Source: The Conversation – UK – By Kelly Fincham, Programme director, BA Global Media, Lecturer media and communications, University of Galway

When you spot false or misleading information online, or in a family group chat, how do you respond? For many people, their first impulse is to factcheck – reply with statistics, make a debunking post on social media or point people towards trustworthy sources.

Factchecking is seen as a go-to method for tackling the spread of false information. But it is notoriously difficult to correct misinformation.

Evidence shows readers trust journalists less when they debunk, rather than confirm, claims. Factchecking can also result in repeating the original lie to a whole new audience, amplifying its reach.

The work of media scholar Alice Marwick can help explain why factchecking often fails when used in isolation. Her research suggests that misinformation is not just a content problem, but an emotional and structural one.

She argues that it thrives through three mutually reinforcing pillars: the content of the message, the personal context of those sharing it, and the technological infrastructure that amplifies it.

1. The message

People find it cognitively easier to accept information than to reject it, which helps explain why misleading content spreads so readily.

Misinformation, whether in the form of a fake video or misleading headline, is problematic only when it finds a receptive audience willing to believe, endorse or share it. It does so by invoking what American sociologist Arlie Hochschild calls “deep stories”. These are emotionally resonant narratives that can explain people’s political beliefs.

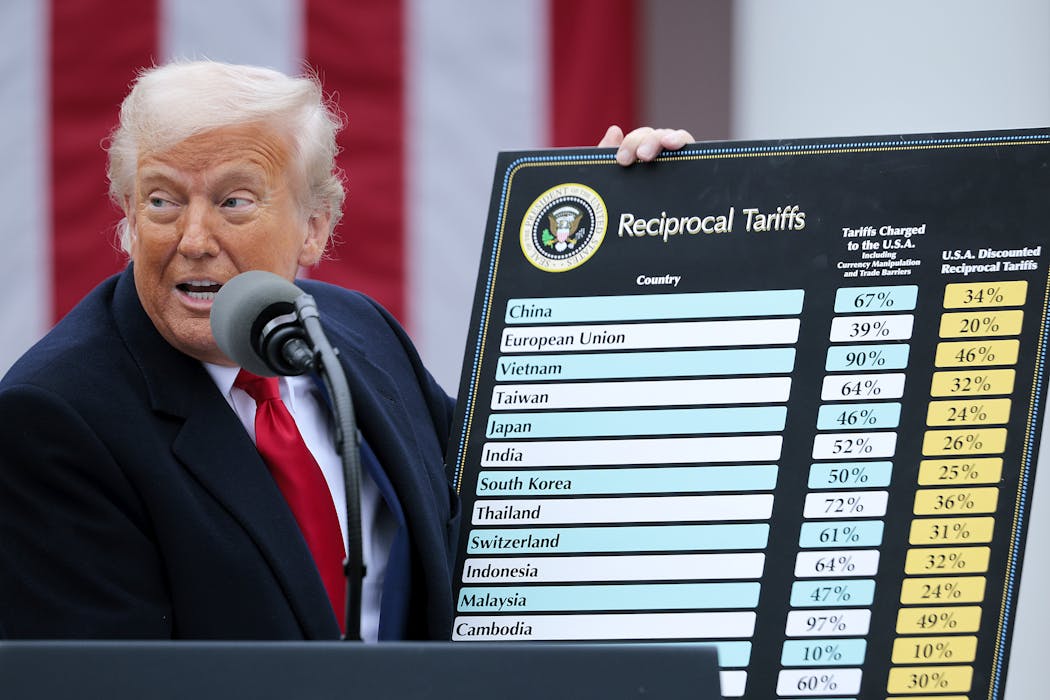

The most influential misinformation or disinformation plays into existing beliefs, emotions and social identities, often reducing complex issues to familiar emotional narratives. For example, disinformation about migration might use tropes of “the dangerous outsider”, “the overwhelmed state” or “the undeserving newcomer”.

2. Personal context

When fabricated claims align with a person’s existing values, beliefs and ideologies, they can quickly harden into a kind of “knowledge”. This makes them difficult to debunk.

Marwick researched the spread of fake news during the 2016 US presidential election. One source described how her strongly conservative mother continued to share false stories about Hillary Clinton, even after she (the daughter) repeatedly debunked the claims.

The mother eventually said: “I don’t care if it’s false, I care that I hate Hillary Clinton, and I want everyone to know that!” This neatly encapsulates how sharing or posting misinformation can be an identity-signalling mechanism.

Ekateryna Zubal/Shutterstock

People share false claims to signal in-group allegiance, a phenomenon researchers describe as “identity-based motivation”. The value of sharing lies not in providing accurate information, but in serving as social currency that reinforces group identity and cohesion.

The increase in the availability of AI-generated images will escalate the spread further. We know that people are willing to share images that they know are fake, when they believe they have an “emotional truth”. Visual content carries an inherent credibility and emotional force – “a picture is worth a thousand words” – that can override scepticism.

3. Technical structures

All of the above is supported by the technical structures of social media platforms, which are engineered to reward engagement. These platforms create revenue by capturing and selling users’ attention to advertisers. The longer and more intensively people engage with content, the more valuable that engagement becomes for advertisers and platform revenue.

Metrics such as time spent, likes, shares and comments are central to this business model. Recommendation algorithms are therefore explicitly optimised to maximise user engagement. Research shows that emotionally charged content – especially content that evokes anger, fear or outrage – generates significantly more engagement than neutral or positive content.

While misinformation clearly thrives in this environment, the sharing function of messaging and social media apps enables it to spread further. In 2020, the BBC reported that a single message sent to a WhatsApp group of 20 people could ultimately reach more than 3 million people, if each member shared it with another 20 people and the process was repeated five times.

By prioritising content likely to be shared and making sharing effortless, every like, comment or forward feeds the system. The platforms themselves act as a multiplier, enabling misinformation to spread faster, farther and more persistently than it could offline.

Read more:

The dynamics that polarise us on social media are about to get worse

Factchecking fails not because it is inherently flawed, but because it is often deployed as a short-term solution to the structural problem of misinformation.

Meaningfully addressing it therefore requires a response that addresses all three of these pillars. It must involve long-term changes to incentives and accountability for tech platforms and publishers. And it requires shifts in social norms and awareness of our own motivations for sharing information.

If we continue to treat misinformation as a simple contest between truth and lies, we will keep losing. Disinformation thrives not just on falsehoods, but on the social and structural conditions that make them meaningful to share.

![]()

Kelly Fincham does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why people believe misinformation even when they’re told the facts – https://theconversation.com/why-people-believe-misinformation-even-when-theyre-told-the-facts-271236