Source: The Conversation – UK – By Adam Taylor, Professor of Anatomy, Lancaster University

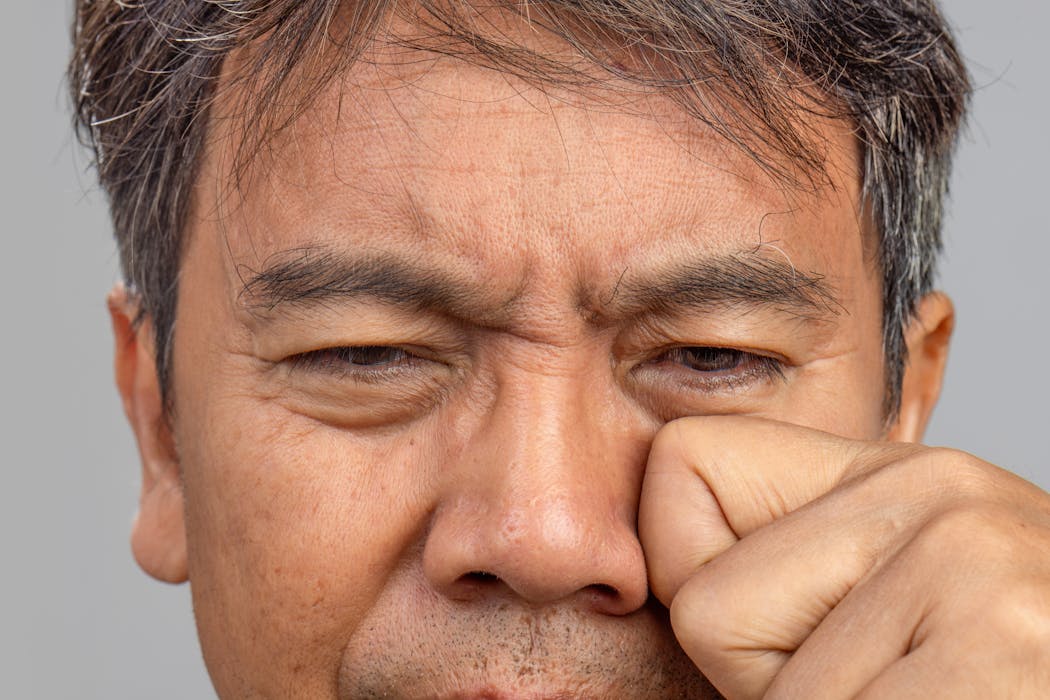

You’re relaxing on the sofa when suddenly your eyelid starts twitching. Or perhaps it’s a muscle in your arm, your leg, or your foot that begins to spasm – sometimes for a few seconds, sometimes for hours or even days. It’s an unsettling sensation that affects about 70% of people at some point in their lives.

Muscle twitches fall into two main types. There’s myoclonus, where a whole muscle or group of muscles twitch or spasm. Then there’s fasciculation, where single muscle fibres twitch – often too weak to move a limb but visible or sensed beneath the skin.

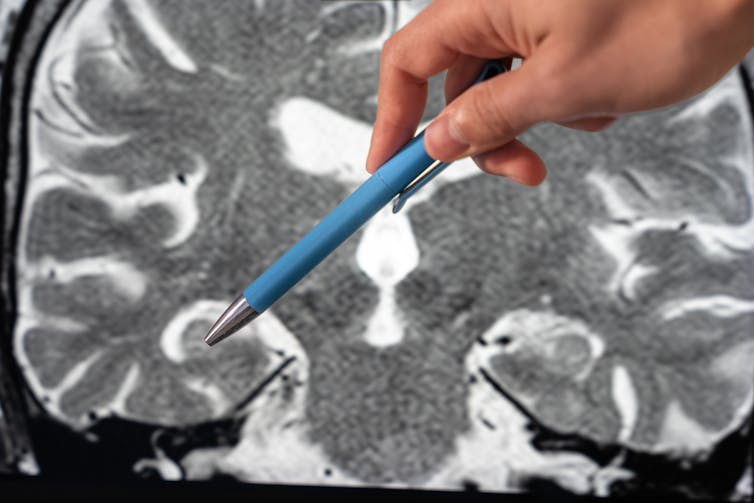

Many factors can trigger both types of twitching, but people often fear the worst. Some fear it could signal multiple sclerosis – a condition that requires extensive testing, including a lumbar puncture to look for inflammation and MRI scans to detect brain changes.

For many people, however, twitching is simply an annoyance. Once doctors rule out serious causes, everyday features of modern life often turn out to be the trigger.

Too much caffeine, for instance, can cause muscle twitching. As a stimulant, it affects both skeletal and cardiac muscle, increasing heart rate and having a similar effect on skeletal muscle in areas such as the arms and legs. It slows down the time it takes for muscles to relax and increases the amount of calcium ions released within muscles, disrupting normal muscle contraction patterns.

Other stimulants such as nicotine, cocaine and amphetamines can cause similar muscular twitching. These substances interfere with the neurotransmitters that control or influence muscle function.

Some prescription medications can also trigger twitching. Antidepressants and anti-seizure drugs, blood pressure medicines, antibiotics and anaesthetics can all cause muscular side-effects.

When minerals run low

Twitching isn’t only caused by what you consume, it can also stem from what your body lacks. Hypocalcaemia, a drop in the amount of calcium in the body, is associated with twitching, particularly in the back and legs.

Calcium is fundamentally important in helping muscle cells rest and remain stable between contractions. When calcium levels fall, sodium channels open more easily. Sodium floods in and, as a result, nerves become hyperactive and muscles contract when they shouldn’t.

There are recognised twitching areas associated with hypocalcaemia, including the Chvostek sign, which is seen in the face and can be triggered by tapping the skin of the cheek just in front of the ear.

Magnesium deficiency can also cause muscle twitching. Some causes of magnesium deficiency are a poor diet or poor absorption in the gut, usually due to conditions such as coeliac disease or other gastrointestinal conditions.

Some medications, particularly when taken over a long period, can cause a drop in magnesium levels in the body. Proton pump inhibitors used to treat reflux and stomach ulcers are recognised for this effect.

Low potassium is another mineral that can cause muscle twitching. Potassium helps muscle cells rest. It’s usually at high levels inside the cell and lower outside, but when potassium levels outside the cell fall, the electrical balance shifts, making muscle cells unstable and prone to misfiring, causing muscle spasms.

If you have no underlying gastrointestinal conditions, eating a healthy, balanced diet is usually enough to ensure you have enough of each of these minerals for normal muscle function.

A healthy water intake is important too, as dehydration affects the balance of sodium and potassium, resulting in abnormal muscle function, such as twitching and spasms. This is even more important during exercise, where overexertion can cause the same phenomenon.

The brain plays a role as well. Stress and anxiety can cause muscles to twitch as a result of overstimulation of the nervous system by hormones and neurotransmitters such as adrenaline.

Adrenaline increases the “alertness” of the nervous system, meaning it’s ready to trigger muscle contraction. It also increases the amount of blood flow and changes the tension of the muscles, which when a surge of energy arrives – or if the muscle is held in suspense for long periods – can result in twitching.

Adrenaline can also result in the nervous system responding to altered levels of neurotransmitters, causing muscle movement when the body is actually at rest.

Infectious agents can cause muscle twitching and spasms, too. The most commonly known is probably tetanus, which causes a phenomenon called lockjaw, where the neck and jaw muscles contract to the point where it becomes difficult to open the mouth and swallow. Lyme disease, from ticks, can also cause muscle spasms.

Many different infections can affect either the nerves or the muscles and can lead to twitching. Cysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, influenza, HIV and herpes simplex have all been linked to muscle twitching.

When doctors rule out these causes, some people receive a diagnosis of benign fasciculation syndrome – involuntary muscle twitching with no identifiable underlying disease.

It’s unknown how common it is, but it’s believed to affect at least 1% of the healthy population. It can persist for months or years, and for many, although benign, it doesn’t resolve completely.

For many people, muscle twitches remain a manageable annoyance rather than a sign of disease. But for others, a healthcare professional may need to rule out more serious causes.

![]()

Adam Taylor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Muscle twitches: why they happen and what they mean – https://theconversation.com/muscle-twitches-why-they-happen-and-what-they-mean-269556