Source: The Conversation – UK – By Eamon McCrory, Professor of Developmental Neuroscience and Psychopathology, UCL

Between 2014 and 2024, the proportion of people aged 16–24 in England experiencing mental health issues rose from 19% to 26%.

This means over 1.6 million young people – enough to fill Wembley Stadium 18 times over – are affected by mental ill-health today.

Social media is often at the centre of conversations about what’s driving this trend. But while our increasingly digital lives are part of the story, the bigger picture is more complex. Young people are arguably spending more time online partly because the real world has less and less to offer them.

At the heart of their declining wellbeing is the hollowing out of the real-world infrastructure that supports healthy social development, with social lives becoming increasingly fragile and “thinned”.

This “social thinning”, a term we developed in research exploring trauma, includes fewer opportunities to play, take risks and build supportive relationships. This thinning, we believe, has worrying implications for development and mental health.

One of us (Eamon McCrory) is a neuroscientist who has spent years studying risk and resilience and brain systems that develop across adolescence. During this period, the brain refines the systems that help us understand others, form a clear sense of self and regulate our emotions.

Teenagers are wired to explore friendships, navigate complex social groups and practice handling conflict and rejection. These experiences help young people develop agency and independence.

But developing these abilities depends on spending time in a wide range of real social environments with different kinds of relationships, from casual interactions to close friendships.

When chances to practise these skills shrink, it can lead to loneliness and consequences for development. It can become harder to trust others, feel connected to peers or manage strong emotions.

For example, one study used the pandemic as an opportunity to test the effect of a significant reduction in social connections between teenagers. The researchers found that trust was low in adolescents during lockdown, and this in turn was associated with high levels of stress.

In other words, the evidence points to deprivation of social connection as having developmental consequences, and over time, an increased risk of mental health difficulties.

Thinning social worlds

The real-world experiences that support these crucial neurological processes have been steadily declining. Between 2011 and 2023, over 1,200 council-run youth centres in England and Wales closed, and £1.2 billion has been stripped from youth service budgets since 2010 in England. Meanwhile, parks and open spaces have suffered from underinvestment.

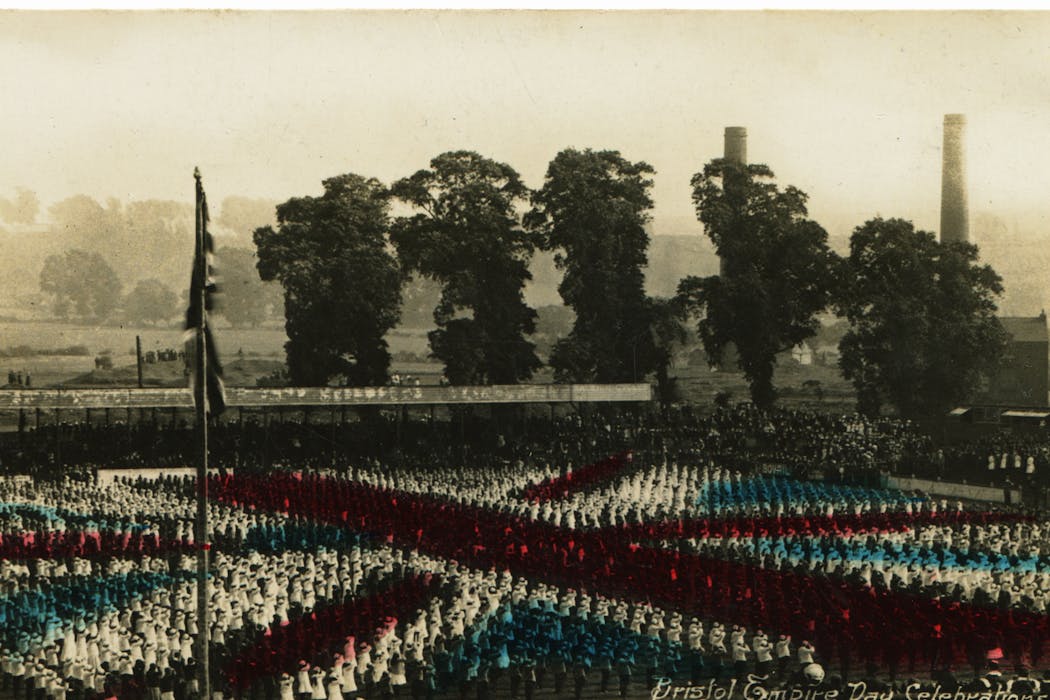

Knights Lane/Shutterstock

Cultural shifts have also had an impact. It has been suggested that fears about safety and a desire to minimise risks for their children have produced a “risk-averse” parenting culture. In schools, rising academic pressures and an emphasis on achievement have come at the expense of play and exploration.

Research suggests that children today have significantly less freedom to roam, play outdoors, or gather with peers than previous generations.

The environments in which young people can explore, fail safely and develop social mastery have been radically narrowed. It is into an already thinning social ecosystem that digital platforms enter.

Digital help and harm

Despite many arguments to the contrary, digital spaces are not inherently harmful. They can offer connection, self-expression and community.

This can be particularly true for those marginalised offline, with research suggesting social media can actually support the mental health and wellbeing of young LGBTQ people. Our online and offline lives are deeply intertwined, with online connections often allowing us to deepen existing relationships.

The problem is less that young people are online, and more that online life has rushed in to fill the gaps left by a shrinking offline world.

Moreover, digital platforms are built for profit, not development. Young people are shaping their identities, sense of belonging and social status within systems designed to drive constant engagement – a phenomenon which is only accelerating with the advent of AI.

Social media platforms encourage comparison, performance and rapid responses. More broadly, the digital world can pull attention away from the real world and place young people under persistent pressure. It can also affect how – across a formative period of development – they make sense of themselves and the world around them.

Solid foundations in a digital world

There is growing recognition that preventing mental ill health means investing in the social foundations of childhood. McCrory is the chief executive of the mental health charity Anna Freud, which is making a significant shift towards prevention: prioritising building strengths,reducing risks and supporting wellbeing before problems become entrenched. And, of course, positive relationships are the cornerstone of healthy development.

To reverse rising rates of mental ill health, we need to reimagine and invest in the social scaffolding that supports healthy development, ensuring children and young people grow up in socially rich environments. This requires serious investment in youth services, outdoor spaces and community infrastructure.

Schools need more time for play, creativity and extracurricular activities, not just academic performance. Families need support to create shared experiences, from outdoor play to community participation.

Digital platforms are now part of everyday life, but they must complement rather than replace experiences in the physical world. By enriching, not thinning, young people’s social worlds and giving them places and relationships that build trust, foster agency and support connection, we can strengthen the foundations for lifelong wellbeing.

![]()

Eamon McCrory is affiliated with UCL (Professor of Developmental Neuroscience and Psychopathology) and Anna Freud (CEO)

Ritika Chokhani is currently the recipient of a PhD studentship funded by the Wellcome Trust, focusing on similar research areas.

– ref. Young people’s social worlds are ‘thinning’ – here’s how that’s affecting wellbeing – https://theconversation.com/young-peoples-social-worlds-are-thinning-heres-how-thats-affecting-wellbeing-272111