Source: The Conversation – (in Spanish) – By Arantxa Serrano Cañadas, Contratada investigadora predoctoral en área de Derecho Financiero y Tributario – Economía circular, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

El anteproyecto de Ley de Consumo Sostenible, aprobado el pasado mes de julio por el Consejo de Ministros, supone el intento más ambicioso de los últimos años para reorientar el modelo de consumo en España hacia mayores estándares de durabilidad, transparencia e impacto ambiental reducido.

Se trata de una norma transversal que transpone las directivas de la Unión Europea (UE) 2024/825 y 2024/1799, centradas respectivamente en combatir las prácticas verdes engañosas y en promover el derecho a reparar. Su aprobación podría modificar de forma sustancial el modo en que los consumidores eligen productos, cómo los diseñan las empresas y cuáles son los incentivos económicos asociados a reparar en lugar de sustituir.

La norma, que entrará en vigor entre julio y septiembre de 2026, interviene sobre dos pilares del ordenamiento: la Ley de Competencia Desleal y el texto refundido de la Ley General para la Defensa de los Consumidores y Usuarios. Aunque este método de “injerto normativo” ha sido criticado por generar dispersión y falta de sistematicidad, constituye la vía que ha escogido el legislador para dar cumplimiento a las obligaciones europeas.

Más información, menos greenwashing

Una de las áreas con mayor impacto es la regulación de las alegaciones medioambientales. El anteproyecto incorpora la categoría de “ecoimpostura”, entendida como el uso de declaraciones ambientales vagas, no verificables o directamente engañosas. Esta figura deriva de la Directiva (UE) 2024/825, que busca evitar que el término “sostenible” se utilice como reclamo sin respaldo técnico.

En consecuencia, la publicidad que atribuya a un bien características verdes deberá basarse en certificaciones verificables, trazabilidad y criterios objetivos. La norma también prohíbe los distintivos ambientales poco transparentes y somete a especial escrutinio las menciones globales como “cero emisiones”, que pueden ocultar compensaciones externas o metodologías de cálculo discutibles.

Además, la ley resucita una prohibición clásica: la “publicidad del miedo”. Será ilícito promover servicios, especialmente en seguridad, mediante mensajes que exploten ansiedad o riesgo sin aportar datos verificables. Se trata de una respuesta a prácticas que combinan emocionalidad y opacidad, y que condicionan decisiones de compra alejadas de la racionalidad económica.

Leer más:

Los límites del miedo en la narrativa del cambio climático

Derecho a reparar: de la retórica a la obligación jurídica

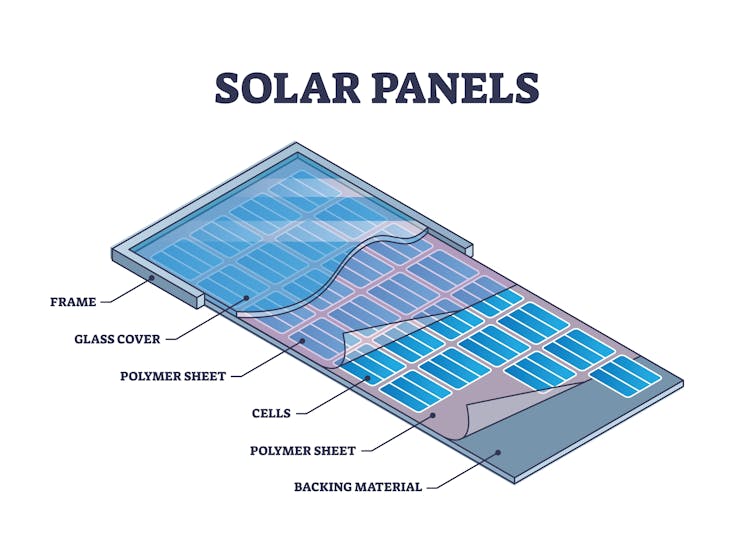

El núcleo del texto se encuentra en el derecho a reparar. La Directiva (UE) 2024/1799 obliga a redefinir las relaciones entre consumidores, vendedores y fabricantes. Los fabricantes deberán reparar determinados bienes (por ejemplo: grandes electrodomésticos de uso doméstico y teléfonos móviles) más allá del período de garantía legal cuando estos productos cuenten con normas europeas que establezcan sus requisitos de reparabilidad.

Esta obligación se ve reforzada por tres instrumentos:

-

Formulario europeo de información sobre la reparación: documento estandarizado que detalla precio, plazos y condiciones, y que permitirá comparar ofertas en un mercado que hasta ahora sufría una asimetría informativa estructural. Su uso garantiza el cumplimiento de los deberes de información precontractual por parte del reparador.

-

Plataforma europea en línea de reparaciones: España contará con una sección nacional que incluirá reparadores, vendedores de bienes reacondicionados y entidades que participen en iniciativas comunitarias de reparación. Esta plataforma introduce competencia en un mercado históricamente atomizado, facilitando el acceso a reparadores y reduciendo costes de búsqueda.

-

Sistema de financiación parcial de reparaciones: mecanismo novedoso en el derecho español por el que fabricantes, importadores o distribuidores cofinancian reparaciones una vez agotada la garantía legal. Su diseño es decreciente en el tiempo y solo se activará cuando no exista garantía comercial o esta sea más corta que el periodo previsto por la ley.

Este sistema pretende corregir el sesgo económico que empuja al reemplazo: cuando reparar es tan caro como comprar un bien nuevo, la decisión racional del consumidor se orienta hacia el reemplazo. El mecanismo busca invertir esa lógica.

Transparencia en precios y durabilidad

El anteproyecto aborda también la reduflación –la reducción de cantidades manteniendo precio– mediante nuevas exigencias informativas. Aunque la reduflación no es ilícita per se, sí puede resultar engañosa si el consumidor no percibe la reducción efectiva del contenido. La norma obliga a informar de forma clara y visible cuando se produzca este cambio, reforzando la comparabilidad de precios unitarios.

Asimismo, se introduce la “garantía comercial de durabilidad”, que permitirá señalar, mediante una etiqueta armonizada, si el producto cuenta con un compromiso de durabilidad superior al mínimo legal y sin coste adicional. Esta etiqueta aspira a crear un incentivo reputacional para los fabricantes de productos robustos y reparables, y a generar una señal fiable para el consumidor en un mercado saturado de información.

Leer más:

Nuevas normas de etiquetado de la UE para que las baterías duren más y no lleguen a los vertederos

Implicaciones económicas y sociales

Las obligaciones derivadas del anteproyecto pueden generar costes de adaptación relevantes para empresas, particularmente pymes del sector tecnológico y electrodoméstico. La disponibilidad de piezas de repuesto, la documentación técnica y la obligación posgarantía exigen reorganizar cadenas de suministro y, en algunos casos, rediseñar productos. Sin embargo, estos efectos deben analizarse a la luz de beneficios sistémicos: reducción de residuos, impulso a la economía circular y creación de negocios locales de reparación.

Para los consumidores, la norma incrementa la tutela jurídica y reduce incertidumbre: alargar la vida útil de bienes, ofrecer información fiable y evitar prácticas comerciales engañosas refuerza el comportamiento racional y disminuye costes a largo plazo.

Aplicable solo a algunos productos

Del análisis conjunto del anteproyecto y la doctrina se desprende un aspecto poco discutido: el riesgo de generar una asimetría regulatoria de reparabilidad. El derecho a reparar se aplicará solo a determinados productos designados por la Unión Europea. Esto puede incentivar a algunos fabricantes a desplazar su catálogo hacia productos no incluidos en la lista de reparabilidad para evitar obligaciones de reparación posgarantía.

Este efecto, aunque indirecto, es relevante y exige que el legislador monitorice la evolución del mercado para evitar distorsiones competitivas y garantizar que la transición ecológica no quede limitada por el perímetro de la regulación europea. La propia doctrina advierte de la necesidad de una ley autónoma de consumo sostenible que permita integrar coherentemente estas obligaciones y evitar vacíos sistémicos.

![]()

Arantxa Serrano Cañadas recibe fondos de un contrato predoctoral de investigación cofinanciado por el Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, así como por la Unión Europea.

Gemma Patón García recibe fondos para proyectos de investigación del Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MICIU). Miembro del Consejo Asesor de Economía Circular del Ministerio de Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico (MITERD). Miembro de la Asociación para el Progreso y Sostenibilidad de las Sociedades (ASYPS).

– ref. El nuevo anteproyecto de Ley de Consumo Sostenible obliga a reparar ciertos productos más allá del período de garantía – https://theconversation.com/el-nuevo-anteproyecto-de-ley-de-consumo-sostenible-obliga-a-reparar-ciertos-productos-mas-alla-del-periodo-de-garantia-269738