Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Mark W. Post, Senior Lecturer in Linguistics, University of Sydney

If you are fluent in any language other than English, you have probably noticed that some things are impossible to translate exactly.

A Japanese designer marvelling at an object’s shibui (a sort of simple yet timelessly elegant beauty) may feel stymied by English’s lack of a precisely equivalent term.

Danish hygge refers to such a unique flavour of coziness that entire books seem to have been needed to explain it.

Portuguese speakers may struggle to convey their saudade, a mixture of yearning, wistfulness and melancholy. Speakers of Welsh will have an even harder time translating their hiraeth, which can carry a further sense of longing after one’s specifically Celtic culture and traditions.

Imprisoned by language

The words of different languages can divide and package their speakers’ thoughts and experiences differently, and provide support for the theory of “linguistic relativity”.

Also known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, this theory derives in part from the American linguist Edward Sapir’s 1929 claim that languages function to “index” their speakers’ “network of cultural patterns”: if Danish speakers experience hygge, then they should have a word to talk about it; if English speakers don’t, then we won’t.

Mitchell Orr/Unsplash

Yet Sapir also went a step further, claiming language users “do not live in the objective world alone […] but are very much at the mercy” of their languages.

This stronger theory of “linguistic determinism” implies English speakers may be imprisoned by our language. In this, we actually cannot experience hygge – or at least, not in the same way that a Danish person might. The missing word implies a missing concept: an empty gap in our world of experience.

Competing theories

Few theories have proven as controversial. Sapir’s student Benjamin Lee Whorf famously claimed in 1940 that the Hopi language’s lack of verb tenses (past, present, future) indicated its speakers have a different “psychic experience” of time and the universe than Western physicists.

This was countered by a later study devoting nearly 400 pages to the language of time in Hopi, which included concepts such as “today”, “January” and – yes – discussions of actions happening in the present, past and future.

Even heard of “50 Inuit words for snow?” Whorf again.

Although the number he actually claimed was closer to seven, this was later said to be both too many and too few. (It depends on how you define a “word”.)

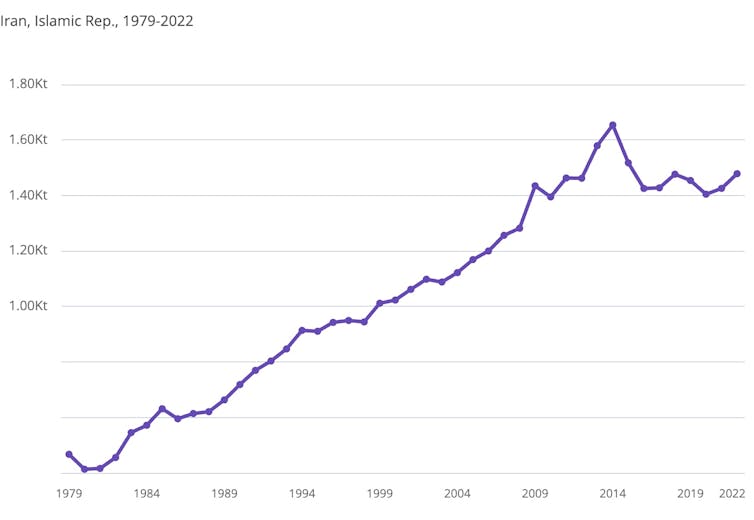

UC Berkeley, Department of Geography

More recently, the anthropological linguist Dan Everett claimed the Amazonian Pirahã language lacks “recursion”, or the capacity to put one sentence inside another (“{I trust {you’ll come {to realise that {my theory is better.}}}}”).

If true, this would suggest that Pirahã differs in the exact property that Noam Chomsky has argued to be the principal defining property of any human language.

Once again, Everett’s claims have been argued both to go too far and not far enough. The cycle would appear to be endless, such that two excellent recent books on the topic have adopted almost diametrically opposite perspectives – even down to the opposite wording of their titles!

Language as a comfortable house

There is truth in both perspectives.

At least some aspects of human languages must be identical or nearly so, since they are all used by members of the same human species, with the same sorts of bodies, brains and patterns of communication.

Yet recent increases in understanding of the world’s Indigenous languages have taught us two important additional lessons. First, there is far more diversity among the world’s languages than previously believed. Second, differences are often related to the patterns of culture and environment in which languages are traditionally spoken.

Mark Post

For example, in many Himalayan languages, an expression like “that house” comes in three flavours: “that-house-upward”, “that-house-downward” and “that-house-on-the-same-level” – a reflection of the mountainous area these speakers live in.

When their speakers migrate to lower-elevation regions, the system may shift from “upward/downward” to “upriver/downriver”. If there is no large enough river present then the distinction may disappear.

In Indigenous Aslian languages of peninsular Malaysia, there are large vocabularies referring to finely-distinguished natural odours. This is an index of the richly diverse foraging environment of their speakers.

Studies of small, tightly-knit communities like the Milang of northeastern India have revealed how languages can require speakers to mark their information source: whether a statement is the general knowledge of one’s social group, or is arrived at through a different type of source – such as hearsay, or deduction from evidence.

Speakers of languages with such “evidentiality” systems can learn to speak languages – like English – without them. Yet native language habits turn out to be hard to break. One recent study showed speakers of some languages with evidentiality add words like “reportedly” or “seemingly” into their statements more often than native English speakers.

Human languages may not be a prison their speakers cannot escape from. They may be more like comfortable houses one finds it difficult to leave. Although a word from another language can always be borrowed, its unique cultural meanings may always remain just a little bit out of reach.

![]()

Mark W. Post does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Impossible translations: why we struggle to translate words when we don’t experience the concept – https://theconversation.com/impossible-translations-why-we-struggle-to-translate-words-when-we-dont-experience-the-concept-267521