Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Prachi Gala, Associate Professor of Marketing, Kennesaw State University

Faculty hiring freezes. Department budget cuts. Declining public trust. Across the United States, higher education is navigating one of its most challenging periods in decades.

Yet, quietly, something else is happening: More universities are adding chief marketing officers, or CMOs, to their top management teams.

From flagship universities to small regional colleges, public universities are increasingly hiring high-level marketing executives to oversee branding, enrollment campaigns and public communications.

Why is this happening now? And is it paying off?

As a marketing professor who researches leadership structures, I recently co-authored one of the first major studies on CMOs in higher education, along with my colleagues Aisha Ghimire and Cong Feng. In the paper, which is under review at the European Journal of Marketing, we examined thousands of data points from 167 public universities from 2010 to 2021. Our goal was to see whether having a chief marketing officer actually affected performance.

Attracting more students, if not more donations

We found that having a chief marketing officer is linked to a significant boost in enrollment. On average, student enrollment rose by 1.6% more at schools that had chief marketing officers than at those that didn’t.

That may not sound like much, but in a competitive environment where many schools are struggling to maintain their numbers, even small gains can mean millions of dollars in tuition revenue. In this context, CMOs appear to help universities better understand prospective students, fine-tune recruitment messages and coordinate outreach across multiple channels – from social media to targeted advertising.

However, when it comes to endowment growth – the other big financial lever for universities – we found no overall positive effect. In fact, in some cases, having a CMO was linked to worse performance. For example, universities whose chief marketing officers held MBAs saw their endowments grow more slowly, or even shrink, over time. The same was true of universities that brought in CMOs from outside the institution.

This doesn’t mean these executives were bad at their jobs. Instead, it suggests that traditional corporate marketing experience doesn’t always translate neatly into the relationship-building that fuels giving in higher education.

Messaging matters more in a turbulent market

If higher education were coasting along, the rise of CMOs might seem like a luxury. But the timing tells a different story.

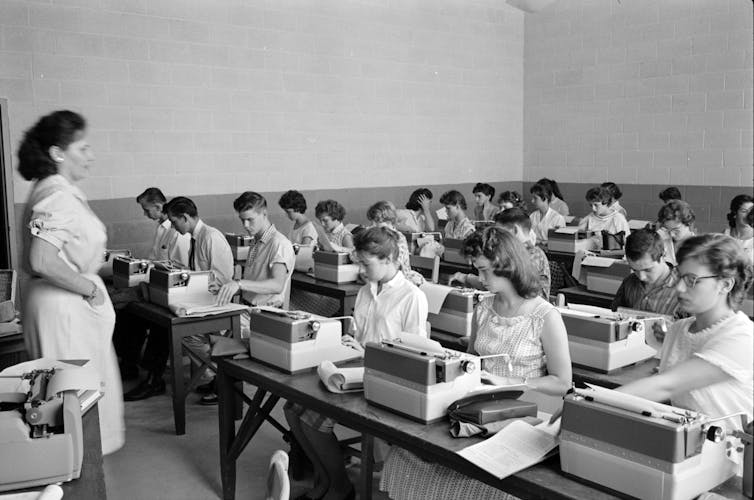

Since 2010, U.S. colleges and universities have faced declining enrollment, particularly among undergraduates. Public universities alone saw enrollment drop 4% in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated these trends – enrollment has never fully recovered – and many states have slashed public funding for higher education. Adding to the pressure, experts expect to see fewer exchange students studying at U.S. universities in the near future.

In this environment, the ability to explain the value of higher education – and a particular institution – has never been more important. Colleges and universities hire CMOs to do exactly that: define and communicate the mission, brand and unique benefits of the university to the public.

Public universities, unlike elite private institutions such as Harvard or Princeton, cannot rely solely on prestige to attract applicants and donors. They compete not only with each other but with private colleges, for-profit institutions and online programs. For them, marketing is a matter of survival.

Inside the new higher ed marketing playbook

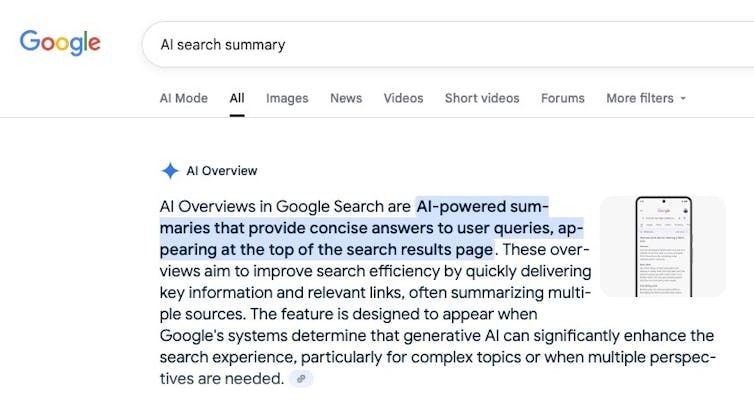

When most people think of university marketing, they imagine glossy brochures or billboards during college football season. While those still exist, much of the work is now highly targeted and data-driven.

A CMO might oversee digital ad campaigns aimed at specific students, or lead market research to identify what prospective students want from a degree. They may also handle crisis communications, alumni messaging and internal storytelling to boost morale and cohesion.

At some universities, marketing teams operate almost like internal agencies, serving multiple colleges, research centers and outreach programs. This level of coordination can be especially valuable in large, decentralized institutions where departments historically created their own messaging in isolation.

The rise of CMOs in higher education is not without controversy. Critics argue that growing executive teams — while faculty and other instructors face cuts – signals misplaced priorities. Some faculty worry that marketing language can oversimplify complex academic missions or shift a school’s focus toward revenue generation at the expense of scholarship.

The road ahead: Matching leaders to missions

Our research underscores that CMOs are most effective in specific domains, such as enrollment growth. They are not a one-size-fits-all solution for every challenge a university faces. And certain hiring decisions – such as prioritizing corporate experience over deep institutional knowledge – we believe, may have unintended consequences for fundraising.

This suggests universities need to be clear about why they’re hiring chief marketing officers and how they’ll integrate them into leadership. Without alignment between the CMO’s expertise and the institution’s strategic goals, the role risks becoming symbolic rather than meaningful.

The trend toward hiring CMOs is likely to continue, especially among public universities competing for a shrinking pool of students and constrained state and federal funding. But our findings suggest that simply adding a marketing executive is not enough. Success depends on matching the right leader to the institution’s needs and supporting them with resources, cross-campus cooperation and a clear mandate.

For some schools, that may mean seeking CMOs with deep experience in higher education advancement rather than corporate branding. For others, it may involve building stronger bridges between marketing and enrollment management, academic affairs and fundraising efforts.

The rise of CMOs isn’t a silver bullet for higher education’s enrollment and funding challenges. But it’s a sign that universities are rethinking how they present themselves to the world – and in today’s competitive, skeptical environment, that might be one of the most important strategic conversations they can have.

![]()

Prachi Gala does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why universities are hiring more chief marketing officers – even as budgets shrink – https://theconversation.com/why-universities-are-hiring-more-chief-marketing-officers-even-as-budgets-shrink-262007