Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Diana Chigas, Professor of the Practice in International Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, Tufts University

For nearly half a century, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act has made it illegal for U.S. citizens and companies to bribe foreign officials. Since 1998, that has been the case for foreign companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges or acting in the U.S., too.

Under the Trump administration, however, expectations are changing. In February 2025, an executive order froze new investigations for 180 days, arguing that the act has been “stretched beyond proper bounds” and “harms American economic competitiveness.” The president ordered a review of enforcement guidelines to ensure they advance U.S. interests and competitiveness.

The Department of Justice’s revised guidelines, issued in June 2025, prioritize cases that are tied to cartels and other transnational criminal organizations, harm U.S. companies or their “fair access to compete,” or involve “infrastructure or assets” important for national security.

Whatever impact the new guidelines will have on anti-corruption prosecutions globally, which is still unclear, the impact on the actual level of corruption will likely be small. Legal rules and sanctions designed to deter, find and punish “bad apples” have had limited success in many parts of the world. Yet the United States’ retreat from leadership could set back momentum for addressing the root causes of corruption.

New anti-corruption norm, but limited change

In 1977, when the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act was signed into law, the U.S. was alone in criminalizing bribery of foreign officials. Since then, and especially since the end of the Cold War, there’s been a paradigm shift.

Today, a global infrastructure of treaties and institutions obligates countries to criminalize corruption, adopt measures to prevent it and cooperate to recover stolen assets. All but a few members of the United Nations have adopted the U.N. Convention Against Corruption. Substantial amounts of international aid have also been allocated to strengthen anti-corruption efforts. In 2021 alone, the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development invested over US$7.5 billion for reforms related to fighting corruption, from anti-corruption courts to public financial management.

Yet global trends in corruption, widely defined as the “abuse of entrusted power for personal gain,” are not improving. On the 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index, the most widely used global ranking of public sector corruption, two-thirds of countries scored below 50 on a scale where 0 is “very corrupt” and 100 is “very clean.” And while 32 countries had reduced corruption since 2012, 148 had either stayed the same or gotten worse.

Corruption, it turns out, can be stubbornly resistant to “best practices.”

BSIP/Universal Images Group Via Getty Images

A few examples illustrate this “whack-a-mole” dynamic. Medical personnel in Ugandan hospitals began to solicit “gifts” and “appreciation” after the government imposed greater oversight and penalties for bribery. A study of World Bank efforts in over 100 developing countries to clean up procurement corruption found that gains in one area were canceled out when government buyers started to use procedures not subject to the new rules. In my own research, my co-authors and I found that civil servants developed innovative ways to avoid enforcing a law requiring public employees convicted of corruption to be fired.

More than ‘bad apples’

I have spent the past 10 years trying to understand this paradox. One key factor we (and many others) found is that most conventional anti-corruption tools are addressing the wrong problem.

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and similar measures focus on preventing, detecting and punishing individual acts of corruption. Rules requiring reporting and asset declarations, monitoring and oversight, and criminal penalties for corruption belong to this category. These tools try to limit the power people have over decisions and resources and increase accountability and transparency.

This approach works where corrupt acts are sporadic, opportunistic deviations from the norm by “bad apples” acting to enrich themselves. It also assumes that rule of law and robust institutions exist.

Ezra Acayan/Getty Images

This is not the case in much of the world – especially in fragile and conflict-affected states where corruption is endemic. By “endemic,” I mean not just that corruption is widespread, but that it is embedded in politics and the economy – a “team effort” within broad networks, with informal rules of the game. As an Afghan official reportedly told U.S. Embassy officials in 2010, endemic corruption “is not just a problem for the system of governance … it is the system of governance.”

What makes the conventional anti-corruption tool kit so ineffective in contexts of endemic corruption?

#1. It does not pay to follow the rules. Without trusted leaders and institutions to implement the law, it is difficult for people to behave honestly, as they don’t trust that others will do the same. Corruption, in this sense, is a “collective action” problem. If corruption is the norm, not the exception, the short-term costs of sticking to the rules are too high.

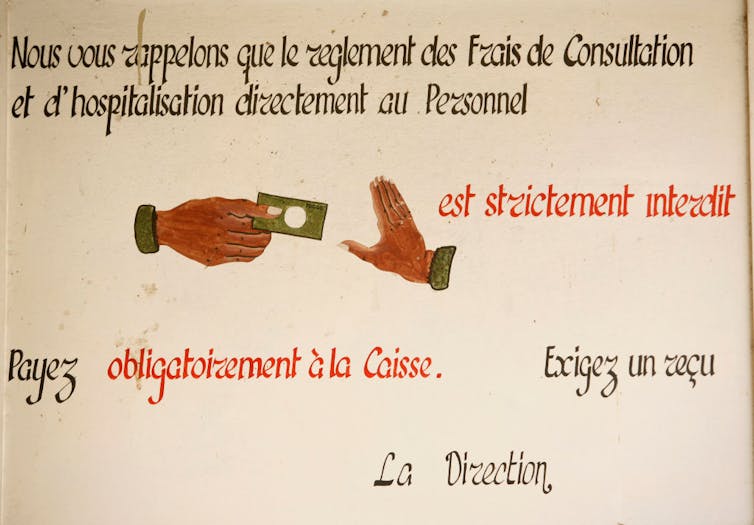

#2. Corruption serves a useful function – even when it undermines the public good. Even when people believe it’s wrong, corruption can solve problems that seem unsolvable in their current system. For example, health workers in Nigeria often ask for bribes because their salaries are low and clinics lack needed supplies. The money helps them fulfill family obligations and make clinics work. Similarly, politicians often practice patronage because it helps them redistribute wealth to retain supporters and stabilize conflict. Unless dysfunction is addressed, incentives to bypass the rules remain.

#3. Informal institutions prevail over formal rules. When a government cannot be relied upon to provide security, services or livelihoods, people rely on their personal networks to survive. As a judge in the Central African Republic told our research team, “If someone [within your social network] asks for a service, you are required to do it, even if it goes against your own ethics. To refuse is to put oneself in opposition [to one’s clan] and this can be dangerous.”

Loss of leadership

This does not mean that conventional anti-corruption approaches are completely ineffective or irrelevant.

But they aren’t enough on their own. They work best hand in hand with interventions that address motivating factors – from low pay to a lack of livelihoods not dependent on corruption, to social norms that motivate people to seek bribes or make them hesitate to enforce the rules.

Over the past few years, momentum has built to develop these new approaches – though it is still early to assess their effectiveness. Some focus on fixing government dysfunction. Others help unite people and groups trying to resist corruption. Some projects support “horizontal” monitoring by peer firms or communities, instead of government regulation, or try to “nudge” behaviors or change social norms.

The limitations of existing anti-corruption approaches suggest that more limited enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act is not likely, by itself, to worsen global corruption. But the loss of U.S. leadership may.

The U.S. role in anti-corruption progress cannot be understated – as a leader in “policing” foreign corruption, a model for other countries’ laws and institutions, and a leading donor. It is still unclear whether others – such as the U.K., the most likely and dedicated candidate – can fill the gap.

Equally concerning, in my view, is the danger that the U.S. turn to a more self-serving view of anti-corruption efforts may encourage a corrupt use of anti-corruption enforcement. Many authoritarian governments have weaponized anti-corruption laws to target political opponents through selective prosecutions.

If the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act is used this way, this could not only undermine the legitimacy of global anti-corruption norms but exacerbate conflict and fuel democratic backsliding at home and abroad.

![]()

Diana Chigas receives funding for her research from The MacArthur Foundation, Transparency International Canada and the Wellspring Philanthropic Fund through Besa Global, Inc., a social enterprise in Canada dedicated to improving anti-corruption effectiveness in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

– ref. Conventional anti-corruption tools often fail to address root causes – but loss of US leadership could still spell trouble for efforts abroad – https://theconversation.com/conventional-anti-corruption-tools-often-fail-to-address-root-causes-but-loss-of-us-leadership-could-still-spell-trouble-for-efforts-abroad-263894