Source: The Conversation – France (in French) – By Marie Hrabanski, chercheuse en sociologie politique, politiques internationales et nationales de l’adaptation de l’agriculture au changement cliamtique, Cirad

À l’échelle mondiale, les systèmes agricoles, alimentaires et forestiers produisent plus du tiers des émissions de gaz à effet de serre, contribuant ainsi au changement climatique de façon significative. Pourtant, l’agriculture n’a été intégrée que tardivement aux négociations des COP sur le climat. Entre enjeux d’adaptation, d’atténuation et de sécurité alimentaire, les avancées restent timides. De récentes initiatives essaient toutefois de mieux intégrer les systèmes agricoles et alimentaires à l’agenda climatique mondial.

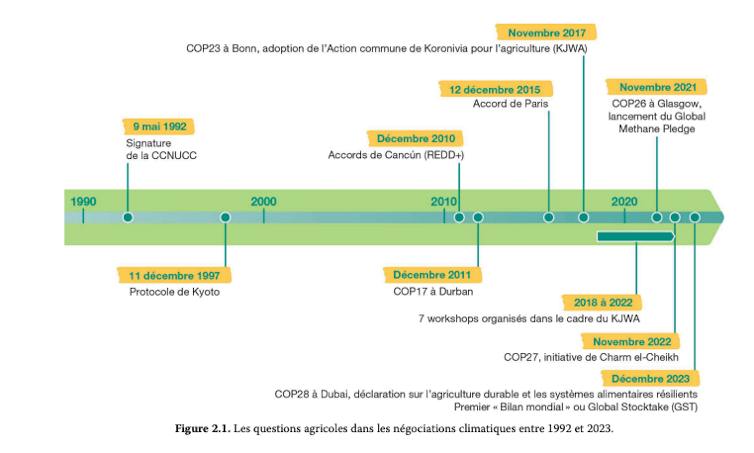

Nous reproduisons ci-dessous la première partie consacrée à ces questions du chapitre 2 (« De 1992 à 2022, la difficile mise à l’agenda de l’agriculture dans les négociations sur le climat ») de _l’Agriculture et les systèmes alimentaires du monde face au changement climatique. Enjeux pour les Suds, publié en juin 2025 par les éditions Quae, sous la coordination scientifique de Vincent Blanfort, Julien Demenois et Marie Hrabanski (librement accessible en e-book).

Depuis 1992 et la signature de la Convention-cadre des Nations unies sur les changements climatiques (CCNUCC), les gouvernements ou parties se rassemblent chaque année au sein des Conférences des parties (COP) pour orienter et opérationnaliser les engagements des États face au changement climatique.

L’agriculture a longtemps été absente de ces négociations qui, jusqu’à la fin des années 1990, se sont focalisées sur l’atténuation des émissions de gaz à effet de serre (GES). Pourtant, les systèmes agricoles et alimentaires sont particulièrement émetteurs de GES, et à la fois « victimes » et « solutions » face au changement climatique.

À partir des années 2010, les questions agricoles puis alimentaires intègrent progressivement l’agenda international du climat. Les États sont chargés de mettre en œuvre les actions climatiques pour l’agriculture et l’alimentation, qui sont détaillées dans leurs engagements climatiques nationaux que sont les contributions déterminées au niveau national (CDN ou NDC en anglais).

En 2020, plus de 90 % de ces contributions nationalement déterminées incluaient l’adaptation au changement climatique et faisaient de l’agriculture un secteur prioritaire, et environ 80 % d’entre elles identifiaient des objectifs d’atténuation du changement climatique dans le secteur agricole.[…]

Les insuffisances du protocole de Kyoto

Les articles 2 et 4 de la convention (CCNUCC) adoptée en 1992 évoquent le lien entre les changements climatiques et l’agriculture. Toutefois, les enjeux sont focalisés sur l’atténuation, par le biais notamment des négociations sur le cadre REDD+ (réduction des émissions dues à la déforestation et à la dégradation des forêts), qui ont abouti en 2013 à Varsovie après plusieurs années de discussions très laborieuses et clivantes, notamment entre pays développés et pays en développement.

À lire aussi :

Crédits carbone et déforestation évitée : impact réel ou risque de greenwashing ?

Le protocole de Kyoto, adopté en 1997, fait référence à l’agriculture et aux forêts, en soulignant que le secteur de l’utilisation des terres, du changement d’affectation des terres et de la foresterie (UTCATF) peut constituer une source de GES.

Ce protocole fixait des objectifs ambitieux de réduction des émissions uniquement pour les pays industrialisés (dits « annexe I »), dans un fonctionnement top-down, contrairement à l’accord de Paris. Il couvrait le méthane et le protoxyde d’azote, principaux gaz émis par le secteur agricole, et établissait des niveaux de référence forestiers à respecter.

Ce mode de travail a toutefois montré ses limites, avec notamment les États-Unis qui n’ont pas ratifié ce protocole et le Canada qui en est sorti. En application de ce protocole, deux mécanismes de certification de projets de compensation carbone ont été développés : le mécanisme de mise en œuvre conjointe (Moc) et le mécanisme de développement propre (MDP), au sein desquels les secteurs agricoles et forestiers ne seront pas intégrés avant le milieu des années 2000.

Il faut attendre la COP17 de Durban, en 2011 (voir figure ci-dessous), pour que l’agriculture soit appréhendée comme un problème global, en étant à la fois cadré comme un enjeu d’atténuation et une question d’adaptation au changement climatique.

En effet, à la suite de la mobilisation d’acteurs hétérogènes en faveur de la notion de climate-smart agriculture et dans un contexte politique renouvelé, l’agriculture est intégrée à l’ordre du jour officiel de l’organe de la COP chargé des questions scientifiques et techniques (SBSTA, Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice). Cinq ateliers auront lieu entre 2013 et 2016.

La FAO a promu la climate-smart agriculture, ou l’agriculture climato-intelligente, dès la fin des années 2000. Cette notion vise à traiter trois objectifs principaux :

-

l’augmentation durable de la productivité et des revenus agricoles (sécurité alimentaire) ;

-

l’adaptation et le renforcement de la résilience face aux impacts des changements climatiques (adaptation) ;

-

et la réduction et/ou la suppression des émissions de gaz à effet de serre (l’atténuation), le cas échéant.)

À lire aussi :

Les sept familles de l’agriculture durable

Quelle place pour l’agriculture dans l’accord de Paris ?

Pourtant, s’il y a bien une journée consacrée à l’agriculture pendant la COP21 en 2015 en parallèle des négociations, l’accord de Paris aborde uniquement l’agriculture sous l’angle de la sécurité alimentaire et de la vulnérabilité des systèmes de production alimentaire.

Les écosystèmes agricoles et forestiers sont uniquement couverts par l’article 5 de l’accord de Paris, qui souligne l’importance de préserver et de renforcer les puits de carbone naturels et qui met en lumière des outils comme les paiements basés sur des résultats REDD+ et le mécanisme conjoint pour l’atténuation et l’adaptation des forêts (Joint Mitigation and Adaptation Mechanism for the Integral and Sustainable Management of Forests, ou JMA).

Une étape importante est franchie en 2017, avec la création de l’action commune de Koronivia (KJWA). Les ateliers se font maintenant en coopération avec les organes constitués au titre de la convention, par exemple le Fonds vert pour le climat. Les observateurs, dont les ONG et la recherche, participent également aux ateliers.

De 2018 à 2021, sept ateliers sont organisés (sur les méthodes d’évaluation de l’adaptation, les ressources en eau, le carbone du sol, etc.) et permettent à tous les États et parties prenantes (stakeholders) de partager leurs points de vue sur différents enjeux agricoles.

L’accélération de l’agenda climatique va dans le même temps permettre, pendant la COP26 de Glasgow, de prendre en charge la question des émissions de méthane, dont près de 40 % sont d’origine agricole, selon l’IEA (International Energy Agency).

Ryan Lim/Commission européenne, CC BY

Un « engagement mondial » (Global Methane Pledge) a été lancé en 2021 par l’Union européenne (UE) et les États-Unis, avec pour objectif de réduire les émissions mondiales de méthane de 30 % d’ici à 2030 par rapport à 2020. Il regroupe aujourd’hui 158 pays, sans toutefois que la Chine, l’Inde et la Russie figurent parmi les signataires.

Les points de blocage identifiés à l’issue des COP26 et COP27

En 2022, l’action commune de Koronivia arrivait à son terme. L’analyse des soumissions faites par les pays et les observateurs, dont la recherche, met en évidence la pluralité des façons de penser le lien entre les questions agricoles et les questions climatiques, ce qui va se traduire notamment par de fortes tensions entre des pays du Nord et des pays du Sud dans les négociations lors de la COP27 de Charm el-Cheikh en Égypte (2022).

Trois principaux points de blocage ont pu être identifiés entre différents pays des

Nords et des Suds. D’autres clivages sont également apparus, permettant ainsi de relativiser l’existence d’un Nord global et d’un Sud global qui s’opposeraient nécessairement.

Le premier a trait à l’utilisation du terme atténuation dans le texte de la décision de la COP. En effet, si toutes les parties étaient d’accord pour que figure dans le texte l’importance de l’adaptation de l’agriculture au changement climatique, l’Inde, soutenue par d’autres pays émergents restés plus en retrait, s’est montrée particulièrement réticente à voir apparaître aussi le terme atténuation.

Pour ce grand pays agricole, les enjeux d’atténuation ne doivent pas entraver la sécurité alimentaire des pays en développement et émergents. À quelques heures de la clôture des négociations, l’Inde a accepté que le terme atténuation figure dans la décision de la COP3/CP27, créant « l’initiative quadriennale commune de Charm el-Cheikh sur la mise en œuvre d’une action climatique pour l’agriculture et la sécurité alimentaire ».

Cet épisode montre à quel point il n’est pas acquis de penser en synergie les enjeux d’adaptation et d’atténuation pour de nombreux pays émergents et du Sud.

Un second point de blocage concernait la création d’une structure permanente affectée aux enjeux agricoles dans la CCNUCC. Cette demande, qui reste un point d’achoppement dans les négociations, est principalement portée par les pays du G77, même si des divergences notables existent entre les propositions faites.

Enfin, on peut identifier un enjeu lié à la place des systèmes alimentaires dans l’action climatique. Pour nombre de pays européens et émergents, la réflexion doit être faite à l’échelle des systèmes alimentaires : nos pratiques alimentaires dépendent étroitement des modes de production des produits agricoles, et une approche prenant en compte l’amont avec la production des intrants et l’éventuelle déforestation, et l’aval, avec le transport, le refroidissement, la transformation, et donc également les pertes et les gaspillages et les régimes alimentaires, est plus à même de permettre l’émergence de solutions gagnantes à tous niveaux.

Toutefois, d’un côté, le groupe Afrique préférait se focaliser sur le secteur agricole, une question déjà complexe à instruire. De l’autre côté, certains pays du Nord et aux économies en transition refusaient de voir apparaître le terme système alimentaire, l’hypothèse la plus probable étant la crainte de remettre en question la surconsommation de viande, la déforestation, ou encore le commerce, ce qu’ils souhaitent impérativement éviter.

Le terme système alimentaire a donc été rejeté dans le texte de l’initiative quadriennale commune de Charm el-Cheikh.

À lire aussi :

Climat : nos systèmes alimentaires peuvent devenir plus efficaces, plus résilients et plus justes

Les timides avancées de Charm el-Cheikh

Malgré ces points de tensions, l’initiative quadriennale commune de Charm el-Cheikh sur la mise en œuvre d’une action climatique pour l’agriculture et la sécurité alimentaire a été adoptée et cette décision de COP3/CP27 marque donc une étape décisive dans les négociations.

On notera tout de même que ce texte ne promeut ni l’agroécologie, qui aurait ouvert la voie à une refonte holistique des systèmes agricoles, ni l’agriculture climato-intelligente (climate-smart agriculture), davantage tournée vers les solutions technologiques. Aucun objectif chiffré de réduction des émissions de GES agricoles n’est discuté dans les COP ; aucune pratique n’a été encouragée ou stigmatisée (utilisation massive d’intrants chimiques, etc.).

La présidence émirienne de la COP28 a ensuite mis en haut de l’agenda politique cette question, en proposant la Déclaration sur l’agriculture durable, les systèmes alimentaires résilients et l’action climatique, signée par 160 pays.

Elle appelle les pays qui la rejoignent à renforcer la place des systèmes agricoles et alimentaires dans les contributions déterminées au niveau national et dans les plans nationaux d’adaptation et relatifs à la biodiversité.

Éditions Quae, 2025

Dans la foulée de la COP28, la FAO a proposé une feuille de route qui établit 120 mesures (dont des mesures dites agroécologiques) et étapes clés dans dix domaines pour l’adaptation et l’atténuation pour les systèmes agricoles et alimentaires. Elle vise à réduire de 25 % les émissions d’origine agricole et alimentaire, pour atteindre la neutralité carbone à l’horizon 2035, et à transformer d’ici 2050 ces systèmes en puits de carbone capturant 1,5 Gt de GES par an.

En définitive, l’initiative de Charm el-Cheikh portait sur l’agriculture et non pas sur les systèmes alimentaires, mais a donné lieu à un atelier, en juin 2025, sur les approches systémiques et holistiques en agriculture et dans les systèmes alimentaires, et le forum du Standing Committee on Finance de 2025 portera sur l’agriculture et les systèmes alimentaires durables. Le sujet fait donc son chemin dans les enceintes de la CCNUCC.

Ce chapitre a été écrit par Marie Hrabanski, Valérie Dermaux, Alexandre K. Magnan, Adèle Tanguy, Anaïs Valance et Roxane Moraglia.

![]()

Marie Hrabanski est membre du champ thématique stratégique du CIRAD sur le changement climatique et a reçu des financements de l’ANR APIICC (Evaluation des Plans et Instruments d’Innovation Institutionnelle pour lutter contre le changement climatique).

– ref. De 1992 à 2022, la laborieuse intégration de l’agriculture aux négociations climatiques – https://theconversation.com/de-1992-a-2022-la-laborieuse-integration-de-lagriculture-aux-negociations-climatiques-265335