Source: The Conversation – UK – By Damian Bailey, Professor of Physiology and Biochemistry, University of South Wales

On January 14 2004, the United States announced a new “Vision for Space Exploration”, promising that humans would not only visit space but live there. Two decades later, Nasa’s Artemis programme is preparing to return astronauts to the Moon and, eventually, send humans to Mars.

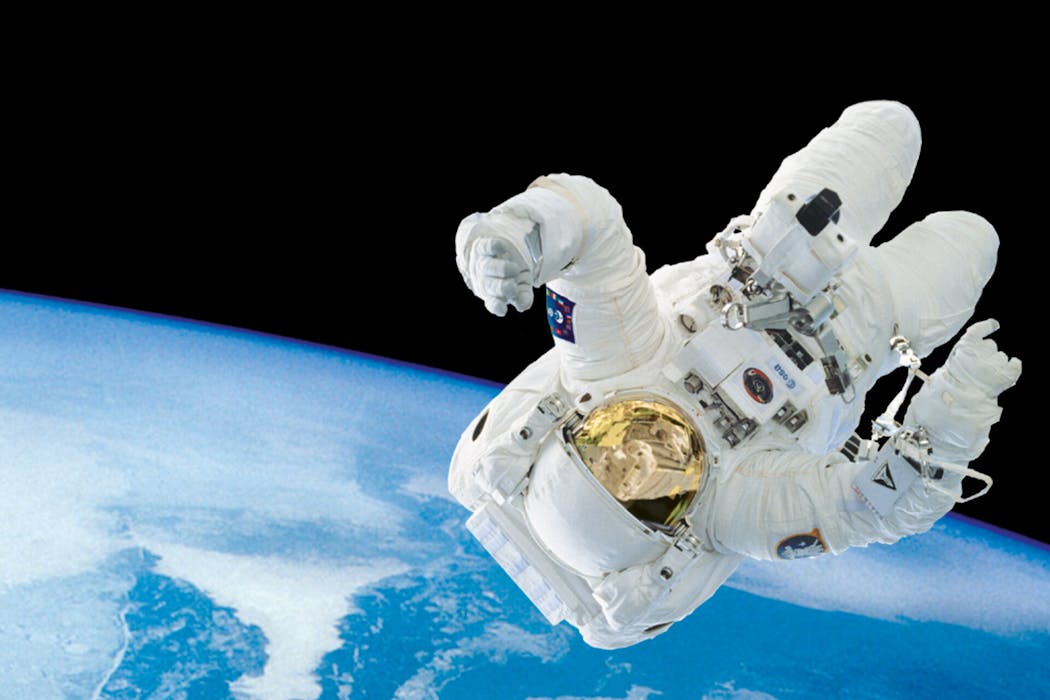

That mission will last around three years and cover hundreds of millions of kilometres. The crew will face radiation, isolation, weightlessness and confinement, creating stresses unlike any encountered by astronauts before. For physiologists, this is the ultimate frontier: a living laboratory where the human body is pushed to, and sometimes beyond, its biological limits.

Space is brutally unforgiving. It is a vacuum flooded with radiation and violent temperature extremes, where the absence of gravity dismantles the systems that evolved to keep us alive on Earth. Human physiology is tuned to one atmosphere of pressure, one gravity and one fragile ecological niche. Step outside that narrow comfort zone and the body begins to fail.

Yet adversity drives discovery. High-altitude research revealed how blood preserves oxygen at the edge of survival. Deep-sea and polar expeditions showed how humans endure crushing pressure and extreme cold. Spaceflight continues that tradition, redefining our understanding of life’s limits and showing how far biology can bend without breaking.

To understand these limits, physiologists are mapping the “space exposome” – everything in space that stresses the human body, from radiation and weightlessness to disrupted sleep and isolation. Each factor is harmful on its own, but combined they amplify one another, pushing the body to its limits and revealing how it truly works.

Read more:

What happens to the brain in zero gravity?

From this complexity emerges what scientists call the “space integrome”: the complete network of physiological connections that keeps an astronaut alive in the most extreme environment known.

When bones lose minerals, the kidneys respond. When fluid shifts toward the head, it changes pressure in the brain and affects vision, brain structure and function. Immune cells react to stress hormones released by the brain. Every system influences the others in a continuous biological feedback loop.

The body as a biosphere

The spacesuit is the most tangible symbol of this integration. It is a wearable biosphere: a miniature, self-contained environment that keeps the person inside it alive, much as Earth’s atmosphere does for all life. The suit shields the body from the lethal physics of space, protecting against vacuum, radiation and extreme temperatures.

Inside its layered shells of mylar (a reflective plastic that insulates against heat), kevlar (a strong fibre that resists impact) and dacron (a tough polyester that maintains shape and pressure), astronauts live in delicate balance. There is just enough internal pressure to stop their bodily fluids from boiling in a vacuum, yet still enough flexibility to move and work.

Read more:

Modern spacesuits have a compatibility problem. Astronauts’ lives depend on fixing it

Every design choice mirrors a physiological trade-off. At too low pressure, consciousness fades within seconds. At too high pressure, the astronaut becomes trapped in a rigid shell.

Radiation remains spaceflight’s most insidious hazard. Galactic cosmic rays, made up of high-energy protons and heavy ions, slice through cells and fracture DNA in ways that biology on Earth was never built to repair. Exposure to these rays can cause DNA damage and chromosomal rearrangements that raise the risk of cancer.

But research into radiation biomarkers – molecular signals that show how cells respond to radiation exposure – is not only improving astronaut safety, it is also helping transform cancer treatment on Earth. The same biological markers that reveal radiation damage in space are being used to refine radiotherapy, allowing doctors to measure tissue sensitivity, personalise doses and limit damage to healthy cells.

Studies on how cells repair DNA after exposure to cosmic radiation are also informing the development of new drugs that protect patients during cancer treatment.

Microgravity presents another paradox. In orbit, astronauts lose 1–1.5% of their bone mass each month, and muscles weaken despite daily exercise. But this extreme environment also makes space an unparalleled model for accelerated ageing. Studies of bone loss and muscle atrophy in microgravity are helping uncover molecular pathways that could slow degenerative disease and frailty back home.

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station spend more than two hours a day performing “countermeasures”: intensive resistance workouts and sessions in lower-body negative pressure chambers, which draw blood back towards the legs to maintain healthy circulation.

They also eat carefully planned diets to stabilise their metabolism. No single strategy is enough, but together these help keep human biology closer to balance in an environment defined by instability.

Digital physiology

Tiny sensors embedded in spacesuits, or even placed under the skin, can now track heart rate, brain activity and chemical changes in the blood in real time. Multi-omic profiling combines information from across biology (genes, proteins and metabolism) to build a complete picture of how the body responds to spaceflight.

This data feeds into digital twins: virtual versions of each astronaut that allow scientists to simulate how their body will react to stressors such as radiation or microgravity.

The astronaut of the future will not simply endure space. They will work with their own biology, using real-time data and predictive algorithms to spot risks before they happen – adjusting their environment, exercise or nutrition to keep their body in balance.

By studying how humans survive without gravity, we are also learning how to live better with it. Space physiology has already helped shape treatments for osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease, and it is improving our understanding of age-related muscle loss.

Research into spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome – a condition in which fluid shifts in microgravity cause pressure to build inside the skull, sometimes leading to vision changes – is helping scientists understand intracranial hypertension on Earth.

Even studies of isolation and resilience in astronauts have advanced research into mental health and stress adaptation, offering insights that proved invaluable during the COVID-19 pandemic, when millions faced confinement and social separation similar to life aboard a spacecraft.

Ultimately, Mars will test our biology more than our technology. Every gram of muscle preserved, every synapse protected, every cell repaired will be a triumph of physiology. Space may dismantle the human body, but it also reveals our body’s astonishing capacity to rebuild.

![]()

Damian Bailey is supported by grants from the European Space Agency, SpaceX and Royal Society Wolfson Research Fellowship. He is Editor-in-Chief of Experimental Physiology and outgoing Chair of the Life Sciences Working Group and outgoing member of the Human Spaceflight and Exploration Science Advisory Committee to ESA. He is also a current member of the ESA-HRE-Biology Panel and Space Exploration Advisory Committees to the UK and Swedish National Space Agencies, and consultant to Bexorg, Inc. (Yale, USA) focused on the technological development of novel biomarkers of cerebral bioenergetic function in humans.

Angelique Van Ombergen works as Chief Exploration Scientist for the Directorate of Human and Robotic Exploration at the European Space Agency. She is an Associate Editor of NPJ Microgravity.

– ref. Mission to Mars: how space exploration pushes the human body to its limits – https://theconversation.com/mission-to-mars-how-space-exploration-pushes-the-human-body-to-its-limits-267837