Source: The Conversation – UK – By Martin Farr, Senior Lecturer in Contemporary British History, Newcastle University

Each is the main political subject in their country, and one is the main political subject in the world. Each rode the populist wave in 2016, campaigning for the other. In 2024 the tandem surfers remounted on to an even greater breaker. Yet, though nothing has happened to suggest that bromance is dead, neither Donald Trump nor Nigel Farage publicly now speak of the other.

Trump’s presidential campaign shared personnel with Leave.eu, the unofficial Brexit campaign. Farage was on the stump with Trump, and his “bad boys of Brexit” made their pilgrimage to Trump Tower after its owner’s own triumph in the US election. Each exulted in the other’s success, and what it portended.

Trump duly proposed giving the UK ambassadorship to the United States to Farage. Instead, Farage became not merely MP for Clacton, but leader of the first insurgent party to potentially reset Britain’s electoral calculus since Labour broke through in 1922.

Then, Labour’s challenge was to replace the Liberals as the alternative party of government. It took two years. Reform UK could replace the Conservatives in four.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

Trump, meanwhile, has achieved what in Britain has either been thwarted (Militant and the Labour party in the 1980s) or has at most had temporary, aberrant, success (Momentum and the Labour party in the 2010s): the takeover of a party from within. Farage has been doing so – hitherto – from without.

At one of those historic forks in a road where change is a matter of chance, after Brexit finally took place, Farage considered his own personal leave – to go and break America.

The path had been trodden by Trump-friendly high-profile provocateurs before him: Steve Hilton, from David Cameron’s Downing Street, via cable news, now standing to be governor of California; Piers Morgan, off to CNN to replace the doyen of cable news Larry King, only to crash, but then to burn on, online. Liz Truss, never knowingly understated, has found her safe space – the rightwing speaking circuit.

But Farage remained stateside. He knew his domestic platform was primed more fully to exploit the voter distrust that his nationalist crusade had done so much to provoke.

The Trump effect

Genuine peacetime transatlantic affiliations are rare, usually confined to the leaders of established parties: Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. One consequence of the 2016 political shift is that the US Republicans and the British Conservatives, the latter still at least partially tethered to traditional politics, have become distanced.

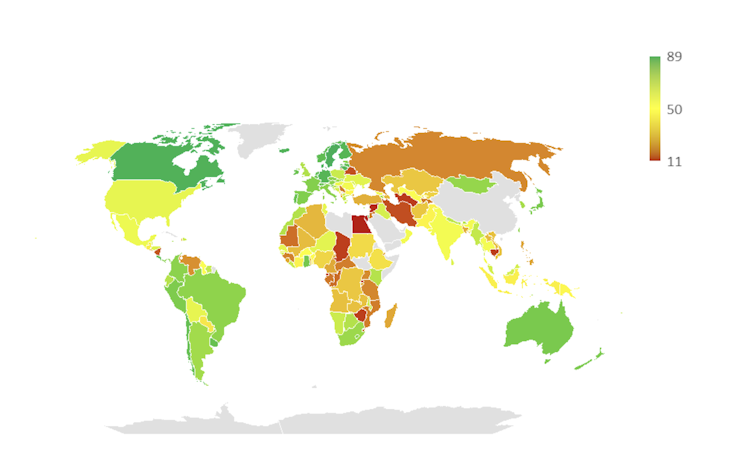

During the first Trump administration, and even in the build up to the second, it was Farage who was seen as the UK’s bridge to the president. But today, at the peak of their influence, for Farage association can only be by inference, friendship with the US president is not – put mildly – of political advantage. For UK voters, Trump is the 19th most popular foreign politician, in between the King of Denmark and Benjamin Netanyahu.

There is, moreover, the “Trump effect”. Measuring this is crude – circumstances differ – but the trend is that elections may be won by openly criticising, rather than associating with, Trump. This was the case for Mark Carney in Canada, Anthony Albanese in Australia, and Nicușor Dan in Romania.

Trump’s second state visit to the UK will certainly be less awkward for Farage than it will be Starmer, the man who willed it. Farage will likely not – and has no reason to – be seen welcoming so divisive a figure.

Starmer has no choice but to, and to do so ostentatiously. It is typical of Starmer’s perfect storm of an administration that he will, in the process, do nothing to appeal to the sliver of British voters partial to Trump while further shredding his reputation with Labour voters. Farage would be well served in taking one of his tactical European sojourns for the duration. Starmer may be tempted too.

Outmanoeuvring the establishment

Reflecting the historic cultural differences of their countries, Trump’s prescription is less state, Farage’s is more. The Farage of 2025 that is. He had been robustly Thatcherite, but has lately embraced socialist interventionism, albeit through a most Thatcherite analysis: “the gap in the market was enormous”.

Reform UK now appears to stand for what Labour – in the mind of many of its voters – ought to. Eyeing the opportunity of smokestack grievances, Farage called for state control of steel production even as Trump was considering quite how high a tariff to put on it. Nationalisation and economic nationalism: associated restoratives for national malaise.

Aggressively heteronormative, Trump and Farage dabble in the natalism burgeoning in both countries – as much a cultural as an economic imperative. Each has mastered – and much more than their adversaries – social media. Each has come to recognise the demerits in publicly appeasing Putin.

And Reform’s rise in a hitherto Farage-resistant Scotland can only endear him further to a president whose Hebridean mother was thought of (in desperation) as potentially his Rosebud by British officials preparing for his first administration.

Given their rhetorical selectivity, Trump and Farage’s rolling pitches are almost unanswerable for convention-confined political opponents and reporters. These two anti-elite elitists continue to confound.

Unprecedentedly, for a former president, Trump ran against the incumbent; Farage will continue to exploit anti-incumbency, despite his party now being in office. Most elementally, the pair are bound for life by their very public near-death experiences. Theirs is, by any conceivable measure, an uncommon association.

Farage’s fleetness of foot would be apparent even without comparison with the leaden steps of the leaders of the legacy parties. His is a genius of opportunism. That’s why he knows not to remind us of his confrere across the water.

![]()

Martin Farr does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Have you noticed that Nigel Farage doesn’t talk about Donald Trump anymore? – https://theconversation.com/have-you-noticed-that-nigel-farage-doesnt-talk-about-donald-trump-anymore-258333