Source: The Conversation – France in French (3) – By Aaron Coy Moulton, Associate Professor of Latin American History, Stephen F. Austin State University

Dans les années 1950 déjà, les États-Unis intervenaient contre un gouvernement démocratiquement élu au nom d’une menace idéologique, tout en protégeant des intérêts économiques majeurs. Mais si les ressorts se ressemblent, les méthodes et le degré de transparence ont profondément changé.

Dans la foulée de la frappe militaire américaine qui a conduit à l’arrestation du président vénézuélien Nicolás Maduro le 3 janvier 2026, l’administration Trump a surtout affiché son ambition d’obtenir un accès sans entrave au pétrole du Venezuela, reléguant au second plan des objectifs plus classiques de politique étrangère comme la lutte contre le trafic de drogue ou le soutien à la démocratie et à la stabilité régionale.

Lors de sa première conférence de presse après l’opération, le président Donald Trump a ainsi affirmé que les compagnies pétrolières avaint un rôle important à jouer et que les revenus du pétrole contribueraient à financer toute nouvelle intervention au Venezuela.

Peu après, les animateurs de « Fox & Friends » ont interpelé Trump sur ces prévisions :

« Nous avons les plus grandes compagnies pétrolières du monde », a répondu Trump, « les plus importantes, les meilleures, et nous allons y être très fortement impliqués ».

En tant qu’historien des relations entre les États-Unis et l’Amérique latine, je ne suis pas surpris de voir le pétrole, ou toute autre ressource, jouer un rôle dans la politique américaine à l’égard de la région. Ce qui m’a en revanche frappé, c’est la franchise avec laquelle l’administration Trump reconnaît le rôle déterminant du pétrole dans sa politique envers le Venezuela.

Comme je l’ai détaillé dans mon livre paru en 2026, Caribbean Blood Pacts: Guatemala and the Cold War Struggle for Freedom (NDT : livre non traduit en français), les interventions militaires américaines en Amérique latine ont, pour l’essentiel, été menées de manière clandestine. Et lorsque les États-Unis ont orchestré le coup d’État qui a renversé le président démocratiquement élu du Guatemala en 1954, ils ont dissimulé le rôle qu’avaient joué les considérations économiques dans cette opération.

Un « poulpe » puissant

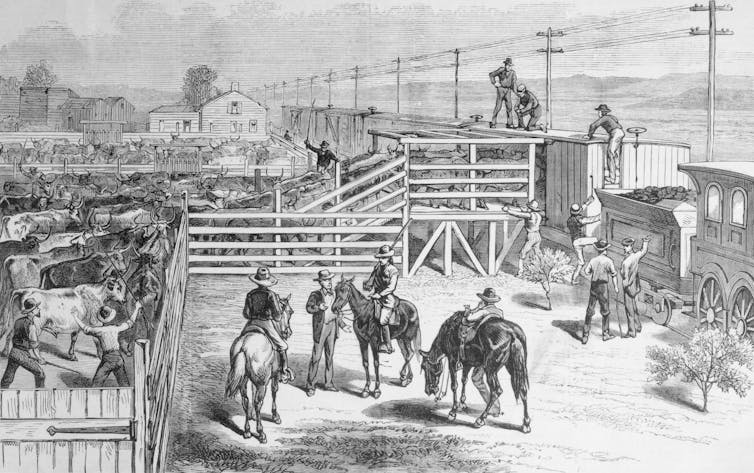

Au début des années 1950, le Guatemala était devenu l’une des principaux fournisseurs de bananes pour les Américains, comme c’est d’ailleurs toujours le cas aujourd’hui.

La United Fruit Company possédait alors plus de 220 000 hectares de terres guatémaltèques, en grande partie grâce aux accords conclus avec les dictatures précédentes. Ces propriétés reposaient sur le travail intensif d’ouvriers agricoles pauvres, souvent chassés de leurs terres traditionnelles. Leur rémunération était rarement stable, et ils subissaient régulièrement des licenciements et des baisses de salaire.

Basée à Boston, cette multinationale a tissé des liens avec des dictateurs et des responsables locaux en Amérique centrale, dans de nombreuses îles des Caraïbes et dans certaines régions d’Amérique du Sud afin d’acquérir d’immenses domaines destinés aux chemins de fer et aux plantations de bananes.

Les populations locales la surnommaient le « pulpo » – « poulpe » en espagnol – car l’entreprise semblait intervenir dans la structuration de la vie politique, de l’économie et de la vie quotidienne de la région. En Colombie, le gouvernement a par exemple brutalement réprimé une grève des travailleurs de la United Fruit en 1928, faisant des centaines de morts. Cet épisode sanglant de l’histoire colombienne a d’ailleurs servi de base factuelle à une intrigue secondaire de « Cent ans de solitude », le roman épique de Gabriel García Márquez, lauréat du prix Nobel de littérature en 1982.

L’influence apparemment sans limites de l’entreprise dans les pays où elle opérait a nourri le stéréotype des nations d’Amérique centrale comme des « républiques bananières ».

La révolution démocratique guatémaltèque

Au Guatemala, pays historiquement marqué par des inégalités extrêmes, une vaste coalition s’est formée en 1944 pour renverser la dictature répressive lors d’un soulèvement populaire. Inspirée par les idéaux antifascistes de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, cette coalition ambitionnait de démocratiser le pays et de rendre son économie plus équitable.

Après des décennies de répression, les nouveaux dirigeants ont offert à de nombreux Guatémaltèques leur premier contact avec la démocratie. Sous la présidence de Juan José Arévalo, élu démocratiquement et en fonction de 1945 à 1951, le gouvernement a mis en place de nouvelles protections sociales ainsi qu’un code du travail légalisant la création et l’adhésion à des syndicats, et instaurant la journée de travail de huit heures.

En 1951, lui a succédé Jacobo Árbenz, lui aussi président démocratiquement élu.

Sous Árbenz, le Guatemala a mis en œuvre en 1952 un vaste programme de réforme agraire, attribuant des parcelles non exploitées aux ouvriers agricoles sans terre. Le gouvernement guatémaltèque affirmait que ces politiques permettraient de bâtir une société plus équitable pour la majorité indigène et pauvre du pays.

United Fruit a dénoncé ces réformes comme le produit d’une conspiration mondiale. L’entreprise affirmait que la majorité des syndicats du pays étaient contrôlés par des communistes mexicains et soviétiques, et présentait la réforme agraire comme une manœuvre visant à détruire le capitalisme.

Pression sur le Congrès pour une intervention

Au Guatemala, United Fruit a cherché à rallier le gouvernement américain à son combat contre les politiques menées par Árbenz. Si ses dirigeants se plaignaient bien du fait que les réformes guatémaltèques nuisaient à ses investissements financiers et alourdissaient ses coûts de main-d’œuvre, ils présentaient aussi toute entrave à leurs activités comme faisant partie d’un vaste complot communiste.

L’entreprise a mené l’offensive à travers une campagne publicitaire aux États-Unis et en exploitant la paranoïa anticommuniste dominante de l’époque.

Dès 1945, les dirigeants de la United Fruit Company ont commencé à rencontrer des responsables de l’administration Truman. Malgré le soutien d’ambassadeurs favorables à leur cause, le gouvernement américain ne semblait pas disposé à intervenir directement dans les affaires guatémaltèques. L’entreprise s’est alors tournée vers le Congrès, recrutant les lobbyistes Thomas Corcoran et Robert La Follette Jr., ancien sénateur, pour leurs réseaux politiques.

Dès le départ, Corcoran et La Follette ont fait pression auprès des républicains comme des démocrates, dans les deux chambres du Congrès, contre les politiques guatémaltèques – non pas en les présentant comme une menace pour les intérêts commerciaux de United Fruit, mais comme les éléments d’un complot communiste visant à détruire le capitalisme et les États-Unis.

Les efforts de la compagnie bananière ont porté leurs fruits en février 1949, lorsque plusieurs membres du Congrès ont dénoncé les réformes du droit du travail au Guatemala comme étant d’inspiration communiste. Le sénateur Claude Pepper a qualifié le code du travail de texte « manifestement et intentionnellement discriminatoire à l’égard de cette entreprise américaine » et d’« une mitrailleuse pointée sur la tête » de la United Fruit Company.

Deux jours plus tard, le membre de la Chambre des représentants John McCormack a repris mot pour mot cette déclaration, utilisant exactement les mêmes termes pour dénoncer les réformes. Les sénateurs Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Lister Hill et le représentant Mike Mansfield ont eux aussi pris position publiquement, en reprenant les éléments de langage figurant dans les notes internes de la United Fruit.

Aucun élu n’a prononcé un mot sur les bananes.

Lobbying et campagnes de propagande

Ce travail de lobbying, nourri par la rhétorique anticommuniste, a culminé cinq ans plus tard, lorsque le gouvernement américain a orchestré un coup d’État qui a renversé Árbenz lors d’une opération clandestine.

L’opération a débuté en 1953, lorsque l’administration Eisenhower a autorisé la CIA à lancer une campagne de guerre psychologique destinée à manipuler l’armée guatémaltèque afin de renverser le gouvernement démocratiquement élu. Des agents de la CIA ont alors soudoyé des membres de l’armée guatémaltèque tandis que des émissions de radio anticommunistes étaient diffusées et un discours, porté par les religieux et dénonçant un prétendu projet communiste visant à détruire l’Église catholique du pays, se propageait dans tout le Guatemala.

Parallèlement, les États-Unis ont armé des organisations antigouvernementales à l’intérieur du Guatemala et dans les pays voisins afin de saper davantage encore le moral du gouvernement Árbenz. La United Fruit a également fait appel au pionnier des relations publiques Edward Bernays pour diffuser sa propagande, non pas au Guatemala mais aux États-Unis. Bernays fournissait aux journalistes américains des rapports et des textes présentant le pays d’Amérique centrale comme une marionnette de l’Union soviétique.

Ces documents, dont un film intitulé « Why the Kremlin Hates Bananas », ont circulé grâce à des médias complaisants et à des membres du Congrès complices.

Détruire la révolution

En définitive – et les archives le démontrent –, l’action de la CIA a conduit des officiers de l’armée à renverser les dirigeants élus et à installer un régime plus favorable aux États-Unis, dirigé par Carlos Castillo Armas. Des Guatémaltèques opposés aux réformes ont massacré des responsables syndicaux, des responsables politiques et d’autres soutiens d’Árbenz et Arévalo. Selon des rapports officiels, au moins quarante-huit personnes sont mortes dans l’immédiat après-coup, tandis que des récits locaux font état de centaines de morts supplémentaires.

Pendant des décennies, le Guatemala s’est retrouvé aux mains de régimes militaires. De dictateur en dictateur, le pouvoir a réprimé brutalement toute opposition et instauré un climat de peur. Ces conditions ont contribué à des vagues d’émigration, comprenant d’innombrables réfugiés, mais aussi certains membres de gangs transnationaux.

Le retour de bâton

Afin d’étayer l’idée selon laquelle ce qui s’était produit au Guatemala n’avait rien à voir avec les bananes — conformément au discours de propagande de l’entreprise — l’administration Eisenhower a autorisé une procédure antitrust contre United Fruit, procédure qui avait été temporairement suspendue pendant l’opération afin de ne pas attirer davantage l’attention sur la société.

Ce fut le premier revers d’une longue série qui allait conduire au démantèlement de la United Fruit Company au milieu des années 1980. Après une succession de fusions, d’acquisitions et de scissions, ne demeure finalement que l’omniprésent logo de Miss Chiquita, apposé sur les bananes vendues par l’entreprise.

Et, selon de nombreux spécialistes des relations internationales, le Guatemala ne s’est jamais remis de la destruction de son expérience démocratique, brisée sous la pression des intérêts privés.

![]()

Les recherches d’Aaron Coy Moulton ont bénéficié de financements du Truman Library Institute, de Phi Alpha Theta, de la Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, du Roosevelt Institute, de l’Eisenhower Foundation, de la Massachusetts Historical Society, de la Bentley Historical Library, de l’American Philosophical Society, du Dirksen Congressional Center, de la Hoover Presidential Foundation et du Frances S. Summersell Center for the Study of the South.

– ref. Avant le pétrole vénézuelien, il y a eu les bananes du Guatemala… – https://theconversation.com/avant-le-petrole-venezuelien-il-y-a-eu-les-bananes-du-guatemala-273713