Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Basema Al-Alami, SJD Candidate, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto

British Columbia Premier David Eby recently called on Prime Minister Mark Carney to designate the India-based Bishnoi gang a terrorist organization.

Brampton Mayor Patrick Brown echoed the request days later. The RCMP has also alleged the gang may be targeting pro-Khalistan activists in Canada.

These claims follow a series of high-profile incidents in India linked to the Bishnoi network, including the murder of a Punjabi rapper in New Delhi, threats against a Bollywood actor and the killing of a Mumbai politician in late 2024.

How terrorism designations work

Eby’s request raises broader legal questions. What does it mean to label a group a terrorist organization in Canada and what happens once that label is applied?

Under Section 83.05 of the Criminal Code, the federal government can designate an entity a terrorist organization if there are “reasonable grounds to believe” it has engaged in, supported or facilitated terrorist activity. The term “entity” is defined broadly, covering individuals, groups, partnerships and unincorporated associations.

The process begins with intelligence and law enforcement reports submitted to the public safety minister, who may then recommend listing the group to cabinet if it’s believed the legal threshold is met. If cabinet agrees, the group is officially designated a terrorist organization.

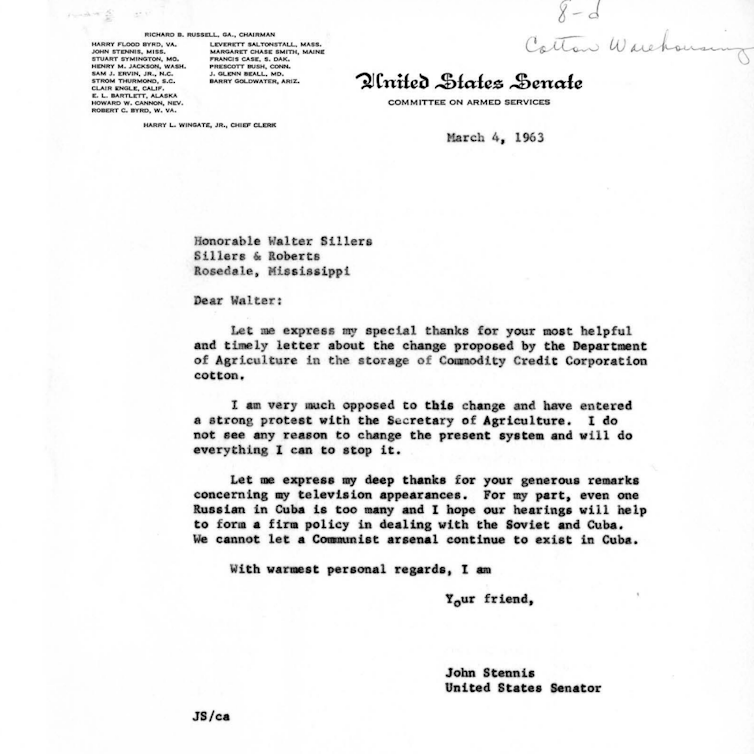

A designation carries serious consequences: assets can be frozen and financial dealings become criminalized. Banks and other institutions are protected from liability if they refuse to engage with the group. Essentially, the designation cuts the group off from economic and civic life, often without prior notice or public hearing.

As of July 2025, Canada has listed 86 entities, from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to far-right and nationalist organizations. In February, the government added seven violent criminal groups from Latin America, including the Sinaloa cartel and La Mara Salvatrucha, known as the MS-13.

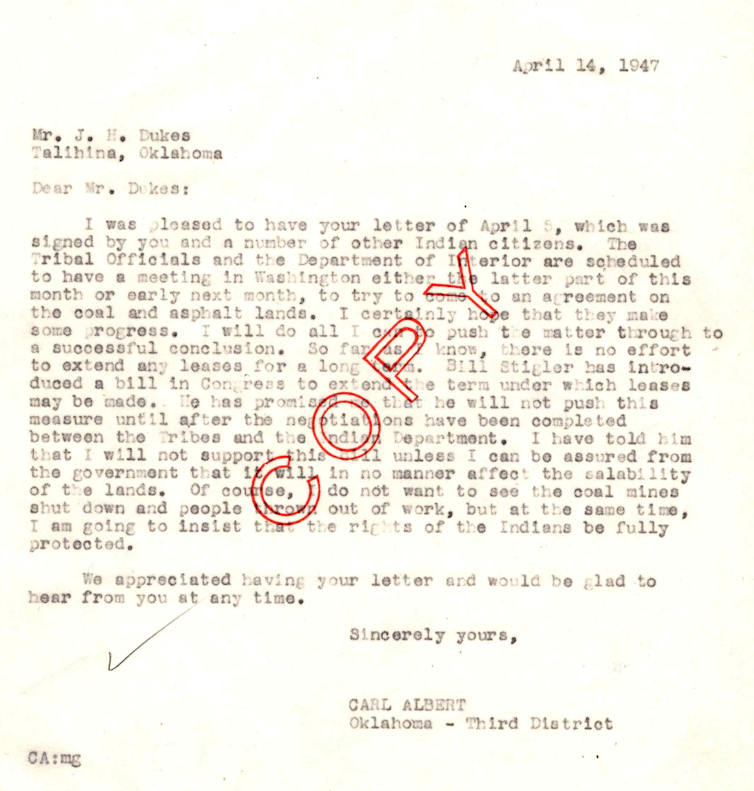

This marked a turning point: for the first time, Canada extended terrorism designations beyond ideological or political movements to include transnational criminal networks.

Why the shift matters

This shift reflects a deeper redefinition of what Canada considers a national security threat. For much of the post-9/11 era, counterterrorism efforts in Canada have concentrated on groups tied to ideological, religious or political agendas — most often framed through the lens of Islamic terrorism.

This has determined not only who is targeted, but also what forms of violence are taken seriously as national security concerns.

That is why the recent expansion of terrorism designations — first with the listing of Mexican cartels in early 2025, and now potentially with the Bishnoi gang — feels so significant.

It signals a shift away from targeting ideology alone and toward labelling profit-driven organized crime as terrorism. While transnational gangs may pose serious public safety risks, designating them terrorist organizations could erode the legal and political boundaries that once separated counterterrorism initiatives from criminal law.

Canada’s terrorism listing process only adds to these concerns. The decision is made by cabinet, based on secret intelligence, with no obligation to inform the group or offer a chance to respond. Most of the evidence remains hidden, even from the courts.

While judicial review is technically possible, it is limited, opaque and rarely successful.

In effect, the label becomes final. It brings serious legal consequences like asset freezes, criminal charges and immigration bans. But the informal fallout can be just as harsh: banks shut down accounts, landlords back out of leases, employers cut ties. Even without a trial or conviction, the stigma of being associated with a listed group can dramatically change someone’s life.

What’s at stake

Using terrorism laws to go after violent criminal networks like the Bishnoi gang may seem justified. But it quietly expands powers that were originally designed for specific types of threats. It also stretches a national security framework already tainted by racial and political bias.

Read more:

Canadian law enforcement agencies continue to target Muslims

For more than two decades, Canada’s counterterrorism laws have disproportionately targeted Muslim and racialized communities under a logic of pre-emptive suspicion. Applying those same powers to organized crime, especially when it impacts immigrant and diaspora communities, risks reproducing that harm under a different label.

Canadians should be asking: what happens when tools built for exceptional threats become the default response to complex criminal violence?

As the federal government considers whether to label the Bishnoi gang a terrorist organization, the real question goes beyond whether the group meets the legal test. It’s about what kind of legal logic Canada is endorsing.

Terrorism designations carry sweeping powers, with little oversight and lasting consequences. Extending those powers to organized crime might appear pragmatic, but it risks normalizing a process that has long operated in the shadows, shaped by secrecy and executive discretion.

As national security law expands, Canadians should ask not just who gets listed, but how those decisions are made and what broader political agendas they might serve.

![]()

Basema Al-Alami does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Calls to designate the Bishnoi gang a terrorist group shine a spotlight on Canadian security laws – https://theconversation.com/calls-to-designate-the-bishnoi-gang-a-terrorist-group-shine-a-spotlight-on-canadian-security-laws-259844