Source: The Conversation – UK – By Duncan Sayer, Professor in Archaeology, University of Lancashire

Four early Anglo-Saxon swords uncovered during a recent archaeological excavation I took part in each tell a story about how weapons were viewed at the time. There was also a striking discovery of a child buried with spear and shield. Was the child an underage fighter? Or were weapons more than mere tools of war to these people?

Weapons are embedded with values. Would, for example, the Jedi knights in the Star Wars franchise have as much nobility if they were armed with knives instead of light sabres? Today, modern armies fight remotely with missiles and drones, or mechanically with guns and armour. Yet in many countries, an officer still has a ceremonial sword, which worn incorrectly might even reveal an imposter.

The excavation, which I carried out with archaeologist Andrew Richardson, focused on an early medieval cemetery and our swords were found in graves. Our team from the University of Lancashire and Isle Heritage has excavated around 40 graves in total. The discovery can be seen in BBC2’s Digging for Britain.

One of the swords we uncovered has a decorated silver pommel (the rear part of the handle) and ring which is fixed to the handle. It is a beautiful, high status 6th century object sheathed in a beaver fur lined scabbard. The other sword has a small silver hilt and wide, ribbed, gilt scabbard mouth – two elements with different artistic styles, from different dates, brought together on one weapon.

This mixture was also seen in the Staffordshire Hoard (discovered in 2009) which featured 78 pommels and 100 hilt collars with a range of dates from the 5th to the 7th centuries AD.

In medieval times, swords – or their parts – were curated by their owners, and old swords were valued more highly than new ones.

The Old English poem Beowulf (probably composed between the 8th and early 11th century) describes old swords (“ealdsweord”), ancient swords (“gomelswyrd”) and heirlooms (“yrfelafe”). As well as describing “waepen wundum heard” – “weapons hardened by wounds”.

There are two sword riddles in the Exeter Book, a large codex of poetry written down in the 10th century (although the texts within it may describe earlier attitudes). In riddle 80, the sword describes itself: “I am a warrior’s shoulder-companion”. It’s an interesting turn of phrase given our 6th century discoveries. In each case the hilt was placed at the shoulder and the arm of the deceased appeared to hug the weapon.

A comparable embrace has been seen in burials at Dover Buckland, also in Kent. There were two in Blacknall Field, Wiltshire, and one in West Garth Gardens, Suffolk. It is, however, unusual to see four people buried like this in one cemetery, and interestingly they were found in close proximity.

The part of the cemetery we have excavated includes several weapon burials placed around a deep grave with a ring ditch enclosing it. A small mound of earth would have been built over the top of the grave marking it out.

This earliest grave – the one that the others weapon graves used to guide their location – contained a man without metal artefacts or weapons. Weapon graves were more popular in the generations either side of the middle 6th century, so it is likely this person was buried before the fashion to dress the dead with weapons was established. Perhaps because during the tumultuous later 5th century and earliest years of the 6th century weapons were valued too highly for the defence of the living.

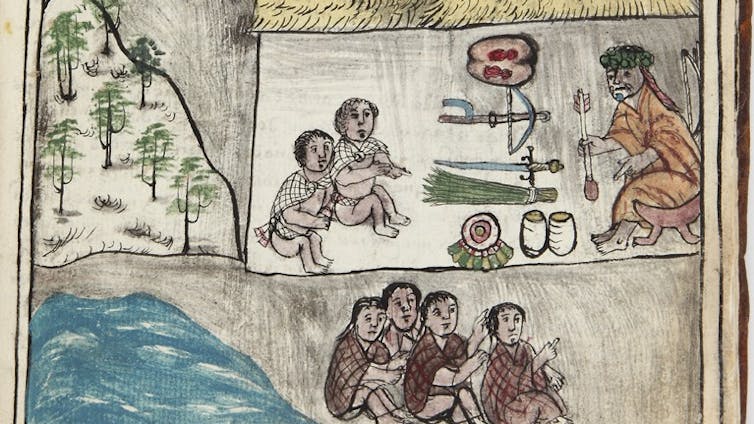

Our further discovery of a 10-12 year old child’s grave with a spear and shield adds to this picture. The child’s curved spine made it unlikely he could use these weapons comfortably.

A second grave of a younger child contained a large silver belt buckle. This looks to have been far too large to be worn by the boy who was just two to three years old. Graves with objects like these usually belong to adult men, large buckles were a symbol of office in later Roman and early Medieval contexts, for example the spectacular gold examples from Sutton Hoo.

So why were these objects found in the graves? Recent DNA results point to the importance of relatedness, particularly within the Y chromosome that denotes male ancestry.

Read more:

Updown girl: DNA research shows ancient Britain was more diverse than we imagined

At West Helsterton in east Yorkshire, DNA results point to a biological relationships between men buried in close proximity. Many of these men had weapons, including one with a sword and two spears. Many of the other male graves were placed around their heavily armed ancestor.

We are not saying that ancient weapons were purely ceremonial. Dents on shields, and wear on bladed weapons speak of practice and conflict. Injury and early death seen in skeletons testifies to the use of weapons in early medieval society and early English poetry speaks of grief and loss as much as heroism.

As Beowulf shows, feelings of loss were bound up in the display of the male dead and their weapons as well as fears for the future:

The Geat people built a pyre for Beowulf, Beowulf’s funeral

stacked and decked it until it stood four-square,

hung with helmets, heavy war-shields

and shining armour, just as he had ordered.

Then his warriors laid him in the middle of it,

mourning a lord far-famed and beloved.

The weapons in our graves were as much as an expression of loss and grief, as they were a physical statement about strength or masculinity and the male family. Even battle hardened and ancient warriors cried, and they buried their dead with weapons like swords that told stories.

The spear, shield and buckles found in little graves spoke of the men these children might have become.

![]()

Duncan Sayer would like to thank Dr Andrew Richardson who is a co-director of the east Kent excavation project.

– ref. Four early medieval swords found in Kent – child graves reveal they were more than just weapons – https://theconversation.com/four-early-medieval-swords-found-in-kent-child-graves-reveal-they-were-more-than-just-weapons-274059