Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Mollie J. Cohen, Associate Professor of Political Science, Purdue University

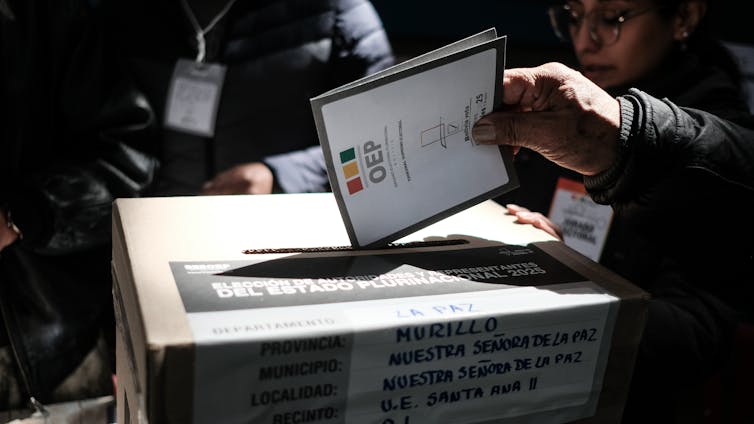

For the first time since the country’s return to democracy in 1982, Bolivia’s presidential election will go to a runoff after no candidate secured the required absolute majority in the first-round vote on Aug. 17, 2025.

The choice Bolivians now face means that the country is set to elect a non-left-wing candidate for the first time in a generation. In October, they will choose between the center-right Sen. Rodrigo Paz Pereira, who led the first round with approximately 32% of the valid vote, and former right-wing interim President Jorge “Tuto” Quiroga, who had close to 27%.

As many predicted, the left lost spectacularly, with the best-performing leftist candidate, Andrónico Rodríguez, winning only around 8% of the valid vote.

In fact, the left performed so poorly that its vote count was surpassed by invalid ballots. More than 19% of all ballots were spoiled and an additional 2.5% left blank. Indeed, the invalid vote roughly quadrupled compared to presidential elections between 2006 and 2020, when only about 5% of ballots were invalid.

Invalid votes are those that have been left unmarked – “blank” votes – or mismarked – “null” or “spoiled” votes – so that a voter’s intent is unclear. They are usually counted but excluded from official electoral math. But as I document in my 2024 book, “None of the Above,” blank and spoiled votes are also one of the most widely used tools of protest in Latin American democracies. Every year, millions of voters use the tactic to express their frustration with the candidates on the ballot, while at the same time demonstrating their commitment to democracy and elections.

In the case of Bolivia, I believe the rise in invalid votes is both a symptom of widespread dissatisfaction with the political and economic status quo and a signal of persistent, but not overwhelming, support for the divisive former president, Evo Morales.

Jorge Mateo Romay Salinas/Anadolu via Getty Images

Political and economic crisis

Bolivia’s presidential election took place as the country experiences dual economic and political crises. Like many of its neighbors, Bolivia experienced a commodity-driven economic boom at the beginning of the 21st century, fueled in this case by the export of lithium and natural gas. However, boom turned to bust in the 2010s as global commodity prices plunged. With its currency pegged to the U.S. dollar and a heavy reliance on gas exports, Bolivia’s economy suffered.

The country’s economic situation remains fraught. The national debt has ballooned to 95% of the size of its GDP in 2024. Meanwhile there are widespread fuel shortages; a decline in international currency reserves, meaning a likely further devaluation of the national currency; and a rising annual inflation rate that in July reached 24%.

Presidential candidates across the political spectrum promised economic austerity measures, like ending popular fuel subsidies.

This rightward shift also reflects growing divides among Bolivia’s political left, centered around Morales, a former labor leader and the first Indigenous president in a country where about half of the population is of native, non-European descent.

Morales’ 2006 victory was hailed at the time as a victory for Bolivian democracy. His government dramatically reduced the poverty rate, and expanded Bolivia’s middle class. However, critics contended that Morales also degraded democracy by, for example, stacking the courts and ignoring term limits. Morales’ time in office ended with allegations of fraud during the 2019 election, which he steadfastly denied. He fled the country soon after, returning in 2020 when his then-political ally and one-time protege Luis Arce assumed the presidency.

After seeing his popularity plummet during his term, Arce opted not to run this time around. Meanwhile, the coutry’s constitutional court, citing term limits, barred Morales from running for a fourth term as president. However, he continues to be a force in Bolivian politics. Recently, infighting between Morales, Arce and left-wing presidential candidates contributed to the inability to pass legislation meant to fix the current economic crisis.

These intraparty fights split the Bolivian left, leaving Morales supporters without a viable candidate.

Shut out, Morales campaigns for a null vote

In late July, the former president began actively campaigning for the invalid vote.

Campaigns promoting the blank or spoiled vote in presidential elections are not uncommon, with similar movements occurring in more than 30% of Latin American presidential elections during the 2010s. Indeed, nearly every country in the region has experienced at least one invalid vote campaign during a presidential election since 1980.

And as I found in the course of my research, most null vote campaigns self-consciously promote democratic values. Campaigners protest the persistent underperformance of democratic politics, ongoing corruption by high-ranking politicians or blatant efforts to rig elections.

Bolivia’s 2025 invalid vote campaign in some ways echoes those previous efforts. In Morales’ telling, Bolivia’s term limits curtailed his fundamental right to run for office and his supporters’ right to select their preferred candidate. Widespread ballot spoiling would be a way to send a strong message to those currently in power to allow Morales to run.

AP Photo/Jorge Saenz

But Morales’ campaign also faced challenges that often undo invalid vote campaigns. Such campaigns are generally unpopular with the public, and are even less popular when they are led by politicians who would benefit personally from an increase in the invalid vote. Morales was just such a candidate. Increased invalid vote rates would show his ability to sway the public and increase his political influence, something he appeared to acknowledge when declaring at a recent rally that he would have “won the elections” if the null vote reached 25%.

In this way, Morales is different from most null vote campaigners. He has been the central figure in Bolivian politics for nearly 20 years. He has a track record of both strong economic performance and of undermining Bolivian democracy and the rule of law. It is a testament to his popularity and influence that nearly 1 in 5 Bolivians spoiled their ballots.

The health of Bolivian democracy

Still, it would be a mistake to conclude that the increase in spoiled ballots signals overwhelming support for Morales, as he contends. Pre-election polling showed that Bolivians intended to cast invalid votes at a higher rate well before Morales began his campaign. Rather, Morales’s campaign likely harnessed existing anti-candidate sentiment, while leaching support from left-wing alternatives.

Additionally, while the spoiled vote rate was quite high, Morales did not achieve his goals: The null vote did not “beat” the runoff candidates, nor did it reach 25% of the vote. While Morales has staked a strong claim that the Bolivian public “voted but did not choose,” this argument is belied by the results: Most Bolivians did select a candidate, and a majority of them voted for a candidate from the political right. By that metric, Morales does not retain majoritarian support in Bolivia.

But neither should the relatively high number of invalid ballots be ignored. Over 1 million Bolivians used their ballots to send a message to politicians. Those leaders now have an opportunity to respond by working to restore trust with these voters.

Whoever wins the runoff in October 2025, Bolivian society will likely continue to be plagued by the social, political and economic divisions that have been present for years.

Indeed, the high rate of spoiled votes suggests that citizens are dissatisfied with their democratic choices. And those charged with protecting Bolivia’s democracy might well be advised to heed this signal.

![]()

Mollie J. Cohen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. 1 in 5 Bolivians spoiled their ballots – a sign of voter dissatisfaction as nation tips to the right – https://theconversation.com/1-in-5-bolivians-spoiled-their-ballots-a-sign-of-voter-dissatisfaction-as-nation-tips-to-the-right-263166