Source: The Conversation – USA – By Daniel Apai, Associate Dean for Research and Professor of Astronomy and Planetary Sciences, University of Arizona

On Jan. 11, 2026, I watched anxiously at the tightly controlled Vandenberg Space Force Base in California as an awe-inspiring SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carried NASA’s new exoplanet telescope, Pandora, into orbit.

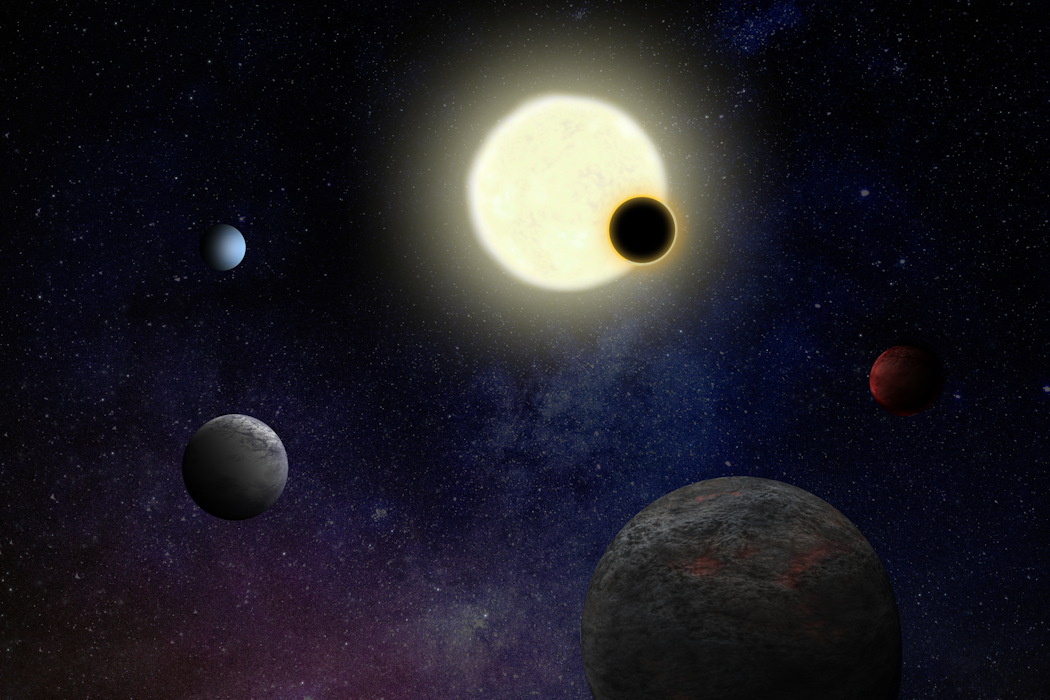

Exoplanets are worlds that orbit other stars. They are very difficult to observe because – seen from Earth – they appear as extremely faint dots right next to their host stars, which are millions to billions of times brighter and drown out the light reflected by the planets. The Pandora telescope will join and complement NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope in studying these faraway planets and the stars they orbit.

I am an astronomy professor at the University of Arizona who specializes in studies of planets around other stars and astrobiology. I am a co-investigator of Pandora and leading its exoplanet science working group. We built Pandora to shatter a barrier – to understand and remove a source of noise in the data – that limits our ability to study small exoplanets in detail and search for life on them.

Observing exoplanets

Astronomers have a trick to study exoplanet atmospheres. By observing the planets as they orbit in front of their host stars, we can study starlight that filters through their atmospheres.

These planetary transit observations are similar to holding a glass of red wine up to a candle: The light filtering through will show fine details that reveal the quality of the wine. By analyzing starlight filtered through the planets’ atmospheres, astronomers can find evidence for water vapor, hydrogen, clouds and even search for evidence of life. Researchers improved transit observations in 2002, opening an exciting window to new worlds.

For a while, it seemed to work perfectly. But, starting from 2007, astronomers noted that starspots – cooler, active regions on the stars – may disturb the transit measurements.

In 2018 and 2019, then-Ph.D. student Benjamin V. Rackham, astrophysicist Mark Giampapa and I published a series of studies showing how darker starspots and brighter, magnetically active stellar regions can seriously mislead exoplanets measurements. We dubbed this problem “the transit light source effect.”

Most stars are spotted, active and change continuously. Ben, Mark and I showed that these changes alter the signals from exoplanets. To make things worse, some stars also have water vapor in their upper layers – often more prominent in starspots than outside of them. That and other gases can confuse astronomers, who may think that they found water vapor in the planet.

In our papers – published three years before the 2021 launch of the James Webb Space Telescope – we predicted that the Webb cannot reach its full potential. We sounded the alarm bell. Astronomers realized that we were trying to judge our wine in light of flickering, unstable candles.

The birth of Pandora

For me, Pandora began with an intriguing email from NASA in 2018. Two prominent scientists from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Elisa Quintana and Tom Barclay, asked to chat. They had an unusual plan: They wanted to build a space telescope very quickly to help tackle stellar contamination – in time to assist Webb. This was an exciting idea, but also very challenging. Space telescopes are very complex, and not something that you would normally want to put together in a rush.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Conceptual Image Lab, CC BY

Pandora breaks with NASA’s conventional model. We proposed and built Pandora faster and at a significantly lower cost than is typical for NASA missions. Our approach meant keeping the mission simple and accepting somewhat higher risks.

What makes Pandora special?

Pandora is smaller and cannot collect as much light as its bigger brother Webb. But Pandora will do what Webb cannot: It will be able to patiently observe stars to understand how their complex atmospheres change.

By staring at a star for 24 hours with visible and infrared cameras, it will measure subtle changes in the star’s brightness and colors. When active regions in the star rotate in and out of view, and starspots form, evolve and dissipate, Pandora will record them. While Webb very rarely returns to the same planet in the same instrument configuration and almost never monitors their host stars, Pandora will revisit its target stars 10 times over a year, spending over 200 hours on each of them.

With that information, our Pandora team will be able to figure out how the changes in the stars affect the observed planetary transits. Like Webb, Pandora will observe the planetary transit events, too. By combining data from Pandora and Webb, our team will be able to understand what exoplanet atmospheres are made of in more detail than ever before.

After the successful launch, Pandora is now circling Earth about every 90 minutes. Pandora’s systems and functions are now being tested thoroughly by Blue Canyon Technologies, Pandora’s primary builder.

About a week after launch, control of the spacecraft will transition to the University of Arizona’s Multi-Mission Operation Center in Tucson, Arizona. Then the work of our science teams begins in earnest and we will begin capturing starlight filtered through the atmospheres of other worlds – and see them with a new, steady eye.

![]()

Daniel Apai is a professor of astronomy, planetary sciences and optical science at the University of Arizona. He receives funding from NASA.

– ref. NASA’s Pandora telescope will study stars in detail to learn about the exoplanets orbiting them – https://theconversation.com/nasas-pandora-telescope-will-study-stars-in-detail-to-learn-about-the-exoplanets-orbiting-them-272155