Source: The Conversation – USA – By Mohamed Khalil Elhachimi, PhD Student in Mechanical Engineering, Binghamton University, State University of New York

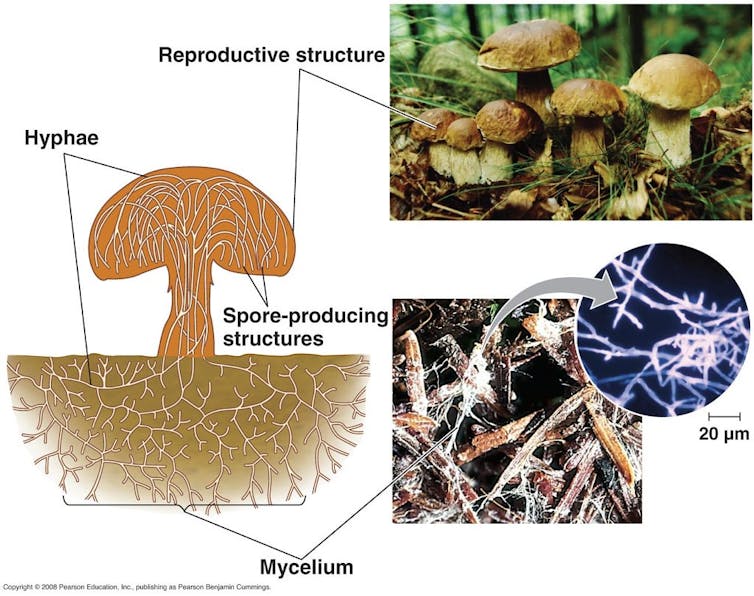

Pick up a button mushroom from the supermarket and it squishes easily between your fingers. Snap a woody bracket mushroom off a tree trunk and you’ll struggle to break it. Both extremes grow from the same microscopic building blocks: hyphae – hair-thin tubes made mostly of the natural polymer chitin, a tough compound also found in crab shells.

As those tubes branch and weave, they form a lightweight but surprisingly strong network called mycelium. Engineers are beginning to investigate this network for use in eco-friendly materials.

Milkwood.net/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Yet even within a single mushroom family, the strength of a mycelium network can vary widely. Scientists have long suspected that how the hyphae are arranged – not just what they’re made of – holds the key to understanding, and ultimately controlling, their strength. But until recently, measurements that directly link microscopic arrangement to macroscopic strength have been scarce.

I’m a mechanical engineering Ph.D. student at Binghamton University who studies bio-inspired structures. In our latest research, my colleagues and I asked a simple question: Can we tune the strength of a mushroomlike material just by changing the angle of its filaments, without adding any tougher ingredients? The answer, it turns out, is yes.

2 edible species, many tiny tests

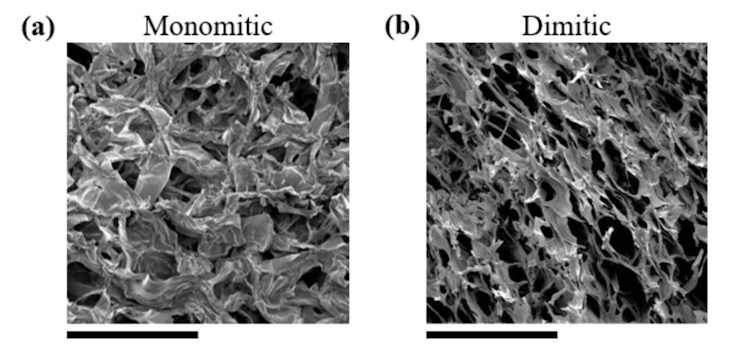

In our study, my team compared two familiar fungi. The first was the white button mushroom, whose tissue uses only thin filaments called generative filaments. The second was the maitake, also called hen-of-the-woods, whose tissue mixes in a second, thicker type of hyphae called skeletal filaments. These skeletal filaments are arranged roughly in parallel, like bundles of cables.

Mohamed Khalil Elhachimi

After gently drying the caps and stems to remove any water, which can soften the material and skew the results, we zoomed in with scanning electron microscopes and tested the samples at two very different scales.

First, we tested macro-scale compression. A motor-driven piston slowly squashed each mushroom while sensors recorded how hard the sample pushed back – the same way you might squeeze a marshmallow, only with laboratory precision.

Then we pressed a diamond tip thinner than a human hair into individual filaments to measure their stiffness.

The white mushroom filaments behaved like rubber bands, averaging about 18 megapascals in stiffness – similar to natural rubber. The thicker skeletal filaments in maitake measured around 560 megapascals, more than 30 times stiffer and approaching the stiffness of high-density polyethylene – the rigid plastic used in cutting boards and some water pipes.

Lance Cheung/USDA and edenpictures/Flickr, CC BY

But chemistry is only half the story. When we squeezed entire chunks, the direction we squeezed in mattered even more for the maitake. Pressing in line with its parallel skeletal filaments made the block 30 times stiffer than pressing across the grain. By contrast, the tangled filaments in white mushrooms felt equally soft from every angle.

A digital mushroom and twisting the threads

To separate geometry from chemistry, we converted snapshots from the microscope into a computer model using a 3D Voronoi network – a pattern that mimics the walls between bubbles in a foam. Think of ping-pong balls crammed in a box: Each ball is a cell, and the walls between cells become our simulated filaments.

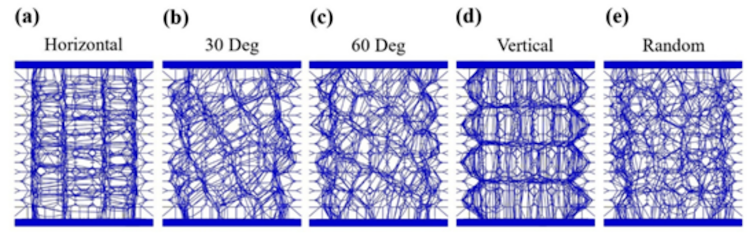

We assigned those filaments by the stiffness values measured in the lab, then virtually rotated the whole network to angles of 0 degrees, 30 degrees, 60 degrees, 90 degrees and completely random.

Horizontal (0 degrees) filaments flexed like a spring mattress. Vertical (90 degrees) filaments supported weight almost as firmly as dense wood. Simply tilting the network to 60 degrees nearly doubled its stiffness compared with 0 degrees – all without changing a single chemical ingredient.

Mohamed Khalil Elhachimi

Basically, we found that orientation alone could turn a mushy sponge into something that stands up to serious pressure. That suggests manufacturers could make strong, lightweight, biodegradable parts – such as shoe insoles, protective packaging and even interior panels for cars – simply by guiding how a fungus grows rather than by mixing in harder additives.

Greener materials – and beyond

Startups already grow “leather” made from mycelium – the threadlike fungal network – for handbags, and mycelium foam as a Styrofoam replacement.

Guiding fungi to lay their filaments in strategic directions could push performance much higher, opening doors in sectors where strength-to-weight ratio is king: think sporting goods cores, building-insulation panels or lightweight fillers inside aircraft panels.

The same digital tool kit also works for metal or polymer lattices printed layer by layer. Swap the filament properties in the model, let the algorithm pick the best angles, and then feed that layout into a 3D printer.

One day, engineers might dial up an app that says something like, “I need a panel that’s stiff north-south but flexible east-west,” and the program could spit out a filament map inspired by the humble maitake.

Our next step is to feed thousands of these virtual networks into a machine learning model so it can predict – or even invent – filament layouts that hit a targeted stiffness in any direction.

Meanwhile, biologists are exploring low-energy ways to coax real fungi to grow in neat rows, from steering nutrients toward one side of a petri dish to applying gentle electric fields that encourage filaments to align.

This study taught us that you don’t always need exotic chemistry to make a better material. Sometimes it’s all about how you line up the same old threads – just ask a mushroom.

![]()

Mohamed Khalil Elhachimi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Examining mushrooms under microscopes can help engineers design stronger materials – https://theconversation.com/examining-mushrooms-under-microscopes-can-help-engineers-design-stronger-materials-260477