Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Fellow for the Middle East at the Baker Institute, Rice University

Years of simmering tensions between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates exploded into the open on Dec. 30, 2025.

That’s when Saudi officials accused the UAE of backing separatist groups in Yemen and carried out an airstrike in the southern Yemeni city of Mukalla targeting an alleged shipment of weapons from the UAE to the Southern Transitional Council, one such separatist group.

Amid a rapidly rising war of words, Saudi-backed forces in Yemen recaptured two provinces that the STC had previously taken. Continued Saudi pressure resulted in the expulsion of the STC leader, Aidarous al-Zubaidi, from the Presidential Leadership Council – an eight-strong executive body that represents Yemen’s internationally recognized government. On Jan. 7, 2026, al-Zubaidi fled Yemen. That, plus the reported disbanding of the STC, brings a dramatic end to years of UAE influence in the south and dramatically fractures the coalition against the Houthis, a rebel group that currently controls most of northern and central Yemen.

For observers of Yemen it should come as little surprise that the country is now splitting apart along the two-country axis that has defined so much of the geopolitics of the Middle East since the 2011 Arab uprisings. It continues a long-term trend away from initial alignment between Saudi Arabia and the UAE over Yemen that risks not only reigniting conflict there but exposing a deeper power struggle that could fracture the entire region.

An uneasy alignment

The Saudis and Emiratis entered the Yemen conflict in alignment, forming an Arab coalition in March 2015 to push back the advance of Houthi rebels and forces loyal to the government of ousted president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Almost from the start, though, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi pursued different aims and objectives on the ground.

The Saudis viewed the conflict as a direct cross-border threat from the Houthis – a rebel force backed, in their view, by Iran. For the Emiratis, meanwhile, the priority was acting assertively against Islamist groups in southern Yemen.

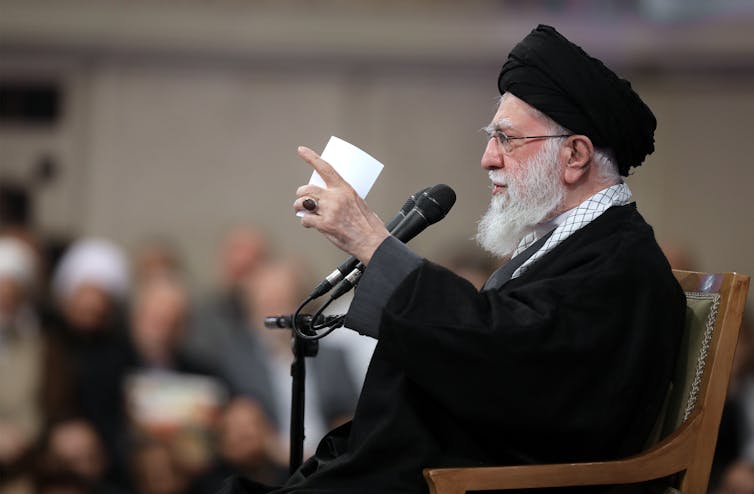

Hamad Al Kaabi/Emirati Ministry of Presidential Affairs via AP

Initially, decision-making at the highest level of the intervening coalition in Yemen reflected a close alignment between Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh and then-Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed in Abu Dhabi.

The two were seen as acting in lockstep in the mid-2010s across the region, including the blockade of Qatar in 2017 over the smaller Gulf state’s alleged links to terrorist groups.

From 2015 to 2018, UAE’s Mohammed bin Zayed played a key role in facilitating Mohammed bin Salman’s rapid rise to authority in Saudi Arabia.

A mentor-mentee relationship was seen by many analysts of Gulf affairs to have developed between the two as Mohammed bin Zayed, 24 years the senior, became almost a father figure to the hitherto little-known Mohammed bin Salman while singing his praises in Western capitals, including Washington, D.C.

The coalition frays

But the cozy relationship between Saudi Arabia and the UAE didn’t last.

A range of factors contributed to the cooling between the two states. These included the abrupt Emirati decision in July 2019 to withdraw its troops from the front line in the anti-Houthi struggle and refocus UAE support for local groups in southern Yemen, including the STC, which had been established in 2017 with visible Emirati backing.

Saudi officials expressed surprise at the UAE decision. From the Saudi perspective, UAE objectives in Yemen had been fulfilled after the recapture of critical southern cities, including Aden and Mukalla in 2015 and 2016.

In their reading, it was the Saudis, not the Emiratis, who were bogged down in an unwinnable campaign against the Houthis. The subsequent fraying of a power-sharing agreement between the STC and Saudi-backed government forces caused additional friction between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi.

Elsewhere, signs emerged that the Emirati leadership did not share the Saudi openness to healing the rift with Qatar – even as U.S. officials signaled frustration at a stalemate that damaged U.S. partnerships in the region and gave succor to adversaries such as Iran.

Clashing visions

As the potency of the turbulent post-Arab Spring decade ebbed, the glue that had brought Riyadh and Abu Dhabi closer together in their desire to reassert control over the post-2011 regional order weakened.

On two occasions, in November 2020 and July 2021, Emirati and Saudi officials sparred at OPEC+ meetings over preferred oil price and output levels, and in the summer of 2021 the Saudis tightened rules on what passed for tariff-free status in a move that appeared to target goods that passed through the many economic free zones in the UAE.

Also that year, Saudi officials decreed that companies wishing to do business with government agencies in the kingdom would have to locate their regional headquarters in the kingdom by 2024 – a move seemingly aimed at Dubai’s long-standing leadership in regional business circles. The launch of a new Saudi airline, Riyadh Air, and the emphasis placed in Riyadh on developing travel, tourism, entertainment and hospitality as part of its Vision 2030 plan also took aim at sectors in which the UAE has long enjoyed first-mover advantage.

However, the real significance of the Yemen bust-up is that it demonstrates the degree of divergence in Saudi and Emirati visions of regional order. The Saudi preference is for “de-risking” – that is, making the region appear safe and stable for would-be outside investors.

This fits the Saudi’s resolute focus on economic development and delivering Vision 2030.

But it clashes directly with the perceived Emirati tolerance for risk-taking in regional affairs. Abu Dhabi is widely believed to have backed armed nonstate groups in Libya and supports Sudan’s rebel Rapid Support Forces, in addition to its known links with the STC in Yemen.

Libya and Sudan were less central to Saudi security concerns, but the STC’s capture of the southeastern Yemeni provinces of Hadramout and Mahra in early December crossed Saudi red lines.

The fact that the STC advance began on Dec. 3, the day Gulf Cooperation Council leaders met for their annual summit, was also seen by Saudi policymakers as a major provocation. They assumed that the offensive must have received a green light from Abu Dhabi.

An off-ramp to tensions?

While ties are unlikely to rupture between Saudis and Emiratis in the same way they both did with Qatar in 2017, the current trajectory between these two key U.S. allies in the Middle East is not good.

There is no desire within the Gulf Cooperation Council for another such rift, and the Emirati decision to withdraw its remaining forces from Yemen and leave the STC to its own fate suggests there are still off-ramps to defuse tensions.

Yet the headstrong leaders in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are all but certain to continue on a divergent pathway, I believe. And this could manifest in multiple ways, including growing economic competition in areas such as AI investments, where the Saudis, once again, are playing catch-up to the UAE. These are areas of competition that could only intensify as both Gulf states try to gain an advantage with a transactional Trump administration.

Given the challenges that the wide region faces – not only in Yemen but also in war-torn Gaza and Lebanon, a Syria emerging from civil conflict, and now, potentially, an Iran embroiled in protest – a fractured vision of regional order between the Gulf’s two biggest players does not bode well for the future.

![]()

Kristian Coates Ulrichsen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Saudi-UAE bust-up over Yemen was only a matter of time − and reflects wider rift over vision for the region – https://theconversation.com/saudi-uae-bust-up-over-yemen-was-only-a-matter-of-time-and-reflects-wider-rift-over-vision-for-the-region-273083