Source: The Conversation – UK – By Mark Williams, Professor of Palaeobiology, University of Leicester

The age of humans is increasingly an age of sameness. Across the planet, distinctive plants and animals are disappearing, replaced by species that are lucky enough to thrive alongside humans and travel with us easily. Some scientists have a word for this reshuffling of life: the Homogenocene.

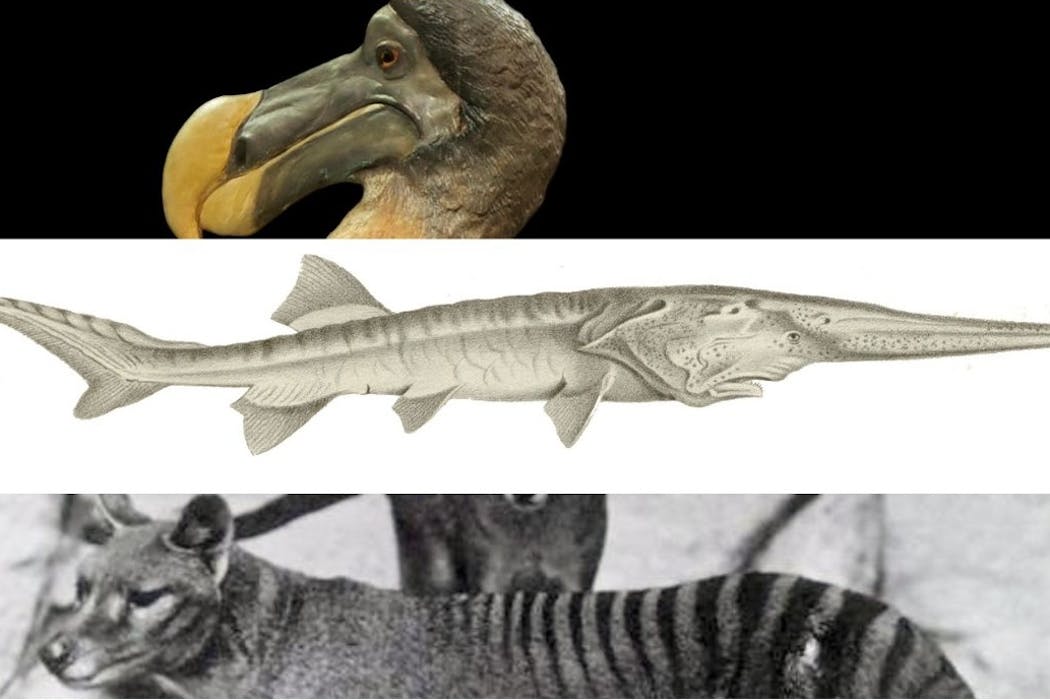

Evidence for it is found in the world’s museums. Storerooms are full of animals that no longer walk among us, pickled in spirit-filled jars: coiled snakes, bloated fish, frogs, birds. Each extinct species marks the removal of a particular evolutionary path from a particular place – and these absences are increasingly being filled by the same hardy, adaptable species, again and again.

One such absence is embodied by a small bird kept in a glass jar in London’s Natural History Museum: the Fijian Bar-winged rail, not seen in the wild since the 1970s. It seems to be sleeping, its eyes closed, its wings tucked in along its back, its beak resting against the glass.

A flightless bird, it was particularly vulnerable to predators introduced by humans, including mongooses brought to Fiji in the 1800s. Its disappearance was part of a broad pattern in which island species are vanishing and a narrower set of globally successful animals thrive in their place.

It’s a phenomenon that was called the Homogenocene even before a similar term growing in popularity, the Anthropocene, was coined in 2000. If the Anthropocene describes a planet transformed by humans, the Homogenocene is one ecological consequence: fewer places with their own distinctive life.

It goes well beyond charismatic birds and mammals. Freshwater fish, for instance, are becoming more “samey”, as the natural barriers that once kept populations separate – waterfalls, river catchments, temperature limits – are effectively blurred or erased by human activity. Think of common carp deliberately stocked in lakes for anglers, or catfish released from home aquariums that now thrive in rivers thousands of miles from their native habitat.

Meanwhile, many thousands of mollusc species have disappeared over the past 500 years, with snails living on islands also severely affected: many are simply eaten by non-native predatory snails. Some invasive snails have become highly successful and widely distributed, such as the giant African snail that is now found from the Hawaiian Islands to the Americas, or South American golden apple snails rampant through east and south-east Asia since their introduction in the 1980s.

Homogeneity is just one facet of the changes wrought on the Earth’s tapestry of life by humans, a process that started in the last ice age when hunting was likely key to the disappearance of the mammoth, giant sloth and other large mammals. It continued over around 11,700 years of the recent Holocene epoch – the period following the last ice age – as forests were felled and savannahs cleared for agriculture and the growth of farms and cities.

Over the past seven decades changes to life on Earth have intensified dramatically. This is the focus of a major new volume published by the Royal Society of London: The Biosphere in the Anthropocene.

The Anthropocene has reached the ocean

Life in the oceans was relatively little changed between the last ice age and recent history, even as humans increasingly affected life on land. No longer: a feature of the Anthropocene is the rapid extension of human impacts through the oceans.

This is partly due to simple over-exploitation, as human technology post-second world war enabled more efficient and deeper trawling, and fish stocks became seriously depleted.

Drew McArthur / shutterstock

Partly this is also due to the increasing effects of fossil-fuelled heat and oxygen depletion spreading through the oceans. Most visibly, this is now devastating coral reefs.

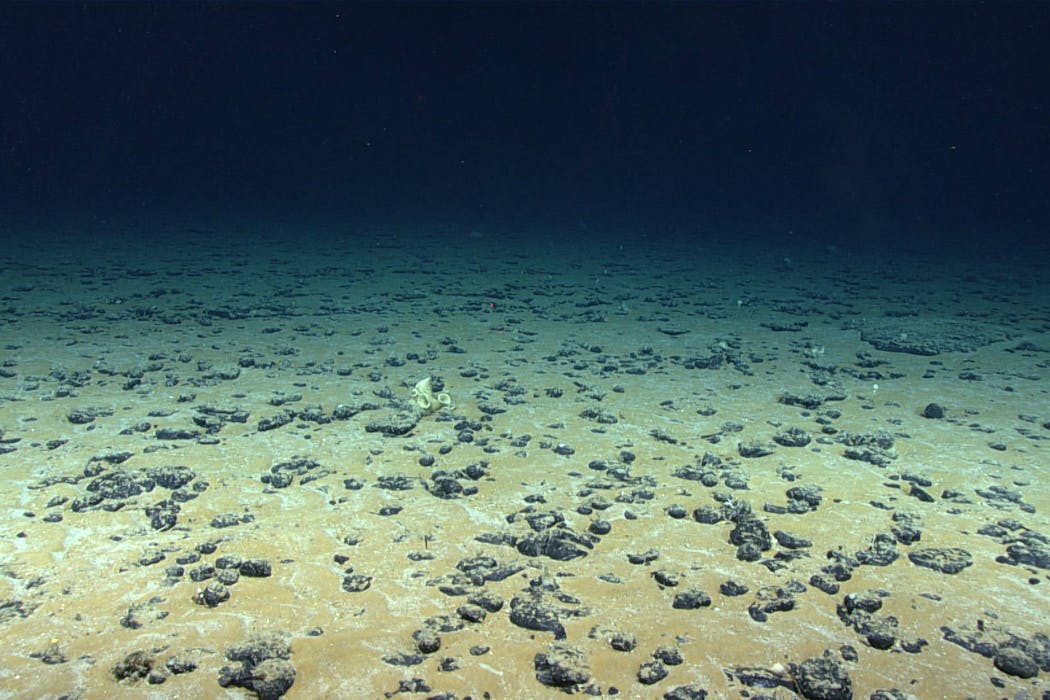

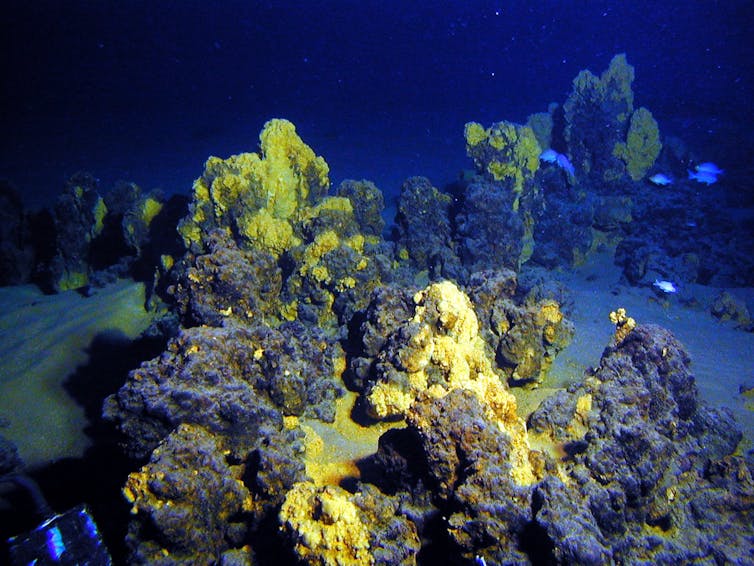

Out of sight, many animals are being displaced northwards and southwards out of the tropics to escape the heat; these conditions are also affecting spawning in fish, creating “bottlenecks” where life cycle development is limited by increasing heat or a lack of oxygen. The effects are reaching through into the deep oceans, where proposals for deep sea mining of minerals threaten to damage marine life that is barely known to science.

And as on land and in rivers, these changes are not just reducing life in the oceans – they’re redistributing species and blurring long-standing biological boundaries.

Local biodiversity, global sameness

Not all the changes to life made by humans are calamitous. In some places, incoming non-native species have blended seamlessly into existing environments to actually enhance local biodiversity.

In other contexts, both historical and contemporary, humans have been decisive in fostering wildlife, increasing the diversity of animals and plants in ecosystems by cutting or burning back the dominant vegetation and thereby allowing a greater range of animals and plants to flourish.

In our near-future world there are opportunities to support wildlife, for instance by changing patterns of agriculture to use less land to grow more food. With such freeing-up of space for nature, coupled with changes to farming and fishing that actively protect biodiversity, there is still a chance that we can avoid the worst predictions of a future biodiversity crash.

But this is by no means certain. Avoiding yet more rows of pickled corpses in museum jars will require a concerted effort to protect nature, one that must aim to help future generations of humans live in a biodiverse world.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Welcome to the ‘Homogenocene’: how humans are making the world’s wildlife dangerously samey – https://theconversation.com/welcome-to-the-homogenocene-how-humans-are-making-the-worlds-wildlife-dangerously-samey-274092