Source: The Conversation – UK – By Matthew Barnfield, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Politics and International Relations, Queen Mary University of London

Whatever the Labour government is doing, it doesn’t seem to be working, yet. Economic growth – its number one priority – hasn’t taken off. The party is trailing far behind Reform in the polls. It risks presiding over an outright decrease in living standards.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer responds to criticism by reminding us that, from the outset, he has been clear that short-term pain is needed in order to secure long-term gain. He recently repeated this message in his speech to the Labour party conference, proclaiming: “Our path, the path of renewal, it’s long, it’s difficult, it requires decisions that are not cost-free or easy.”

The trouble with this politics of patience is that, funnily enough, many voters care a lot about how things go in the short term. And recent polling data suggests a failure to make improvements in the near term could drive Labour supporters to other parties at the next election – especially those voters who focus more on the short term.

Some admittedly important immediate improvements have been delivered since Labour came to power in 2024. These include public sector pay rises and overall wage growth. But without more meaningful change, including on measures that could make a big difference on living standards, rather than “short-term pain, long-term gain”, what some people might think they are really getting is “all pain, no gain”.

Tackling child poverty is a case in point: a promised strategy from the government did not appear in its first year in office, despite the urgency of the problem.

Polling data I recently collected with my colleagues Philip Cowley and Karl Pike, as part of our ongoing research into short- and long-term policymaking, reveals that the patience this government expects from the British public might be incurring a major electoral cost. Those of its 2024 voters who focus more on the short term in their political thinking are more likely to intend to vote for a different party at the next election.

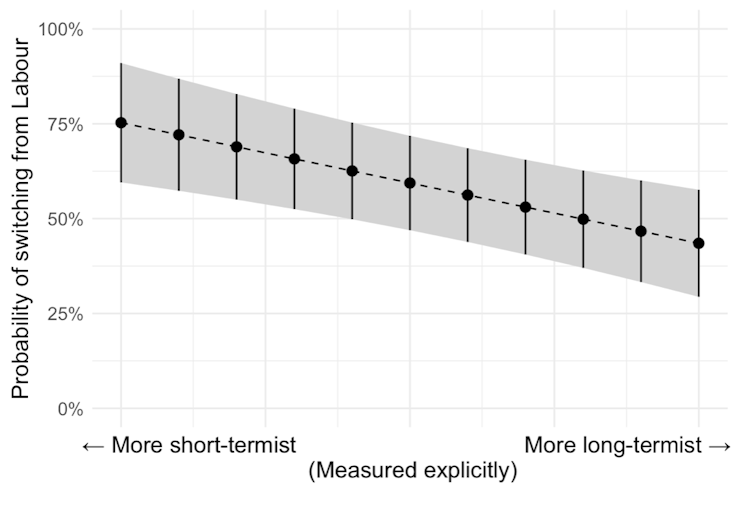

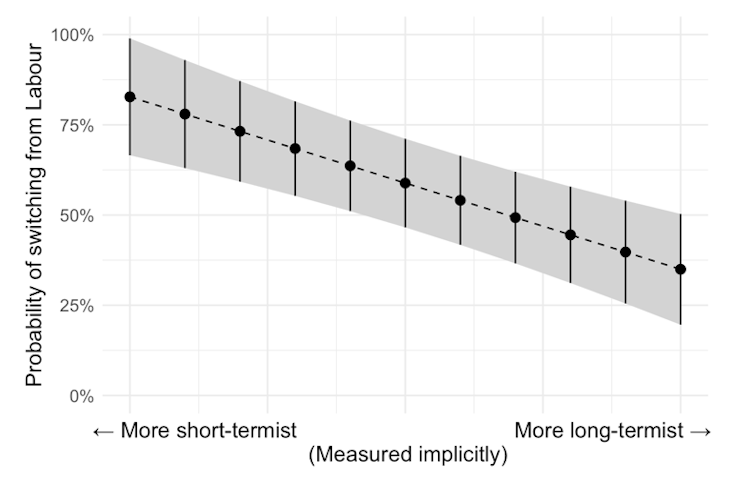

We tested whether people were short-termists or long-termists by explicitly asking whether they focused on the short or long term when they voted. We also tested this more implicitly by asking a series of other less direct questions about what psychologists call “future orientation”.

We found slightly over a third of Labour voters were more short-termist than long-termist. And the more focused on the short term our participants said they were, the more likely they were to indicate they would vote for a different party in the next election, not vote at all or are not sure how they will vote – that is, do anything other than vote for Labour again next time around.

This ranged from those with the most short-term views having around a 75% chance of saying they would abandon Labour, to those who saw themselves as the most long-termist having a 43% chance.

Self-declared short and long-term thinkers:

M Barnfield/P Cowley/K Pike, CC BY-ND

Similar results were in evidence for the implicit measures. According to our model, of the most short-termist, Labour are losing around 83%. Of the most long-termist, they are losing just 35%. In each case, the differences are so great that we can be sure the overall effect is not purely down to chance.

All these probabilities (and margins of error) come from statistical models where we account for people’s age, gender, ethnicity and left-right political views, ruling those other factors out as explanations of what we find.

Implicitly measured short and long-term thinkers

M Barnfield/P Cowley/K Pike, CC BY-ND

We also asked respondents whether they think the UK is heading in the right or wrong direction. In line with polling in recent years, a huge 70% of our sample says the country is (still) heading in the wrong direction. Only 15% said it is heading in the right direction.

But we found that those voters who focus more on the short term are much more likely than long-termist people to think the country is heading in the wrong direction. A shortage of short-term wins makes it hard to see how the country can be on the right track.

What’s more, of Labour’s 2024 voters, those who think the UK is heading in the wrong direction have about a 74% chance of switching to another party in 2029. But only around 28% of 2024 Labour voters who think the country is heading in the right direction intend to vote for a different party.

The government is right that meaningful change, or “fixing the foundations” of the country, does not happen overnight. But equally if change takes as long as Keir Starmer says, a year into his government it should soon be getting underway.

For the politics of patience to be persuasive, especially to the short-termist voters the party is losing at an alarming rate, a positive trajectory must become clear soon. Otherwise, Labour might not remain in power long enough to secure the gains it is promising in return for patience.

The government should not give up on its long-term missions, but seeing out its “decade of national renewal” by winning the next election will require more obvious short-term change, too.

![]()

Matthew Barnfield receives funding from the British Academy.

– ref. Keir Starmer needs to give voters short-term gain to persuade them he can deliver long-term renewal – https://theconversation.com/keir-starmer-needs-to-give-voters-short-term-gain-to-persuade-them-he-can-deliver-long-term-renewal-267404