Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Nicole Rinehart, Nicole Rinehart, Professor, Clinical Psychology, Director of the Neurodevelopment Program, School of Psychological Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects how people’s brains develop and function, impacting behaviour, communication and socialising. It can also involve differences in the way you move and walk – known as your “gait”.

Having an “odd gait” is now listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a supporting diagnostic feature of autism.

What does this look like?

The most noticeable gait differences among autistic people are:

- toe-walking, walking on the balls of the feet

- in-toeing, walking with one or both feet turned inwards

- out-toeing, walking with one or both feet turned out.

Research has also identified more subtle differences. A study summarising 30 years of research among autistic people reports that gait is characterised by:

- walking more slowly

- taking wider steps

- spending longer in the “stance” phase, when the foot leaves the ground

- taking more time to complete each step.

Autistic people show much more personal variability in the length and speed of their strides, as well as their walking speed.

Gait differences also tend to occur alongside other motor differences, such as issues with balance, coordination, postural stability and handwriting. Autistic people may need support for these other motor skills.

What causes gait differences?

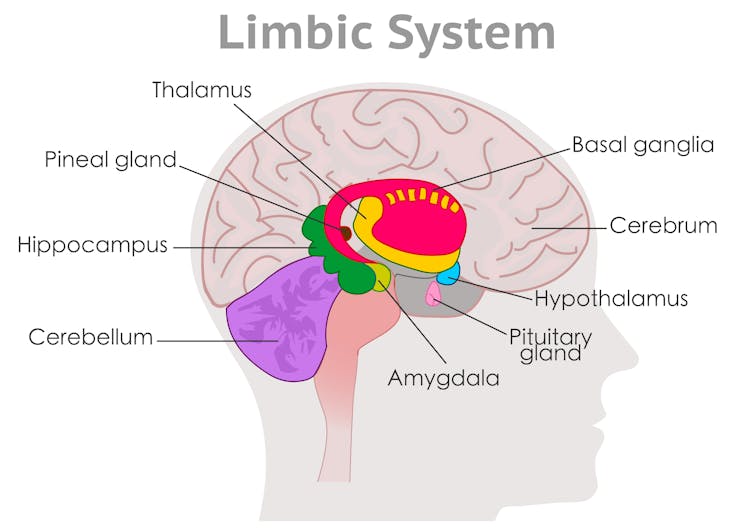

These are largely due to differences in brain development, specifically in areas known as the basal ganglia and cerebellum.

The basal ganglia are broadly responsible for sequencing movement including through shifting posture. It ensures your gait appears effortless, smooth and automatic.

The cerebellum then uses visual and proprioceptive information (to sense the body’s position and movement) to adjust and time movements to maintain postural stability. It ensures movement is controlled and coordinated.

grayjay/Shutterstock

Developmental differences in these brain regions relate to the way the areas look (their structure), how they work (their function and activation) and how they “speak” to other areas of the brain (their connections).

While some researchers have suggested that autistic gait occurs due to delayed development, we now know gait differences persist across the lifespan. Some differences actually become clearer with age.

In addition to brain-based differences, the autistic gait is also associated with factors such as the person’s broader motor, language and cognitive capabilities.

People with more complex support needs might have more pronounced gait or motor differences, together with language and cognitive difficulties.

Motor dysregulation might indicate sensory or cognitive overload and be a useful marker that the person might benefit from extra support or a break.

How is it managed?

Not all differences need to be treated. Instead, clinicians take an individualised and goals-based approach.

Some autistic people might have subtle gait differences that are observable during testing. But if these differences don’t impact a person’s ability to participate in everyday life, they don’t require support.

An autistic person is likely to benefit from support for gait differences if they have a functional impact on their daily life. This might include:

- increased risk of, or frequent, falls

- difficulty participating in the physical activities they enjoy

- physical consequences such as tightness of the Achilles and calf muscles, or associated pain in other areas, such as the feet or back.

Some children may also benefit from support for motor skill development. However this doesn’t have to occur in a clinic.

Given children spend a large portion of their time at school, programs that integrate opportunities for movement throughout the school day allow autistic children to develop motor skills outside of the clinic and alongside peers. We developed the Joy of Moving Program in Australia, for example, which gets students moving in the classroom.

Our community-based intervention studies show autistic children’s movement abilities can improve after engaging in community-based interventions, such as sports or dance.

Community-based support models empower autistic children to have agency in how they move, rather than seeing different ways of moving as a problem to be fixed.

Where to from here?

While we have learnt a lot about autistic gait at a broad level, researchers and clinicians are still seeking a better understanding of why and when individual variability occurs.

We’re also still determining how to best support individual movement styles, including among children as they develop.

However there is growing evidence that physical activity enhances social skills and behavioural regulation in preschool children with autism.

So it’s encouraging that states and territories are moving towards more community-based foundational supports for autistic children and their peers, as governments develop supports outside the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The authors thank the late Emeritus Professor John Bradshaw for his early input into this piece.

![]()

Nicole Rinehart receives funding from: Moose Happy Kids Foundation, MECCA M-Power, the Grace & Emilio Foundation, Ferrero Australia, as part of the global Kinder Joy of moving program, Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd, Jonathan and Simone Wenig, Adam Krongold, the Grosman Family Foundation, the Shoreline Foundation, the Victorian Department of Education, the NSW Department of Education, and the Department of Social Services – Information, Linkages and Capacity Building (ILC) Program, and has worked in partnership with the Australian Football League.

Chloe Emonson works on projects that receive funding from: Moose Happy Kids Foundation, MECCA M-Power, the Grace & Emilio Foundation, Ferrero Australia, as part of the global Kinder Joy of moving program, Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd, Jonathan and Simone Wenig, Adam Krongold, the Grosman Family Foundation, the Shoreline Foundation, the Victorian Department of Education, the NSW Department of Education, and the Department of Social Services – Information, Linkages and Capacity Building (ILC) Program, and has worked in partnership with the Australian Football League.

Ebony Lindor works on projects that receive funding from: Moose Happy Kids Foundation, MECCA M-Power, the Grace & Emilio Foundation, Ferrero Australia, as part of the global Kinder Joy of moving program, Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd, Jonathan and Simone Wenig, Adam Krongold, the Grosman Family Foundation, the Shoreline Foundation, the Victorian Department of Education, the NSW Department of Education, and the Department of Social Services – Information, Linkages and Capacity Building (ILC) Program, and has worked in partnership with the Australian Football League.

– ref. Why do some autistic people walk differently? – https://theconversation.com/why-do-some-autistic-people-walk-differently-231685