Source: The Conversation – USA – By Annie Margaret, Teaching Assistant Professor of Creative Technology & Design, ATLAS Institute, University of Colorado Boulder

When graphic videos go viral, like the recent fatal shooting of Charlie Kirk, it can feel impossible to protect yourself from seeing things you did not consent to see. But there are steps you can take.

Social media platforms are designed to maximize engagement, not protect your peace of mind. The major platforms have also reduced their content moderation efforts over the past year or so. That means upsetting content can reach you even when you never chose to watch it.

You do not have to watch every piece of content that crosses your screen, however. Protecting your own mental state is not avoidance or denial. As a researcher who studies ways to counteract the negative effects of social media on mental health and well-being, I believe it’s a way of safeguarding the bandwidth you need to stay engaged, compassionate and effective.

Why this matters

Research shows that repeated exposure to violent or disturbing media can increase stress, heighten anxiety and contribute to feelings of helplessness. These effects are not just short-term. Over time, they erode the emotional resources you rely on to care for yourself and others.

Protecting your attention is a form of care. Liberating your attention from harmful content is not withdrawal. It is reclaiming your most powerful creative force: your consciousness.

Just as with food, not everything on the table is meant to be eaten. You wouldn’t eat something spoiled or toxic simply because it was served to you. In the same way, not every piece of media laid out in your feed deserves your attention. Choosing what to consume is a matter of health.

And while you can choose what you keep in your own kitchen cabinets, you often have less control over what shows up in your feeds. That is why it helps to take intentional steps to filter, block and set boundaries.

Practical steps you can take

Fortunately, there are straightforward ways to reduce your chances of being confronted with violent or disturbing videos. Here are four that I recommend:

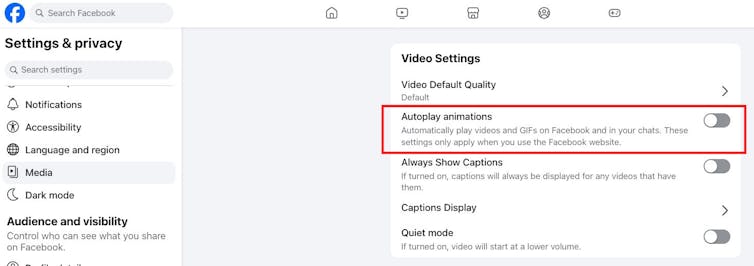

- Turn off autoplay or limit sensitive content. Note that these settings can vary depending on device, operating system and app version, and can change.

-

Use keyword filters. Most platforms allow you to mute or block specific words, phrases or hashtags. This reduces the chance that graphic or violent content slips into your feed.

-

Curate your feed. Unfollow accounts that regularly share disturbing images. Follow accounts that bring you knowledge, connection or joy instead.

-

Set boundaries. Reserve phone-free time during meals or before bed. Research shows that intentional breaks reduce stress and improve well-being.

Screen capture by The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Reclaim your agency

Social media is not neutral. Its algorithms are engineered to hold your attention, even when that means amplifying harmful or sensational material. Watching passively only serves the interests of the social media companies. Choosing to protect your attention is a way to reclaim your agency.

The urge to follow along in real time can be strong, especially during crises. But choosing not to watch every disturbing image is not neglect; it is self-preservation. Looking away protects your ability to act with purpose. When your attention is hijacked, your energy goes into shock and outrage. When your attention is steady, you can choose where to invest it.

You are not powerless. Every boundary you set – whether it is turning off autoplay, filtering content or curating your feed – is a way of taking control over what enters your mind. These actions are the foundation for being able to connect with others, help people and work for meaningful change.

More resources

I’m the executive director of the Post-Internet Project, a nonprofit dedicated to helping people navigate the psychological and social challenges of life online. With my team, I designed the evidence-backed PRISM intervention to help people manage their social media use.

Our research-based program emphasizes agency, intention and values alignment as the keys to developing healthier patterns of media consumption. You can try the PRISM process for yourself with an online class I am launching through Coursera in October 2025. You can find the course, Values Aligned Media Consumption, by searching for Annie Margaret at the University of Colorado Boulder on Coursera. The course is aimed at anyone 18 and over, and the videos are free to watch.

![]()

Annie Margaret works for/consults to Post Internet Project. She receives funding from University of Colorado Boulder PACES grant.

– ref. How to avoid seeing disturbing content on social media and protect your peace of mind – https://theconversation.com/how-to-avoid-seeing-disturbing-content-on-social-media-and-protect-your-peace-of-mind-265178