Source: The Conversation – UK – By Edward Lavender, Postdoctoral Researcher, Aquatic Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology; Edinburgh Napier University

The development of miniaturised electronic tags that can be attached to animals has been one of the most spectacular developments for biology, environmental science and wildlife conservation in the 21st century.

In a new study published in the journal Science Advances, my colleagues and I unlocked new opportunities to track animals underwater, using advanced statistical techniques also adopted in military and aerospace contexts.

Animals are tracked all over the world: in deserts, grasslands, forests, rivers, lakes and oceans, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Satellite-based tags, which transmit the locations of tagged animals, have been particularly important, providing an unprecedented “eye on life and planet”.

But reconstructing the movements of animals that live exclusively underwater without ever surfacing remains a great challenge.

Beneath the waves, satellite-based trackers don’t work because the transmissions can’t pass effectively through water. So scientists have to rely on indirect observations to study animal movements, like detections on hydrophones or animal-borne depth measurements.

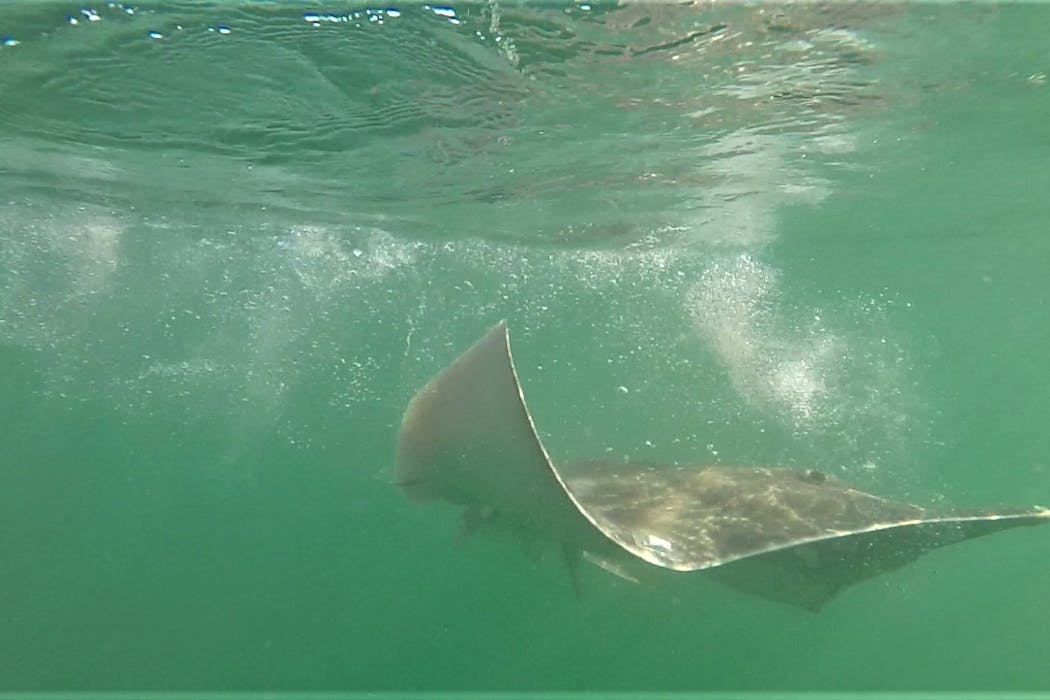

In Scotland, we have spent over a decade studying the movements of the critically endangered flapper skate (Dipturus intermedius). Skates, and their close cousins the sharks, are an ancient and diverse group of animals. The flapper skate is the world’s largest skate.

James Thorburn, CC BY-NC-ND

Growing over two metres long and 100kg in weight, flapper skate can be found roaming in the darkness over the seabed in the north-east Atlantic. It’s thought they may live for over 40 years.

For generations, flapper skate was mislabelled as common skate. It was only in 2010 that the common skate was shown, genetically, to comprise two species: the flapper and the common blue skate. Both are thought to be critically endangered due to historical overfishing.

In 2016, the Loch Sunart to the Sound of Jura marine protected area in Scotland was established with fisheries restrictions to conserve flapper skate. It’s an inspiring place. The mountains of Scotland’s west coast rise dramatically out of the sea, which is peppered with islands and inlets. But the landscape is just as rugged underwater, where flapper skate roam in the deep.

Listening for animals underwater

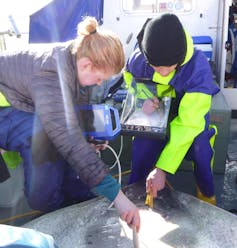

Since 2016, we’ve been tracking flapper skate in Scotland using a technology called passive acoustic telemetry. It’s used in aquatic environments all over the world to track fish and other animals underwater. Animals are tagged with acoustic transmitters and networks of listening stations (hydrophones) are deployed that can detect those signals when tagged animals swim within range.

For flapper skate, we also deploy pressure sensors that record their depths. The challenge has been to integrate these different kinds of information to reconstruct individual movements, deep below the surface.

James Thorburn, CC BY-NC-ND

In our study, we took a step forward to solving this problem with a powerful statistical approach. It’s quite intuitive. We treat animals as “particles” that can swim around and reproduce or dwindle. Particles that move in ways that align with the data we collected are more prolific breeders and come to dominate the (digital) population. Similar techniques can be used in military tracking because the data updating step, which drives particle frequency, can happen in real time.

It’s just like building a sandcastle. We have a bunch of particles and the collection of all these particles forms a 3D map of an animal’s possible locations.

This is a great advance for conservation. By integrating information from multiple technologies into the algorithm, we can build up more detailed pictures of animal movements in the ocean. We can map their patterns of space use, work out how long they spend in particular habitats and use this information to inform conservation action.

For flapper skate, we found that they spend a remarkable amount of time in the protected area, so the fisheries restrictions there should support local recovery. We also identified specific hotspots beyond protected areas, where additional management may be beneficial. This work takes us another step towards targeted, data-driven conservation.

We’re now refining our methods and software implementations to reduce computing time. We’re also further developing our analyses to reconstruct detailed animal tracks, identify egg nurseries and build immersive virtual reality experiences of the lives of animals underwater. There is still much more to learn about animals in the deep.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

The study was funded by Eawag, using data made available via the Movement Ecology of Flapper Skate project. Data collection was funded by the Marine Directorate, NatureScot and the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland.

– ref. Introducing a new way to track animals in the deep blue – https://theconversation.com/introducing-a-new-way-to-track-animals-in-the-deep-blue-270592