Source: The Conversation – UK – By Maria Pertl, Lecturer in Psychology, Department of Health Psychology, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences

By 2030, an estimated 47 million women worldwide will enter menopause each year. The transition through menopause can last several years and brings with it a host of physical, mental and brain changes. One of the most distressing symptoms reported by women is “brain fog”.

This umbrella term refers to difficulties with memory, concentration and mental clarity. Women may find themselves forgetting words, names or appointments, or misplacing items. While these symptoms can be alarming, they usually resolve after menopause and are not a sign of dementia.

Hormonal fluctuations, particularly declining oestrogen levels, are a key driver of cognitive changes during the menopause transition. But it’s not just hormones. Hot flushes, night sweats, poor sleep and low mood all contribute to cognitive difficulties. The good news? Many of the contributing factors are modifiable. That’s where lifestyle medicine comes in.

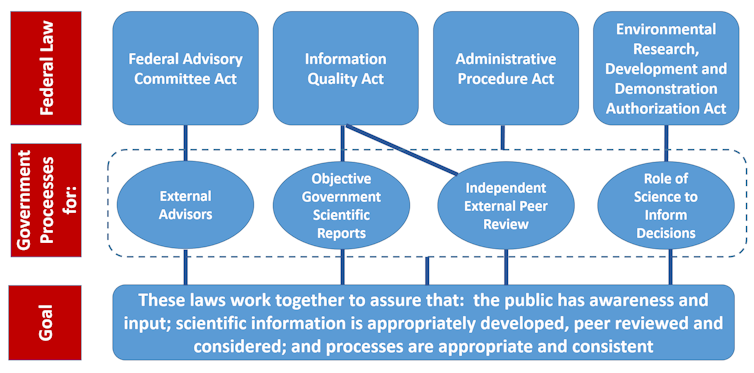

Lifestyle medicine is an evidence-based approach that uses lifestyle interventions to prevent and manage chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and dementia. It focuses on six pillars: sleep, physical activity, nutrition, stress management, social connection and avoidance of harmful substances. These same pillars can also support cognitive health during menopause.

Sleep is an underestimated factor in brain health — it is essential for memory consolidation and brain repair. Yet one in three women going through menopause experience significant sleep disturbance. Hot flashes, anxiety, and hormonal changes can all disrupt sleep, creating a vicious cycle that worsens brain fog.

Improving sleep hygiene can help. This includes avoiding caffeine late in the day, reducing screen time before bed, keeping a consistent sleep schedule and maintaining a cool bedroom. Physical activity during the day – especially outside in the morning – also supports better sleep.

Physical activity is one of the most powerful tools for brain health. It improves blood flow to the brain, reduces inflammation and increases the size of the hippocampus (the brain’s memory centre). It also helps regulate mood, improve sleep and support cardiovascular and metabolic health. For menopausal women, it has the added benefit of improving bone health, sexual function and maintaining a healthy weight.

The World Health Organization recommends at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, plus two sessions of muscle-strengthening exercises. Even brisk walking can make a difference.

Stress can make it difficult to think clearly and chronic stress may accelerate brain ageing through chronically elevated cortisol levels. Menopause can be a stressful time, especially when cognitive changes affect sleep, confidence and daily functioning.

Mindfulness, yoga, tai chi and breathing exercises can help reduce stress and improve focus. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), a form of talking therapy, is also effective in addressing negative thought patterns and improving coping strategies. Finding a hobby that brings joy or a sense of “flow” can also be a powerful stress reliever.

What we eat plays a crucial role in brain health. The Mediterranean diet — rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil and fish — has been linked to better memory and reduced risk of cognitive decline.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish and flaxseeds, are particularly beneficial for brain function. Avoiding ultra-processed foods, added sugars and trans fats can help reduce inflammation and stabilise energy levels.

Social connection is a powerful yet often overlooked pillar of lifestyle medicine that has substantial effects on physical, mental and brain health. During menopause, women may feel less able to participate in social activities and experience increased isolation or changes in relationships, which can negatively affect mood and cognition.

Strong social ties stimulate the brain, support emotional regulation, and buffer against stress. Quality matters more than quantity. Regular check-ins with friends, joining a club, volunteering, or even brief positive interactions can all make a difference.

Alcohol and other substances can have a circular effect on sleep, mood, and cognition. While alcohol may initially feel relaxing, it disrupts sleep quality and can worsen anxiety and memory issues.

Reducing alcohol and avoiding tobacco and recreational drugs can improve sleep, mood and cognitive clarity. If cutting back feels difficult, seeking support from a healthcare professional or support group can be a helpful first step.

Making lifestyle changes can feel overwhelming, especially when you’re already feeling tired or stressed. Financial pressures or personal circumstances can make lifestyle changes feel out of reach. Start small. Make just one change in one pillar, such as sticking to a regular bedtime or adding a short daily walk, and build from there. Small, consistent steps can make a big difference to clearing brain fog.

Menopausal brain fog is real, but it’s also manageable. By focusing on the six pillars of lifestyle medicine, women can take proactive steps to support their cognitive health and overall wellbeing during this important life transition.

![]()

Maria Pertl receives research funding from the Irish Cancer Society and the National Cancer Control Programme. She is a committee member of the Irish Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

Lisa Mellon co-founded the Irish Society for Lifestyle Medicine.

– ref. Menopause and brain fog: why lifestyle medicine could make a difference – https://theconversation.com/menopause-and-brain-fog-why-lifestyle-medicine-could-make-a-difference-261683