Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Paul Mwebaze, Research Economist at the Institute for Sustainability, Energy and Environment, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Drive through the plains of Iowa or Kansas and you’ll see more than rows of corn, wheat and soybeans. You’ll also see towering wind turbines spinning above fields and solar panels shining in the sun on barns and machine sheds.

For many farmers, these are lifelines. Renewable energy provides steady income and affordable power, helping farms stay viable when crop prices fall or drought strikes.

But some of that opportunity is now at risk as the Trump administration cuts federal support for renewable energy.

Wind power brings steady income for farms

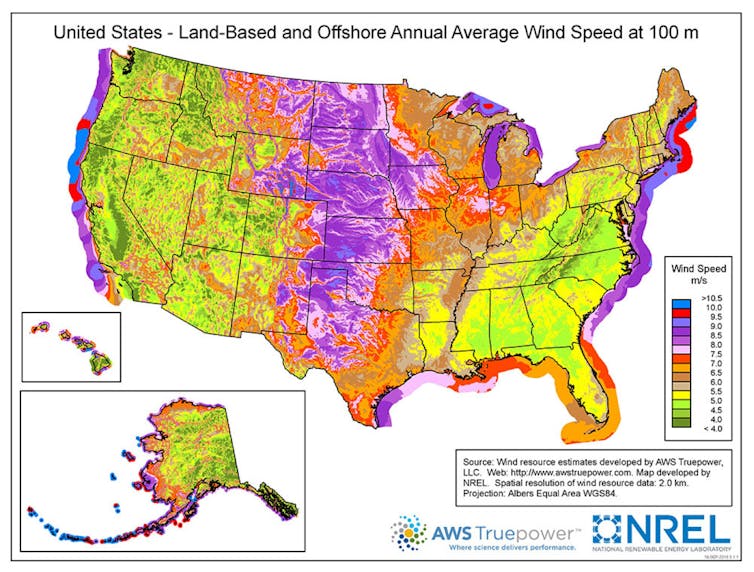

Wind energy is a significant economic driver in rural America. In Iowa, for example, over 60% of the state’s electricity came from wind energy in 2024, and the state is a hub for wind turbine manufacturing and maintenance jobs.

For landowners, wind turbines often mean stable lease payments. Those historically were around US$3,000 to $5,000 per turbine per year, with some modern agreements $5,000 to $10,000 annually, secured through 20- to 30-year contracts.

Nationwide, wind and solar projects contribute about $3.5 billion annually in combined lease payments and state and local taxes, more than a third of it going directly to rural landowners.

NREL

These figures are backed by long-term contracts and multibillion‑dollar annual contributions, reinforcing the economic value that turbines bring to rural landowners and communities.

Wind farms also contribute to local tax revenues that help fund rural schools, roads and emergency services. In counties across Texas, wind energy has become one of the most significant contributors to local property tax bases, stabilizing community budgets and helping pay for public services as agricultural commodity revenues fluctuate.

In Oldham County in northwest Texas, for example, clean energy projects provided 22% of total county revenues in 2021. In several other rural counties, wind farms rank among the top 10 property taxpayers, contributing between 38% and 69% of tax revenue.

The construction and operation of these projects also bring local jobs in trucking, concrete work and electrical services, boosting small-town businesses.

Andrew Marszal/AFP via Getty Images

The U.S. wind industry supports over 300,000 U.S. jobs across construction, manufacturing, operations and other roles connected to the industry, according to the American Clean Power Association.

Renewable energy has been widely expected to continue to grow along with rising energy demand. In 2024, 93% of all new electricity generating capacity was wind, solar or energy storage, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration expected a similar percentage in 2025 as of June.

Solar can cut power costs on the farm

Solar energy is also boosting farm finances. Farmers use rooftop panels on barns and ground-mounted systems to power irrigation pumps, grain dryers and cold storage facilities, cutting their power costs.

Some farmers have adopted agrivoltaics – dual-use systems that grow crops beneath solar panels. The panels provide shade, helping conserve water, while creating a second income path. These projects often cultivate pollinator-friendly plants, vegetables such as lettuce and spinach, or even grasses for grazing sheep, making the land productive for both food and energy.

Federal grants and tax credits that were significantly expanded under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act helped make the upfront costs of solar installations affordable.

Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

However, the federal spending bill signed by President Donald Trump on July 4, 2025, rolled back many clean energy incentives. It phases down tax credits for distributed solar projects, particularly those under 1 megawatt, which include many farm‑scale installations, and sunsets them entirely by 2028. It also eliminates bonus credits that previously supported rural and low‑income areas.

Without these credits, the upfront cost of solar power could be out of reach for some farmers, leaving them paying higher energy costs. At a 2024 conference organized by the Institute of Sustainability, Energy and Environment at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where I work as a research economist, farmers emphasized the importance of tax credits and other economic incentives to offset the upfront cost of solar power systems.

What’s being lost

The cuts to federal incentives include terminating the Production Tax Credit for new projects placed in service after Dec. 31, 2027, unless construction begins by July 4, 2026, and is completed within a tight time frame. The tax credit pays eligible wind and solar facilities approximately 2.75 cents per kilowatt-hour over 10 years, effectively lowering the cost of renewable energy generation. Ending that tax credit will likely increase the cost of production, potentially leading to higher electricity prices for consumers and fewer new projects coming online.

The changes also accelerate the phase‑out of wind power tax credits. Projects must now begin construction by July 4, 2026, or be in service before the end of 2027 to qualify for any credit.

Meanwhile, the Investment Tax Credit, which covers 30% of installed cost for solar and other renewables, faces similar limits: Projects must begin by July 4, 2026, and be completed by the end of 2027 to claim the credits. The bill also cuts bonuses for domestic components and installations in rural or low‑income locations. These adjustments could slow new renewable energy development, particularly smaller projects that directly benefit rural communities.

While many existing clean energy agreements will remain in place for now, the rollback of federal incentives threatens future projects and could limit new income streams. It also affects manufacturing and jobs in those industries, which some rural communities rely on.

Renewable energy also powers rural economies

Renewable energy benefits entire communities, not just individual farmers.

Wind and solar projects contribute millions of dollars in tax revenue. For example, in Howard County, Iowa, wind turbines generated $2.7 million in property tax revenue in 2024, accounting for 14.5% of the county’s total budget and helping fund rural schools, public safety and road improvements.

In some rural counties, clean energy is the largest new source of economic activity, helping stabilize local economies otherwise reliant on agriculture’s unpredictable income streams. These projects also support rural manufacturing – such as Iowa turbine blade factories like TPI Composites, which just reopened its plant in Newton, and Siemens Gamesa in Fort Madison, which supply blades for GE and Siemens turbines. The tax benefits in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act helped boost those industries – and the jobs and local tax revenue they bring in.

On the solar side, rural companies like APA Solar Racking, based in Ohio, manufacture steel racking systems for utility-scale solar farms across the Midwest.

As rural America faces economic uncertainty and climate pressures, I believe homegrown renewable energy offers a practical path forward. Wind and solar aren’t just fueling the grid; they’re helping keep farms and rural towns alive.

![]()

The Sustainably Co-locating Agricultural and Photovoltaic Electricity Systems (SCAPES) project, led by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

– ref. How wind and solar power helps keep America’s farms alive – https://theconversation.com/how-wind-and-solar-power-helps-keep-americas-farms-alive-260657