens respond to these disruptions. I see a level of support for the strikers that I believe is unprecedented going back as far as 1938.

What do you think is behind this support?

The pandemic made people more aware of the role of essential workers in society. If the men and women who do these jobs can’t afford their basic needs, something isn’t right. This may explain why so many people are seeing things from the perspective of striking workers.

At the same time, money is being cut from important services at the federal, state and local levels. The proposed gutting of the city’s mass transit system by state lawmakers is a case in point. Social media allows people to make these broader connections and start conversations.

If the strike continues much longer, I think it will gain more national and international attention, and bring discussions about how workers should be treated to the forefront.

![]()

Francis Ryan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How Philadelphia’s current sanitation strike differs from past labor disputes in the city – https://theconversation.com/how-philadelphias-current-sanitation-strike-differs-from-past-labor-disputes-in-the-city-260676