Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Lauren Eckert, Postdoctoral research fellow, Centre for Indigenous Fisheries, University of British Columbia

In the waters of the Salish Sea, endangered southern resident killer whales and the struggling Chinook salmon they depend on are at the centre of one of Canada’s most visible conservation conflicts.

Since 2019, Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has implemented area-based restrictions on Chinook fishing and other protective measures to safeguard the killer whales and their primary food source. These measures include area-based recreational fishing closures, interim sanctuary zones and voluntary seasonal vessel slowdown areas.

These prescriptions have stoked tensions, particularly between two groups often cast as distinct and opposed: recreational fishers and conservationists. The issue has spilled beyond local waters, surfacing on national media and even influencing fishery debates in Alaska.

Conflicts like this one aren’t unique. They surround — and can influence — many modern environmental, social and policy decisions. At their best, conflicts can bring attention to unmet community needs, spark dialogue and repair fractured relationships. But misunderstood or mishandled, they can harden divisions that stymie evidence-based decision-making, deepening distrust.

Too often in North America, default management approaches inflame such conflict rather than resolve it. But new collaborative research colleagues and I have conducted suggests pathways to transform conflict surrounding killer whale protection and Chinook fishing — and may offer broader insight for effectively managing conflicts around conservation efforts.

Our research

We surveyed more than 700 British Columbians, many of whom self-identified as either recreational fishers or conservationists. What we learned from participants has challenged dominant conflict narratives: nearly one-third of those who identified primarily as conservationists also identified as anglers, and almost half of anglers also identified as conservationists.

In other words, many of the people involved in this conflict occupy both sides of public debates, and bear multifaceted identities as they relate to whales, salmon and policy.

Yet public and political discourse about environmental management often reduces conflict to binary opposing opinions: do we support temporary recreational fishing restrictions to protect killer whales, or do we oppose them?

Humans — and conflicts — are not that simple, and treating them as such may be destructive to people, communities, policies and marine ecosystems.

Decades of research show, for instance, that conflicts are shaped not just by opinions, but by deeply rooted psychological characteristics, including identities, beliefs and values. These aspects of conflict are not trivial; they are central to how people make sense of their world, their relationships, and themselves.

We used surveys to measure beliefs, opinions and identity affiliations to assess not only opinions on killer whales and salmon management, but also the identities and beliefs beneath them.

What we found

We found that both anglers and those supporting conservation strongly tied their sense of self and well-being to the environment, as well as to their chosen identity groups (recreational fishers or conservationists). Despite disagreements, both groups valued salmon and whales — and both expressed frustration with DFO’s current management approaches.

We also identified the deeper roots of conflict between participants. Recreational fishers and conservationists differed in what they believed the fundamental priority of environmental management should be.

Conservationist respondents were more likely to emphasize protecting species regardless of their utility to humans, while recreational fishers expressed mixed views. Some agreed with that stance but others felt environmental management should prioritize species that benefit people directly or strike a balance between conservation and use.

One of our most striking findings came from comparing survey responses with social media commentary. When people responded to our survey, they tended to share their views with minimal inflammatory language. In contrast, data we extracted from Facebook discussions about the same issues contained far more hostile sentiments. Online, we saw more frequent expressions of anger, distrust, victimization and even violent rhetoric.

This isn’t surprising. Substantial research has identified that social media can amplify emotional responses, reward polarization and reduce the social cost of hostility. This finding indicates a potential negative feedback loop: when media and online discourse reduce complex conflicts to binary arguments, they risk entrenching people in “us versus them” stances.

Transforming conflict

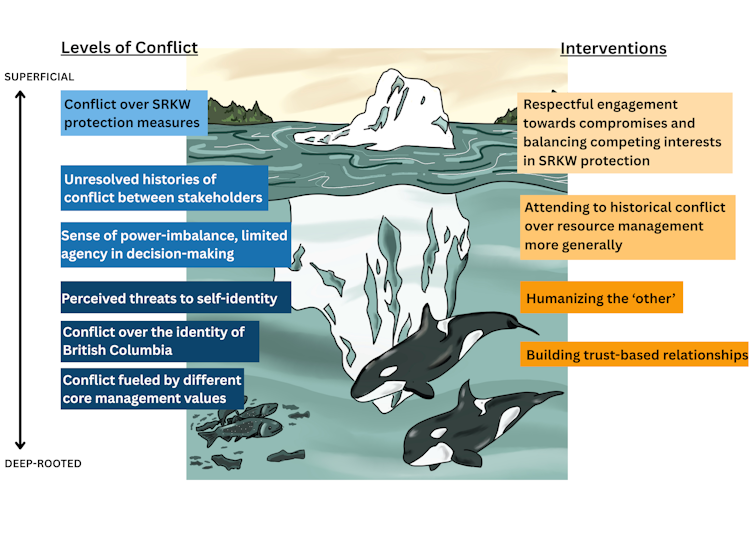

Given these insights, we propose a fundamental reorientation of how DFO and other managers approach such conflict. Rather than treating conflicts as problems to be managed through superficial consultations or short-term negotiations, decision-makers must address their roots.

This means adopting transformative approaches to addressing conflict: acknowledging deeper social roots of conflict, investing in long-term dialogue and relationship-building and creating space for mutual understanding even without consensus. Research shows it is much easier to find solutions when stakeholders feel seen, included and mutually-respected.

These solutions require time, resources, trained mediators and a commitment to engage with emotional and identity-based dimensions of conflict. They also offer something that current approaches have not: the possibility of durable, locally supported solutions, improved trust and collaboration.

(Author provided)

Conflict transformation approaches have proven effective in ameliorating entrenched conflicts between stakeholders over cougar management in the United States, elephant management in Mozambique and elsewhere.

As climate change, habitat degradation and species decline intensify, so will conflicts over environmental decisions. These conflicts may appear to be about salmon, whales or other species, but many of them are ultimately about people: their livelihoods, values, relationships, identities and visions for the future.

Accordingly, we need to stop treating conflict as an inconvenience to be managed or avoided. Instead, policymakers can leverage complex, entrenched conflicts as opportunities to identify the deeper roots of what’s at stake and create dialogue and decision-making frameworks that acknowledge people’s lived realities while building the trust needed for coexistence.

![]()

Lauren Eckert has previously been affiliated with Raincoast Conservation Foundation. This research was supported by a Canada Vanier Graduate Scholarship and a Raincoast Conservation Fellowship.

– ref. In the Salish Sea, tensions surrounding killer whales and salmon are about more than just fishing – https://theconversation.com/in-the-salish-sea-tensions-surrounding-killer-whales-and-salmon-are-about-more-than-just-fishing-263524