Source: The Conversation – UK – By Rebecca A. Drummond, Professor, Immunology and Immunotherapy, University of Birmingham

The “gut microbiome” has become a popular health term in recent years. It’s easy to see why, with an abundance of research showing how important the trillions of microbes living in our gut are for health.

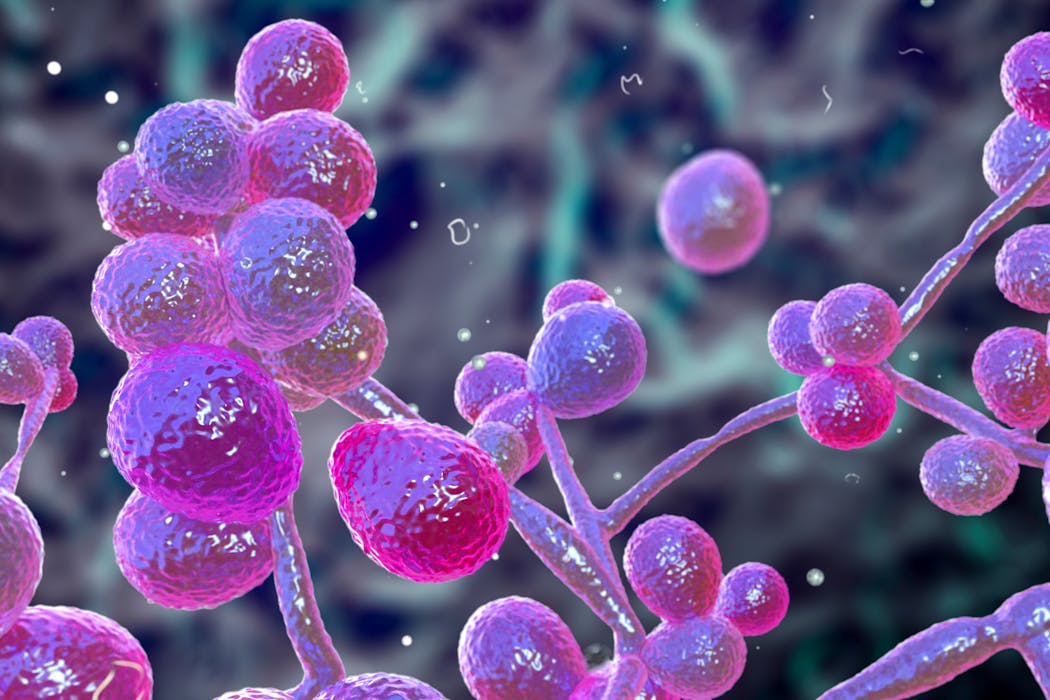

But what many people might not realise is that the microbiome doesn’t only contain bacteria. It also contains other types of microbes – including fungi. The fungal component of the microbiome is called the “mycobiome”.

Although the mycobiome has been less well studied than its bacterial counterpart, recent research shows it’s sensitive to diet and may affect our health, too.

The best studied mycobiome is the one in our intestines. It’s composed of many fungal species. The most common fungal species found there, particularly in the Western world, belong to the Candida family.

Candida are a type of yeast. For most of us, the Candida population in our mycobiome is kept in check by our immune system and our gut bacteria. But changes to either of these can cause populations of Candida to expand in the mycobiome. This can be a problem, because Candida may cause life-threatening infections in people with damaged immune systems.

For example, research found that hospital patients who are given antibiotics are more likely to develop Candida infections.

This is partly explained by the effect of antibiotics, which kill off certain species of gut bacteria that compete with Candida for space and resources within the intestine. Antibiotics have also been found to directly alter our immune cells and how they fight fungal infections.

Another study, which analysed the mycobiome of cancer patients, found that those who developed serious Candida infections had an overgrowth of the fungus in their mycobiome just before the infection started. Combined with the damaging effects of chemotherapy on the immune system, this made it harder for patients to fight off the infection.

Disruption in the mycobiome’s Candida balance has also been linked to several other diseases. For instance, Candida levels are high in patients who are critically ill. This suggests that too much Candida in our guts is a sign of poor health.

Changes in the fungal mycobiome have also been linked to several gut diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease. Research on Crohn’s disease has also shown that patients have an overgrowth of Candida. These fungi also produce toxins that irritate the gut lining, which could potentially explain some of the symptoms Crohn’s patients experience.

High levels of Candida in the gut can activate immune cells as well, making them more inflammatory. This has been seen in patients with severe COVID-19.

Mycobiomes in the body

The mycobiome isn’t only found in our gut.

We also have a skin mycobiome. In fact, the skin between our toes contains a more diverse number of fungal species than any other skin mycobiome.

The skin mycobiome is mostly dominated by a fungus called Malassezia. This yeast has adapted to grow on the skin’s surface.

Malassezia can activate the immune cells that reside between the skin’s layers. This may lead to inflammation linked to skin disorders, such as psoriasis and eczema.

Ternavskaia Olga Alibec/ Shutterstock

Candida auris is also a cause for concern. This fungus is resistant to many antifungal drugs, which is why it can be a problem if it grows on the skin’s surface. In a hospital or emergency room, this could be dangerous – particularly to patients who have immune system problems.

Women also have a mycobiome within the vagina. Its balance with the bacterial communities living there can be a big determinant for vaginal health.

One of the most common fungal infections globally is vaginal candidiasis (thrush). It can cause symptoms such as intense itching, pain and swelling. Many adult women will experience at least one thrush infection in their lifetime.

The source of thrush is another fungus from the Candida family: Candida albicans. This is a common member of the vaginal mycobiome.

The vagina’s microbiome is normally dominated by the bacteria Lactobacillus which help keep Candida populations in check. But if the balance between bacteria and fungi gets disrupted (for example, by antibiotics), the fungus can overgrow or produce inflammatory molecules within the vagina. This inflammatory response is responsible for common thrush symptoms such as redness and itching.

Probiotics may help to restore the balance between fungi and bacteria to prevent vaginal yeast infections – although this has had limited success so far. Some new treatments that target inflammation-causing fungal molecules have shown promise in animal models and in small numbers of women.

There’s good evidence to suggest we might also have a mycobiome in the lungs and in breastmilk.

Controversially, some have even suggested that we may have small numbers of fungal cells in the brain – and these fungal cells may be linked with neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinsons and Alzheimer’s.

Autopsy studies have found evidence of fungi in the brains of people who died from brain disorders – but this doesn’t prove the fungi caused their illness or that it was there during their life.

Experimental studies in mice have also shown that small numbers of fungal cells can survive in the brain for long periods of time – and the presence of these fungal cells was linked with reduced memory function.

Experiments in flies have also shown fungi may travel to the brain and affect function. This is the best evidence we currently have showing small numbers of fungi may get into the brain and survive long-term.

Whether this occurs in people, and if this would be considered a true mycobiome, remains to be proven.

There’s still much we don’t know about the mycobiome. But with continued research in this area we may soon better understand the mycobiome’s importance in our health and how we can nurture and care for it.

![]()

Rebecca A. Drummond receives funding from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the Lister Institute for Preventative Medicine.

– ref. The fungi living in the body play an important role in health – here’s what you should know about the ‘mycobiome’ – https://theconversation.com/the-fungi-living-in-the-body-play-an-important-role-in-health-heres-what-you-should-know-about-the-mycobiome-264545