Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Sloan Speck, Associate Professor of Law, University of Colorado Boulder

In December 2025, the Trump administration accelerated the process of reclassifying marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III under the Controlled Substances Act – a shift that would reduce restrictions and penalties associated with the drug.

Under the move, medical and recreational marijuana would still remain illegal at the federal level. At the state level, medical use is currently legal in 40 states and the District of Columbia, and recreational use is permitted in 24 states and Washington, D.C. While the administration touted the medical research benefits of rescheduling, the medical and recreational marijuana industry lauded it for an entirely different reason: income tax savings.

Indeed, one of rescheduling’s most significant – and most immediate – effects would be tax relief for all legal marijuana businesses in the states that host them.

But business taxes do more than raise revenue – they also create incentives that shape how companies organize and operate. For legal marijuana businesses – both medical and recreational dispensaries alike – rescheduling marijuana would relax these implicit restrictions, serving as a quiet form of deregulation that removes tax pressures that currently shape the industry’s financing, structure and compliance. From this perspective, rescheduling would cut taxes but also remove one of the federal government’s levers over an industry principally regulated by the states.

I study how tax rules shape what businesses do and the social effects of changing those rules. In my view, the tax implications of rescheduling marijuana alone are likely to have consequences that go far beyond the tax bill that businesses pay.

Why marijuana businesses are taxed differently

Under federal law, state-legal marijuana businesses face unique tax burdens.

Most businesses can deduct, or write off, ordinary and necessary expenses. For example, businesses generally can subtract the costs of rent and utilities from the income they earn. But that’s not the case for businesses that deal in Schedule I and II controlled substances, including marijuana.

In effect, legal marijuana businesses pay federal income tax on their gross income rather than their net income like other companies.

Imagine a business with US$100,000 of income before expenses and $80,000 of otherwise deductible expenses. Ordinarily, the business would pay $4,200 in tax on $20,000 of net income, assuming a 21% tax rate. The business’s cash profits would be $15,800 for the year – a healthy net profit margin.

If this hypothetical business legally sold marijuana, Section 280E of the Internal Revenue Code would deny any income tax deductions for the business’s $80,000 in expenses. This rule applies even though the business’s expenses are real costs, and even though the business is legal under state law. In this scenario, the business would owe $21,000 in tax on $100,000 of gross income. This would put the business in the red for the year, with a negative cash flow of $1,000 and a negative net profit margin.

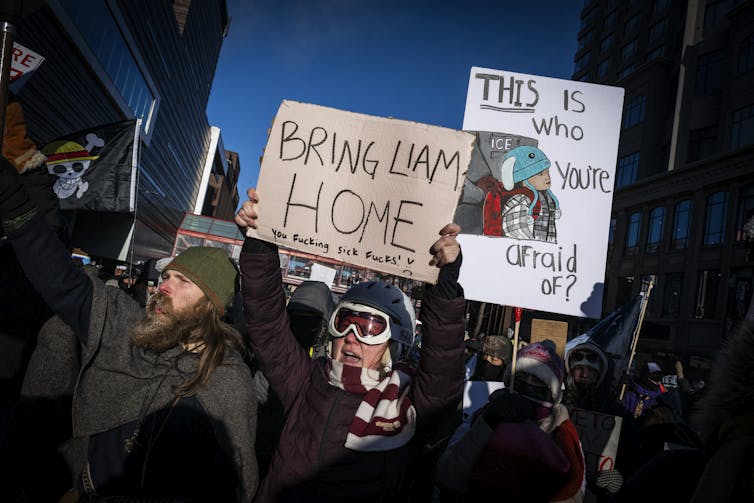

Zamek/VIEWpress/Corbis via Getty Images

For many legal marijuana businesses, making the math work isn’t a hypothetical challenge. Indeed, some enterprises have reported real-world effective tax rates as high as 80% – more than twice the top statutory rate for individuals.

This state of affairs traces to two court decisions handed down more than five decades apart. In 1927, the Supreme Court held that income from illegal activities remained subject to tax – a decision later leveraged in mob boss Al Capone’s 1931 conviction on criminal tax evasion charges. Then, in 1981, the U.S. Tax Court affirmed that illegal activities were taxable on their net income after deductions, like legal businesses. Lawmakers objected, and Congress enacted Section 280E the following year in response.

Essentially, the move gave drug traffickers a Hobson’s choice: face civil or criminal penalties for failing to properly report their income, or pay punishingly high effective tax rates. Just as Treasury Department enforcers used tax law to combat organized crime during Prohibition, tax law’s dual disincentives expressly discouraged illicit drug sales.

Because Section 280E applies only to Schedule I and II substances, rescheduling to Schedule III would tax legal marijuana businesses like other businesses. According to advocates, this would better align federal tax law with widespread state-level legalization of marijuana. In effect, rescheduling could equate to a tax break of around $2.3 billion dollars for the marijuana industry, according to one estimate.

How the tax code quietly regulates marijuana

Despite these high effective tax rates, the state-legal marijuana industry has more than tripled in revenue over the past decade and supports more than 400,000 jobs. Tax law, however, has shaped how this industry operates.

In this way, tax law serves as a form of quiet regulation – not directly, by setting licensing standards or policing potency, but indirectly. If marijuana were rescheduled, the federal government would give up this mechanism for indirect regulation.

As it currently stands, Section 280E has three important regulatory effects:

First, Section 280E limits businesses’ financing options. Like other enterprises, legal marijuana businesses need capital to grow. By constraining after-tax profits and cash flow, the status quo makes it harder for these marijuana businesses to finance growth internally using their own money from operations, known as “retained earnings.” This tax-induced capital scarcity may help explain mature legal marijuana industries’ relatively low rates of year-over-year growth. After taxes, there’s simply very little cash to reinvest.

This constraint pushes legal marijuana businesses to finance growth through external – and often unconventional – funding sources. Because marijuana businesses remain illegal under federal law, commercial banks and public capital markets may treat otherwise legal businesses as off-limits or high-risk. These businesses often turn to private capital for loans, specialized leasing arrangements and equity investments. Given the federal restrictions on marijuana, private investors tend to scrutinize these transactions closely, often insisting on protective covenants and operational restrictions.

Second, Section 280E encourages legal marijuana businesses to isolate activities that “don’t touch the plant” from marijuana production and sales. If the nonmarijuana activities are truly separate – legally, spatially and operationally – they may be able to claim business expense deductions that direct marijuana-related activities cannot.

Legal marijuana businesses have implemented these separate structures for activities from back-office support and real estate management to licensing for branding and merchandise. In addition to affecting tax burdens, these structures require ongoing operational oversight by outside parties – lawyers, accountants and other providers – and enforce the siloing of marijuana-touching activities away from other activities.

Finally, Section 280E raises the stakes of accurately accounting for the marijuana sold by these businesses. Courts have affirmed that legal marijuana businesses can reduce their gross income by the “cost of goods sold” – the direct production and acquisition costs of inventory. Even under Section 280E, these businesses can subtract the costs to grow, process and package marijuana from their sales revenue. As a result, these businesses meticulously monitor direct production costs throughout their supply chains.

This supply chain management offers another pathway for indirect regulation. Many state regulatory regimes already require inventory tracking. But Section 280E adds a financial reward for rigorous documentation, controls and auditing. Although some of this tax compliance work is mere paper-shuffling, public policy may favor multiple forms of regulation by multiple stakeholders – a diversity of oversight for an industry where lapses or inconsistencies can have serious social costs.

Federal tax rules for state-legal marijuana businesses operate as a form of indirect, or quiet, regulation: a national overlay that complements – and amplifies – state regulatory regimes. Rescheduling would remove this federal overlay by taking marijuana out of Section 280E’s reach.

From this perspective, the debate over rescheduling is about more than just tax normalization versus public health risks. Rescheduling raises bigger questions of institutional design: whether the federal government should yield one of its most practical points of leverage over the legal marijuana industry – and, if so, whether another regulatory mechanism should replace it.

![]()

Sloan Speck does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Rescheduling marijuana would be a big tax break for legal cannabis businesses – and a quiet form of deregulation – https://theconversation.com/rescheduling-marijuana-would-be-a-big-tax-break-for-legal-cannabis-businesses-and-a-quiet-form-of-deregulation-274022