Source: The Conversation – UK – By Dafydd Townley, Teaching Fellow in US politics and international security, University of Portsmouth

One year into his second term of office, Donald Trump’s foreign policy aspirations have led him to variously lay claim to Canada, the Panama Canal and, most contentiously at present, Greenland. He has kidnapped the head of state of Venezuela, saying that the US can run the country and exploit its oil, and he has issued threats against the sovereignty of Colombia, Mexico and Cuba.

Whatever the 47th president’s motivations, his expansionist vision has echoes of a little-known organisation that flourished briefly in the middle decades of the 19th century: the Knights of the Golden Circle. The Knights were a secret society founded in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1854 by Virginian doctor George W.L. Bickley.

Membership of the group is largely hidden from historians due to the secretive nature of the organisation. But legend suggests that its leaders included the likes of confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest (who would go on to be the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan) and Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

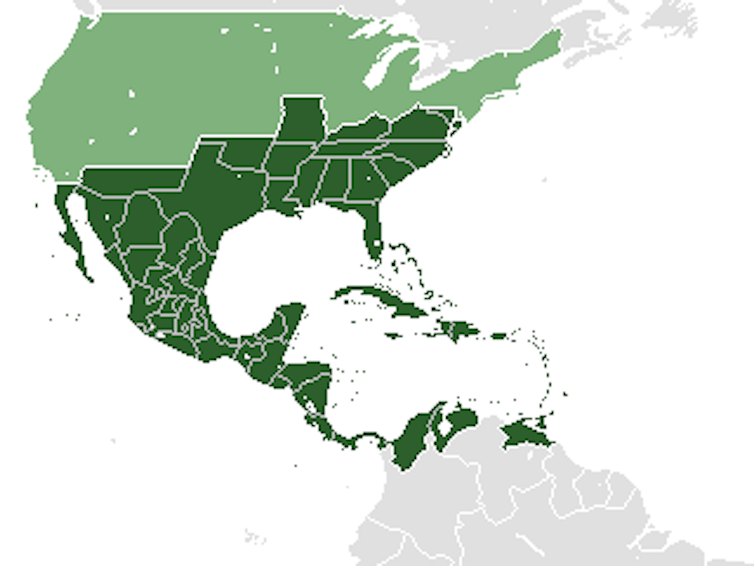

The society’s name was chosen to reflect the wealth that would be created by establishing a slaveholding empire that would initially consist of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. The so-called “Golden Circle”, with its headquarters in Havana, Cuba, would encompass much of the world’s supply of cash crops such as tobacco, rice, cotton, sugar and coffee, and the production of each depended on significant enslaved workforces.

The initial intention was not to have an independent empire but to annex the area to the American south, strengthening the cause of slavery. But the group shifted tactics as tensions escalated in the late 1850s, especially after the the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision (1857) that ruled that African Americans were not and could never be citizens. And as the abolitionist movement in the north gathered pace, the Golden Circle society adapted to support the secession of the southern states from the Union to be absorbed into the other Golden Circle territories.

The exact number of members of the Knights of the Golden Circle is unknown. Bickley claimed it had 115,000 members at one point – although this seems unlikely due to Bickley’s failure to raise troops to invade Mexico.

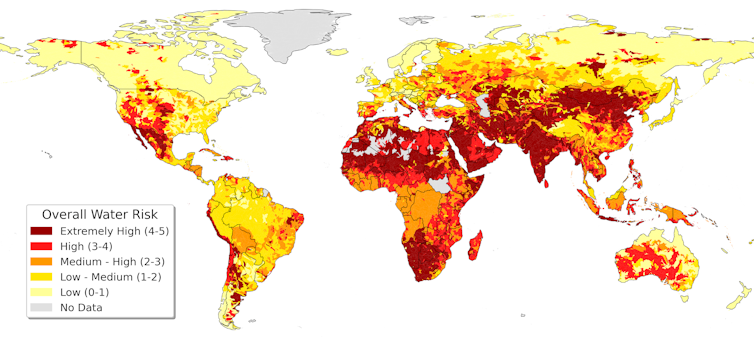

The Knights’ goals were not simply territorial expansion. They were ambitions of ideological conquests rooted in the continuation of slavery, as viewed through the lens of a “manifest destiny”: the idea that the white man should expand its dominance across the continent of America to the exclusion of native populations.

While the organisation’s influence was limited, it reflected the 19th-century American premise that territorial expansion could forever secure a social order built on hierarchy and chattel slavery.

Trump’s Maga vision

Fast forward to the present day, and American imperialist expansion no longer wears the uniform of secret societies such as the Knights. Instead, it emerges through presidential rhetoric, policy signalling and deliberate ambiguity.

On January 20 2025, Donald Trump was sworn in as the 47th president of the United States. His first year in office has seen profound changes both in his own country and across the globe. In this series, The Conversation’s international affairs team aims to capture the mood after the first year of Trump’s second coming.

Under Trump, America’s ambitions in the western hemisphere have been framed as annexations driven by hemispheric dominance. Trump unironically called it the “Donroe doctrine”, a personalised and transactional reinterpretation of the Monroe doctrine’s core claim: that the Americas are solely within the United States’ sphere of influence.

Where the 1823 Monroe doctrine warned European powers against further colonisation while professing American restraint, Trump’s version dispenses with the pretence of mutual sovereignty. It treats neighbouring states not as equals but as strategic assets or bargaining chips. The language is typically Trumpian (blunt and improvised) but it argues that external powers have no role in the governance of the western hemisphere, and that the United States has the final say-so.

Cuba is at the centre of this worldview. While Trump has not openly advocated annexing the island, he has attempted to use coercive pressure as a substitute for territorial control. Efforts to disrupt Cuban energy supplies and renewed talk of regime change echo traditional American treatment of Cuba as an unfinished project. Consequently, Trump’s Cuba policy resembles the establishment of an informal American empire.

Spesh531/Wikipedia, CC BY-ND

The Knights of the Golden Circle imagined Cuba not just within the American sphere of influence but as territory to be absorbed. Their obsession with Havana as the Golden Circle’s centre reflected an understanding that southern power depended on control of the Caribbean. Trump’s posture is less explicit, but the strategy is very similar. Cuba is viewed as a prize within America’s reach and yet denied.

The same logic appears elsewhere in the Americas. Trump’s threats toward Mexico blur the line between cooperation and coercion. America’s neighbours’ sovereignty becomes negotiable when framed as an American security problem. Pressure on Venezuela and Columbia also reflects a willingness to treat political outcomes in the Americas as matters of US entitlement.

What distinguishes the so-called Trump corollary from previous American hemispheric dominance is its tone. It is unapologetically hierarchical and dismisses multilateral norms. It harks back to a time when the US could act first and justify itself later. Where cold war policymakers cloaked intervention in ideological language, Trump’s rhetoric is strikingly transactional. Influence is something to be purchased or compelled.

This brings the comparison with the Knights of the Golden Circle into sharper focus. The Knights had a secret vision of empire, brought to life by slavery and racial hierarchy. Trump’s ambitions are in the public sphere, filtered through state power. But both reflect that geography confers entitlement and that the Americas exist in a fundamentally different moral category.

In this light, Trump’s policy is not a radical break with American history but an unvarnished return to its imperial ambitions. The map may no longer be redrawn by conquest, but the logic that once animated the Golden Circle, one of hemispheric control as destiny, has not disappeared. It has merely learnt to speak in the idiom of modern populism.

![]()

Dafydd Townley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. 19th-century plan for a slaving empire based in US deep south and Caribbean resonates with Trump’s foreign policy today – https://theconversation.com/19th-century-plan-for-a-slaving-empire-based-in-us-deep-south-and-caribbean-resonates-with-trumps-foreign-policy-today-272871