Source: The Conversation – UK – By Sean Brophy, Senior Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan Business School, Manchester Metropolitan University

In the upcoming budget, Chancellor Rachel Reeves is expected to raise the minimum wage to £12.70 an hour: £26,416 annually for a full-time job. This means that the gap between salaries for minimum wage jobs and those for professional jobs that require a degree is shrinking fast.

Some smaller law firms are already paying newly qualified solicitors barely more than minimum wage. “Why would young people take on £45,000 of student debt if they can earn the same stacking shelves?” one executive told the Financial Times.

The concern from business leaders is understandable, but it’s focused on the wrong problem. This isn’t a story about university losing its value. It’s a story about Britain becoming a lower wage economy.

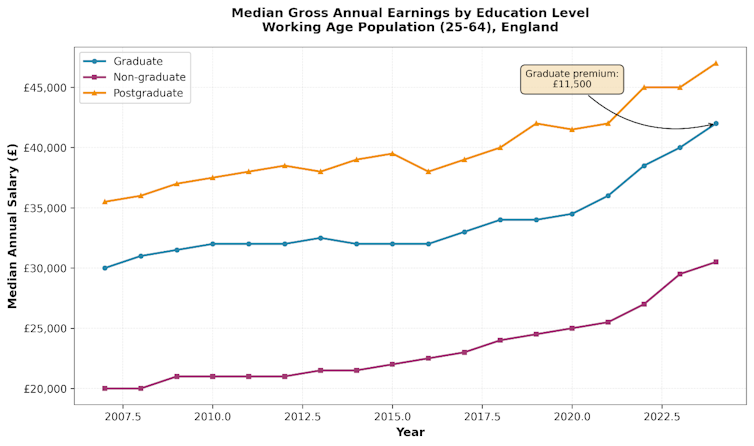

Based on all available evidence, university remains a sound long-term investment. The raw undergraduate earnings premium – the simple difference between graduate and non-graduate median salaries – stands at £11,500 per annum.

Earnings by education level:

Sean Brophy/Office for National Statistics’ Labour Force Survey, CC BY-NC-ND

Earnings typically accelerate as graduates progress through their careers and gain labour market experience. The lifetime earnings premium – the additional amount graduates earn over their working lives compared to non-graduates – remains substantial. The most comprehensive recent analysis estimates that the average UK graduate earns about 20% more in net lifetime earnings than a comparable non-graduate – equivalent to roughly £130,000 for men and £100,000 for women after taxes and student loan repayments.

The issue isn’t whether university pays off. It’s that in the current UK economy, everything pays off less.

It bears emphasising here that investing in education remains the primary mechanism an individual has to improve their life chances. In other words, the problem is structural and not the fault of recent graduates.

Britain’s lower wage trajectory

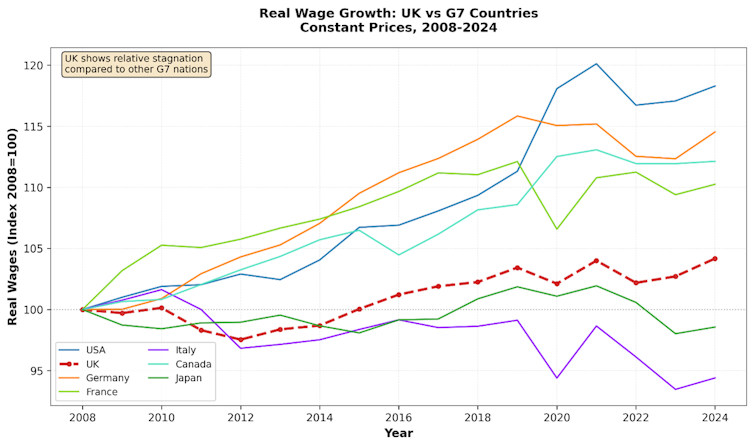

Britain is undergoing a fundamental shift in its economic position relative to competitor nations. It’s transitioning from a top-tier wage economy to a mid-tier one.

The compression of graduate starting salaries against the minimum wage is merely a symptom of this broader downward trend. Since the 2008 financial crisis, UK wage growth has stagnated compared to other advanced economies.

Wage growth in G7 countries, 2008-2024:

Sean Brophy/OECD Data Explorer, Average annual wages, US dollars, PPP converted, CC BY-NC-ND

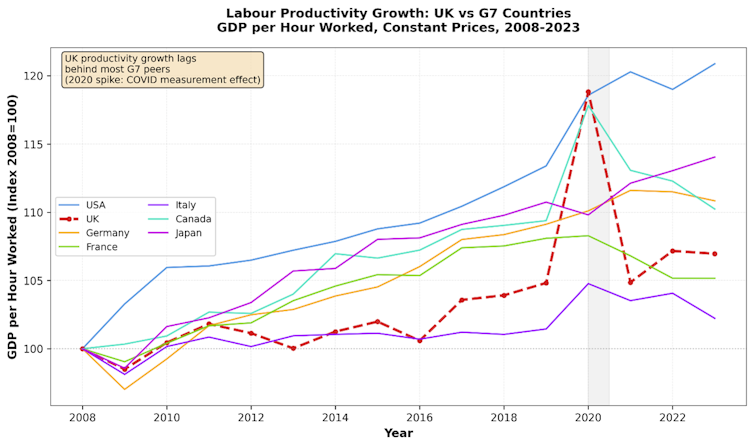

Much has been written about Britain’s so-called “productivity puzzle”, but one of the likely culprits is the fact that British executives don’t invest in training their workers compared to their international competitors. Instead the burden of upskilling the UK workforce shifts to universities.

This in turn causes the government to apply pressure to the higher education sector to be more responsive to the needs of employers, which has the perverse effect of calling for the elimination of what are deemed “low value degrees”.

Yet universities are several steps removed from the day-to-day realities of the workplace, and are far less suited to providing role-specific training than employers themselves.

When neither employers nor universities effectively address the skills needed in the economy, the result contributes to a low-investment, low-productivity trap that depresses wages across the entire economy.

The productivity gap:

Sean Brophy/OECD Data Explorer, CC BY-NC-ND

Until private sector leaders tackle it through renewed training investment, blaming recent graduates or universities for wage compression is misplaced.

Wage compression affects everyone, but it’s particularly visible at the graduate entry level. When the overall wage distribution compresses, entry-level professional salaries get squeezed from below by rising minimum wages and from above by stagnant mid-career earnings.

Risk and reward

The average English graduate now carries £53,000 in student debt. In a high-wage-growth economy, taking on substantial debt to access the graduate premium makes clear sense – you’re buying a ticket to rapid salary progression. In a low-growth economy, the same debt represents a different risk profile for the same investment.

And the social mobility implications are real. Students from families who can afford to subsidise them through university and early career years face less risk than those who cannot.

The fundamental calculus that favours university education hasn’t changed. Educated workers still earn more, enjoy better employment prospects, and have more career options. But the simple fact is that financial returns may be lower in a lower wage economy.

This is similar to how investors adjust expectations after decades of high returns. The question isn’t whether to invest in university, but what financial returns to reasonably expect. A graduate premium of 15% instead of 20% is still a premium. Reaching peak earnings in your early 50s instead of mid 40s is slower, but the trajectory still leads upward.

Britain is settling into a mid-tier wage economy unless firms start investing in workers like their international competitors do. This creates a risk of brain drain, as graduates seek higher wages in countries that value their skills more highly.

Until that changes, universities are urged to scrap “low-value” degrees while employers slash training and expect graduates to bring the skills they no longer provide through training. The graduate premium still exists – but in a lower wage economy, expect it to be smaller.

![]()

Sean Brophy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. University still pays off – even in lower-wage Britain – https://theconversation.com/university-still-pays-off-even-in-lower-wage-britain-268959