Source: The Conversation – UK – By Adrian Palmer, Senior Lecturer, Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London

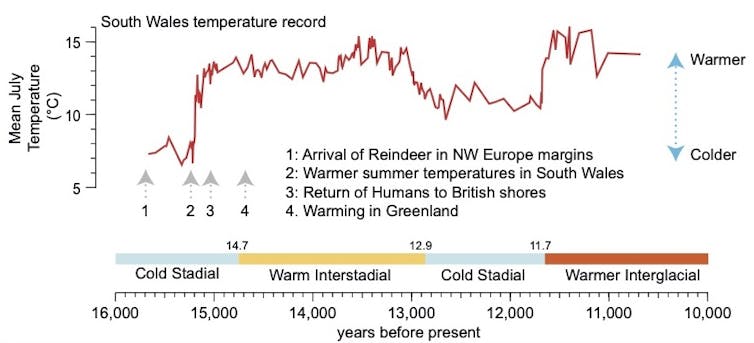

The return of humans to the British Isles after the end of the last ice sheet, which covered much of the northern hemisphere, happened around 15,200 years ago – nearly 500 years earlier than previous estimates.

This movement of people coincided with a sharp rise in summer temperatures in southern Britain, research by our group shows.

These environmental conditions allowed humans to migrate back up into Britain – then still connected to the European mainland. They were hunting herds of reindeer and horses, which were migrating northwards into ecosystems that supported their preferred food for grazing.

After the end of the last ice age, the climate in north-west Europe shifted from cold to warm conditions on at least two occasions, with changes in temperature thought to have occurred over decades.

Our latest research addresses the first of these transitions in the Late Upper Palaeolithic period (14,000 to 11,000 years ago). In areas such as north-west Europe, including where the British Isles are today, humans successively abandoned and then returned to areas at the abrupt transitions between cold and warm periods.

Broadly, evidence of humans from fossil records showed them migrating to where the environmental conditions supported their survival.

Reasons for repopulation

The repopulation of the British Isles after the last ice age is an excellent period to explore the relationships between climate and environment, and the reappearance of humans in this region.

In previous studies, the evidence has been somewhat difficult to read due to uncertainty of the dating methods and incomplete records of environmental and climate conditions. The traditional view had been that the north-west European climate warmed from ice-age temperatures around 14,700 years ago, and humans reoccupied Britain at that time.

However, revised preparation techniques in the early 2000s for the dating of human remains and associated artefacts showed the earliest appearance of humans occurred prior to the warming of 14,700 years ago.

This finding was difficult to understand, as it coincided with what were then considered cold glacial climates that would have been unlikely to support the resources people needed to survive in Britain.

Summer climate record from Llangorse Lake, Wales

Author’s own illustration

Our study used new calibrations of radiocarbon ages that confirmed the age of those human remains to between 15,200 and 15,000 years ago. So, if humans really were present in the British Isles, could they have survived in cold climates – or was our picture of past environments at this time incorrect?

Clearer insight came from Llangorse Lake (Lake Syffadan) in south Wales, where the lake sediments spanning the last 19,000 years record the abrupt climate change in detail. In addition, the lake’s location lies close to the cave in the Wye Valley where the earliest British evidence for human remains after the ice age were found.

By extracting fossil pollen, chironomids (non-biting midges) and chemical analysis of the lake sediments, an unexpected picture of the climate emerged – one that showed previous climate reconstructions for the region were incorrect.

The chironomids were used to reconstruct summer temperature, and this showed the climate warmed in a different pattern than has been identified in other parts of north-west Europe and Greenland. An abrupt temperature shift from 5–7°C to 10–14°C occurred at 15,200 years in Britain – 500 years earlier than previous evidence had suggested.

Just prior to this climate warming, the presence of human prey, such as reindeer and horses, is more consistently detected in southern Britain around 15,500 years ago. These animals were exploiting the newly available grazing grounds, with people tracking the herds northwards and enduring the moderately warmer summer climatic conditions.

Examining archaeological records along with environmental and climatic archives allows more precise reconstructions of when humans were able to repopulate previously inhospitable regions. This is helped by re-evaluating old radiocarbon dates of human evidence in the landscape, and by generating more precise environmental records from the time – including more precise timings of the transitions from cold to warm periods.

This provided us with a fuller picture of human responses to changes in temperature (and their impact on the environment) in the Late Upper Palaeolithic period. Human survival was the driver of these movements, and following prey into new areas was important. But only a relatively small change in summer temperatures was required to enable this migration.

Our research provides better understanding of human behaviour and resilience to climate change after the last ice age around 15,000 years ago. But understanding these environmental triggers from the past helps create new perspectives on human responses to them even now.

These basic factors have not gone away. The response observed in this study might provide clues on future human behaviour as our polar regions warm and glaciers melt, showing how the potential for human migration could be increased.

![]()

Adrian Palmer receives funding from Natural Environment Research Council. He is affiliated with Royal Holloway, University of London and Quaternary Research Association.

– ref. Humans returned to British Isles earlier than previously thought at the end of the last ice age – https://theconversation.com/humans-returned-to-british-isles-earlier-than-previously-thought-at-the-end-of-the-last-ice-age-271242