Source: The Conversation – USA – By Ari Koeppel, Earth Sciences Postdoctoral Scientist and Adjunct Associate, Dartmouth College

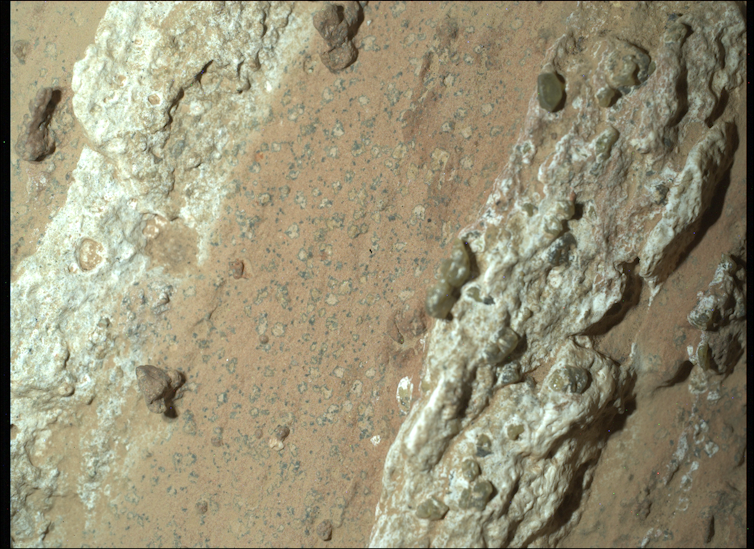

NASA’s search for evidence of past life on Mars just produced an exciting update. On Sept. 10, 2025, a team of scientists published a paper detailing the Perseverance rover’s investigation of a distinctive rock outcrop called Bright Angel on the edge of Mars’ Jezero Crater. This outcrop is notable for its light-toned rocks with striking mineral nodules and multicolored, leopard print-like splotches.

By combining data from five scientific instruments, the team determined that these nodules formed through processes that could have involved microorganisms. While this finding is not direct evidence of life, it’s a compelling discovery that planetary scientists hope to look into more closely.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

To appreciate how discoveries like this one come about, it’s helpful to understand how scientists engage with rover data — that is, how planetary scientists like me use robots like Perseverance on Mars as extensions of our own senses.

Experiencing Mars through data

When you strap on a virtual reality headset, you suddenly lose your orientation to the immediate surroundings, and your awareness is transported by light and sound to a fabricated environment. For Mars scientists working on rover mission teams, something very similar occurs when rovers send back their daily downlinks of data.

Several developers, including MarsVR, Planetary Visor and Access Mars, have actually worked to build virtual Mars environments for viewing with a virtual reality headset. However, much of Mars scientists’ daily work instead involves analyzing numerical data visualized in graphs and plots. These datasets, produced by state-of-the-art sensors on Mars rovers, extend far beyond human vision and hearing.

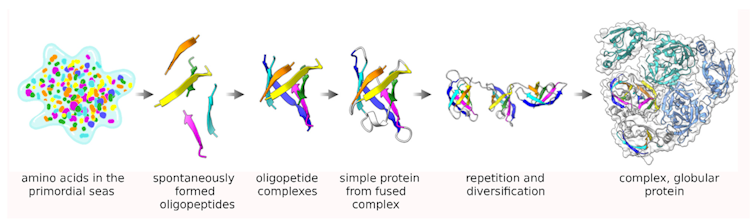

Developing an intuition for interpreting these complex datasets takes years, if not entire careers. It is through this “mind-data connection” that scientists build mental models of Martian landscapes – models they then communicate to the world through scientific publications.

The robots’ tool kit: Sensors and instruments

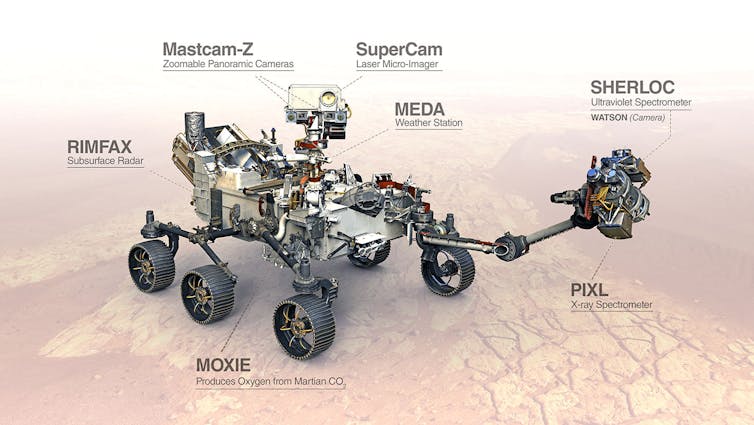

Five primary instruments on Perseverance, aided by machine learning algorithms, helped describe the unusual rock formations at a site called Beaver Falls and the past they record.

Robotic hands: Mounted on the rover’s robotic arm are tools for blowing dust aside and abrading rock surfaces. These ensure the rover analyzes clean samples.

Cameras: Perseverance hosts 19 cameras for navigation, self-inspection and science. Five science-focused cameras played a key role in this study. These cameras captured details unseeable by human eyes, including magnified mineral textures and light in infrared wavelengths. Their images revealed that Bright Angel is a mudstone, a type of sedimentary rock formed from fine sediments deposited in water.

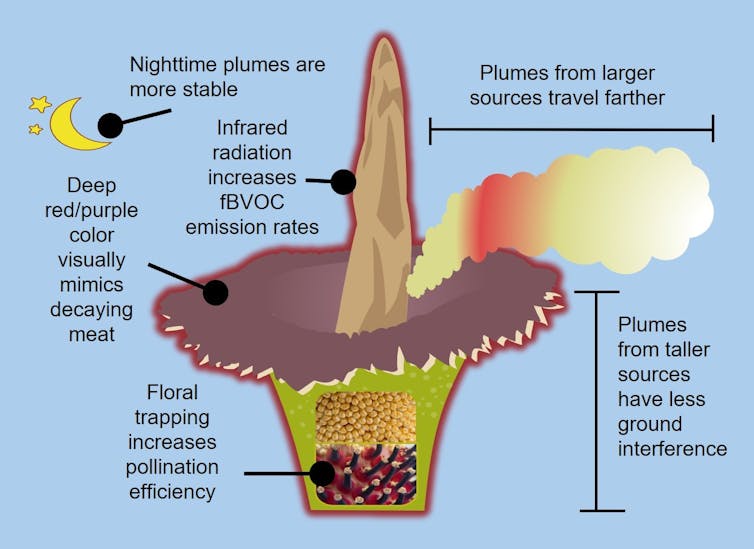

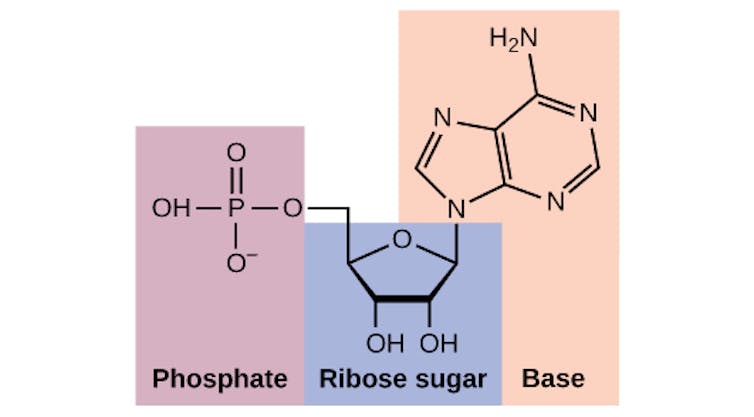

Spectrometers: Instruments such as SuperCam and SHERLOC – scanning habitable environments with Raman and luminescence for organics and chemicals – analyze how rocks reflect or emit light across a range of wavelengths. Think of this as taking hundreds of flash photographs of the same tiny spot, all in different “colors.” These datasets, called spectra, revealed signs of water integrated into mineral structures in the rock and traces of organic molecules: the basic building blocks of life.

Subsurface radar: RIMFAX, the radar imager for Mars subsurface experiment, uses radio waves to peer beneath Mars’ surface and map rock layers. At Beaver Falls, this showed the rocks were layered over other ancient terrains, likely due to the activity of a flowing river. Areas with persistently present water are better habitats for microbes than dry or intermittently wet locations.

X-ray chemistry: PIXL, the planetary instrument for X-ray lithochemistry, bombards rock surfaces with X-rays and observes how the rock glows or reflects them. This technique can tell researchers which elements and minerals the rock contains at a fine scale. PIXL revealed that the leopard-like spots found at Beaver Falls differed chemically from the surrounding rock. The spots resembled patterns on Earth formed by chemical reactions that are mediated by microbes underwater.

NASA

Together, these instruments produce a multifaceted picture of the Martian environment. Some datasets require significant processing, and refined machine learning algorithms help the mission teams turn that information into a more intuitive description of the Jezero Crater’s setting, past and present.

The challenge of uncertainty

Despite Perseverance’s remarkable tools and processing software, uncertainty remains in the results. Science, especially when conducted remotely on another planet, is rarely black and white. In this case, the chemical signatures and mineral formations at Beaver Falls are suggestive – but not conclusive – of past life on Mars.

There actually are tools, such as mass spectrometers, that can show definitively whether a rock sample contains evidence of biological activity. However, these instruments are currently too fragile, heavy and power-intensive for Mars missions.

Fortunately, Perseverance has collected and sealed rock core samples from Beaver Falls and other promising sites in Jezero Crater with the goal of sending them back to Earth. If the current Mars sample return plan can retrieve these samples, laboratories on Earth can scrutinize them far more thoroughly than the rover was able to.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Investing in our robotic senses

This discovery is a testament to decades of NASA’s sustained investment in Mars exploration and the work of engineering teams that developed these instruments. Yet these investments face an uncertain future.

The White House’s budget office recently proposed cutting 47% of NASA’s science funding. Such reductions could curtail ongoing missions, including Perseverance’s continued operations, which are targeted for a 23% cut, and jeopardize future plans such as the Mars sample return campaign, among many other missions.

Perseverance represents more than a machine. It is a proxy extending humanity’s senses across millions of miles to an alien world. These robotic explorers and the NASA science programs behind them are a key part of the United States’ collective quest to answer profound questions about the universe and life beyond Earth.

![]()

Ari Koeppel previously received funding from NASA science grants. He is affiliated with The Planetary Society. Any views represented in this article are those of the author. The budget cuts do not directly affect the author’s work and he is not currently formally connected to the rover campaign.

– ref. Mars rovers serve as scientists’ eyes and ears from millions of miles away – here are the tools Perseverance used to spot a potential sign of ancient life – https://theconversation.com/mars-rovers-serve-as-scientists-eyes-and-ears-from-millions-of-miles-away-here-are-the-tools-perseverance-used-to-spot-a-potential-sign-of-ancient-life-265144