Source: The Conversation – UK – By Jay Silverstein, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Chemistry and Forensics, Nottingham Trent University

ResoluteSupportMedia / Flickr, CC BY-ND

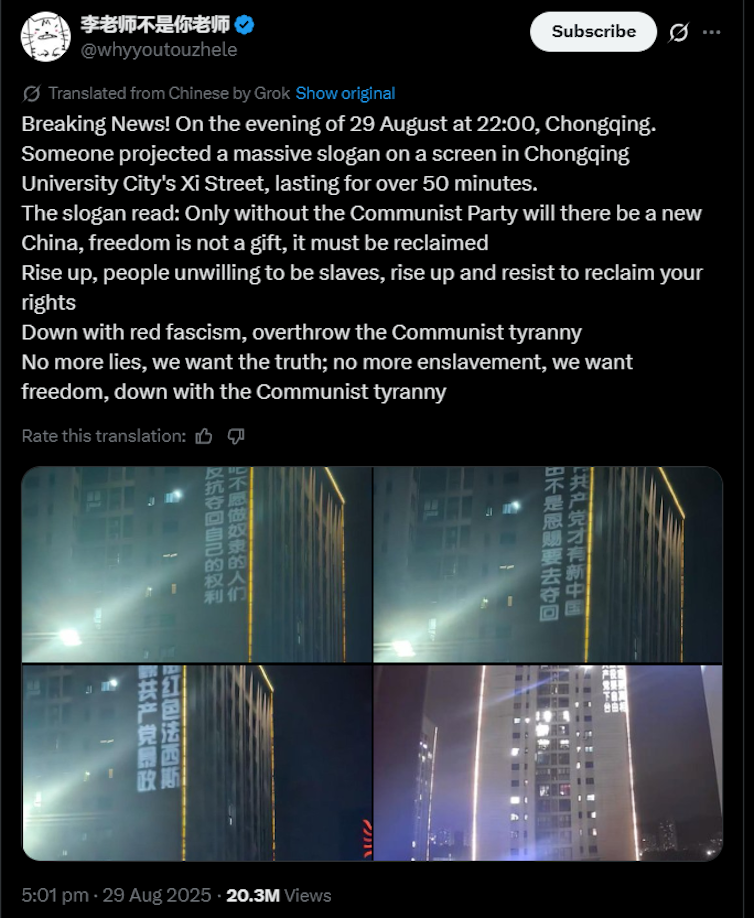

The expectation that competition for dwindling resources drives societies towards conflict has shaped much of the discourse around climate change and warfare. As resources become increasingly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations, climate change is often framed as a trigger for violence.

In one study from 2012, German-American archaeologist Karl Butzer examined the conditions leading to the collapse of ancient states. Among the primary stressors he identified were climate anxieties and food shortages.

States that could not adapt followed a path towards failure. This included pronounced militarisation and increased internal and external warfare. Butzer’s model can be applied to collapsed societies throughout history – and to modern societies in the process of dissolution.

Wars and climate change are inextricably linked. Climate change can increase the likelihood of violent conflict by intensifying resource scarcity and displacement, while conflict itself accelerates environmental damage. This article is part of a series, War on climate, which explores the relationship between climate issues and global conflicts.

Bronze age aridification in Mesopotamia from roughly 2200BC to 2100BC, for example, is correlated with an escalation of violence there and the collapse of the Akkadian empire. Some researchers also attribute drought as a major factor in recent wars in east Africa.

There is a wide consensus that climatic stress contributes to regional escalations of violence when it has an impact on food production. Yet historical evidence reveals a more complex reality. While conflict can arise from resource scarcity and competition, societal responses to environmental stress also depend on other factors – including cultural traditions, technological ingenuity and leadership decisions.

The temptation to draw a direct correlation between climate stress and war is both reductionist and misleading. Such a perspective risks surrendering human agency to a deterministic “law of nature” – a law to which humanity need not subscribe.

Catalysing transformation

In the first half of the 20th century, researchers grappled with the Malthusian dilemma: the fear that population growth would outpace the environment’s carrying capacity. The reality of this dynamic has contributed to the collapse of certain civilisations around the world.

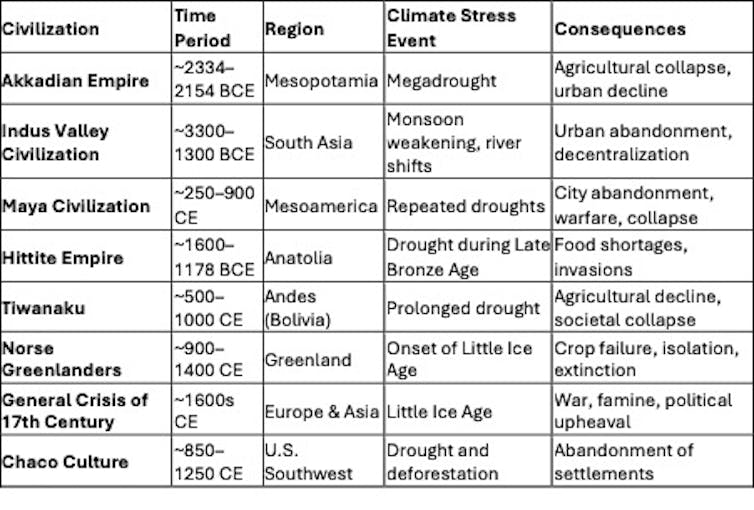

These include the Maya and Indus Valley civilisations in Mesoamerica and south Asia respectively. The same applies to the Hittite in what is now modern-day Turkey and the Chaco Canyon culture in the US south-west.

Civilisations affected by climate stress:

Jay Silverstein, CC BY-NC-ND

However, history is equally rich with examples of societies that have successfully averted crisis through innovation and adaptation. From the dawn of agriculture (10,000BC) onward, human ingenuity has consistently expanded the boundaries of environmental possibility. It has also intensified the means of food production.

Irrigation systems, efficient planting techniques and the selective breeding of crops and livestock enabled early agricultural societies to flourish. In Roman (8th century BC to 5th century AD) and early medieval Europe (5th to 8th centuries AD), the development of iron ploughshares revolutionised soil cultivation. And water-lifting technologies – from the Egyptian shaduf to Chinese water wheels and Persian windmills – expanded arable land and intensified production.

In the 19th century, when Europe’s population surged and natural fertiliser supplies such as guano became strained, the Haber-Bosch process revolutionised agriculture by enabling nitrogen to be extracted from the atmosphere. This allowed Europe to meet its growing demand for food and, incidentally, munitions.

Danish economist Esther Boserup’s work from 1965, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth, challenged the Malthusian orthodoxy. It demonstrated that population pressure can stimulate technological innovation. Boserup’s insights remain profoundly relevant today.

As humanity confronts an escalating environmental crisis driven by global warming, we stand at another historic inflection point. The reflexive response to climate stress – political instability and conflict – should be challenged by a renewed commitment to adaptation, cooperation and innovation.

Baldiri / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

Dwindling military superiority

There are many examples of societies successfully overcoming environmental threats. But our history is also full of failed civilisations that more often than not suffered ecological catastrophe.

In many cases, dwindling resources and the lure of wealth in neighbouring societies contributed to invasion and military confrontation. Droughts have been implicated in militaristic migration in central Asia, such as the westward movement of the Huns and the southward push of the Aryans.

Asymmetries in military power can encourage or deter conflict. They offer opportunities for reward or impose strategic constraints. And while military superiority has largely shielded the wealthiest nations in the modern era, this protection may erode in the foreseeable future.

Natural disasters that erode security infrastructure are becoming increasingly frequent and severe. In 2018, for example, two hurricanes caused a combined US$8.3 billion (£6.2 billion) in damage to two military facilities in the US. There has also been a proliferation of inexpensive military technologies like drones.

Both of these developments could create new opportunities to challenge dominant powers. Under such conditions, increases in military conflict should be expected in the coming decades.

In my view, dramatic action must be taken to avoid a spiral of conflict. Ideals, knowledge and data should be translated into political and economic will. This will require coordinated efforts by every nation.

The growth of organisations such as the Center for Climate and Security, a US-based research institute focused on systemic climate and ecological security risks, signals movement in the right direction. Yet such organisations face a steep climb in their efforts to translate geopolitical climate issues into meaningful political action.

One of the main barriers is the rise of anti-intellectualism and populist politics. Often aligned with unregulated capitalism, this can undermine the very strategies needed to address the unfolding crisis.

If we are to avoid human tragedy, we will need to transform our worldview. This requires educating those unaware of the causes and consequences of global warming. It also means holding accountable those whose greed and lust for power have made them adversaries of life on Earth.

History tells us that environmental stress need not lead to war. It can instead catalyse transformation. The path forward lies not in fatalism, but in harnessing the full spectrum of human creativity and resilience.

![]()

Jay Silverstein does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Environmental pressures need not always spark conflict – lessons from history show how crisis can be avoided – https://theconversation.com/environmental-pressures-need-not-always-spark-conflict-lessons-from-history-show-how-crisis-can-be-avoided-262300