Source: The Conversation – UK – By Jean-Baptiste Burnet, Lead R&T Scientist, Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST)

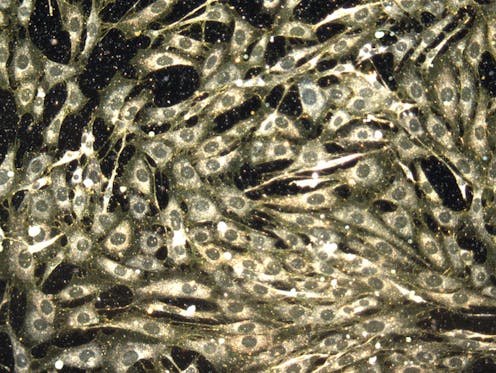

Microbes in water are like invisible travellers – and some carry disease with them. Keeping the water that flows through our treatment plants, rivers and taps healthy and safe from microbial infection is a challenge.

The distribution of microbes varies considerably across time and space. This makes them difficult to track through conventional monitoring programmes which rely on infrequent sampling (monthly or weekly at best) at fixed locations.

When contamination occurs, it can be very episodic (for just a few hours, say) and microbial concentrations can be extremely low. Without advanced and highly sensitive detection methods, some microbes will remain undetected.

Continuous monitoring is the best way to detect epidemics before they explode, identify contaminations before they spread, and proactively protect public health. In the small country of Luxembourg, we have been trialling new online monitoring initiatives such as Microbs and Cyanowatch to achieve this at a national level.

Luxembourg acts as a “living laboratory” where, by collaborating directly with local authorities, our team at the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (List) is developing ways to prevent swimmers’ exposure to toxic bacteria, for example, or to protect people during viral outbreaks like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Water flows from natural sources through streams and rivers to treatment plants, then through distribution networks to our homes, and finally to wastewater treatment – before returning back into the environment. At each step, our dedicated observatories, equipped with multiple sampling and measurement instruments, continuously collect samples and monitor microbial water quality.

These observatories mean we can assess risks to the Luxembourg public’s health continuously – and take rapid, meaningful decisions early when needed.

Meet the microbes

These advanced surveillance systems become even more crucial as global changes intensify the microbial threats we face. Climate change, population growth, biodiversity loss and agricultural intensification are creating an explosive cocktail for the emergence – or re-emergence – of human and animal pathogens, by enabling more contact between people and animals.

Bilanol/Shutterstock

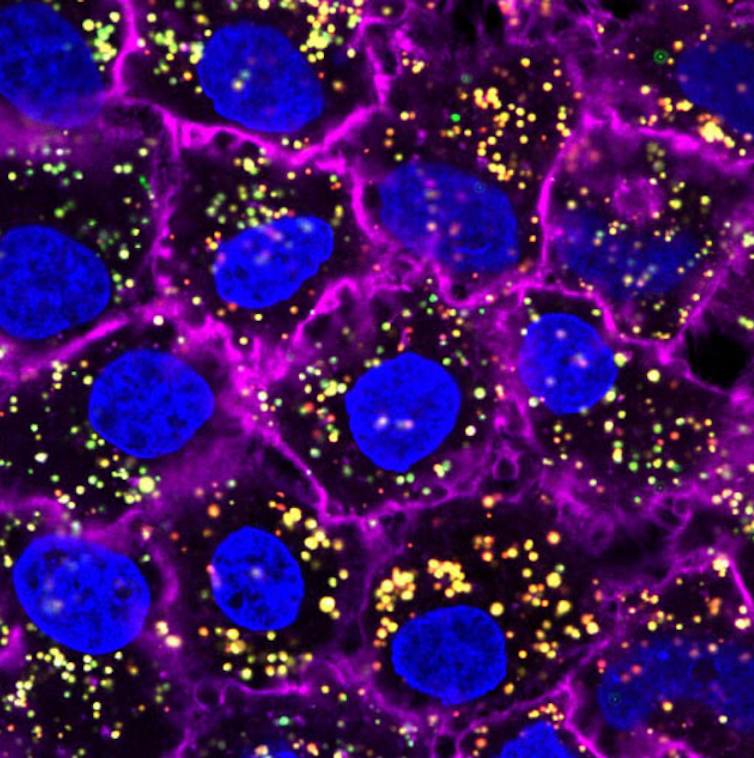

Blue-green algae known as cyanobacteria are ancient bacteria that can turn toxic when flooded with excess nutrients (phosphorous and nitrogen) from sewage and agricultural run-off. In warm, stagnant waters, this can create massive algal blooms that cost societies billions each year.

These blooms can disrupt natural ecosystems through the release of toxins into the water. In acute cases of human exposure, they can trigger gastro-intestinal, skin or neurological symptoms.

Viruses present a different challenge. These tiny invaders survive in water for extended periods, spreading rapidly through interconnected wastewater and drinking water supplies. From SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) to the noroviruses that cause vomiting and diarrhoea, they can trigger major outbreaks of disease.

This triple threat – climate change-induced water temperature increase, nutrient pollution, and the complex ways that pathogens circulate – demands monitoring approaches that can detect these hazards before they strike.

Monitoring these microbes

At List, we are creating innovative tools to protect public health by closely monitoring microbial hazards.

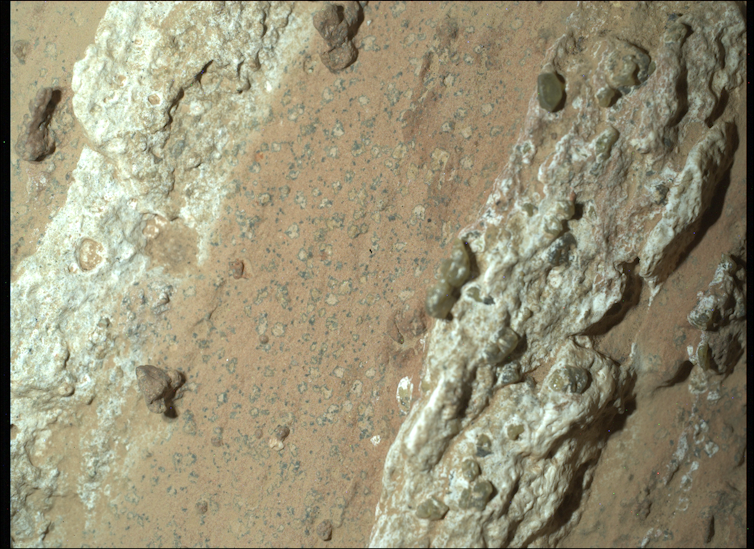

For example, at Haute-Sûre reservoir (the country’s main recreation site and drinking water supplier), a field observatory is equipped with automated instruments for real-time, 24-7 monitoring of cyanobacteria blooms. Automated cameras take hourly images at key locations, and sensor buoys in the water detect early signs of harmful blooms.

When a risk is detected, on-site toxin tests are performed – with results available within an hour. Local authorities can be alerted immediately to issue bathing bans in contaminated areas while keeping safe zones open. Such bans can also be lifted more quickly using this system.

Another water observatory was recently set up in Luxembourg to remotely and continuously monitor bacteria in drinking water. Using sensors which transmit high-resolution data in near-real time, this observatory tracks changes in microbial water quality at strategic spots across the drinking water supply network. This helps improving water management and supports the long-term supply of safe drinking water.

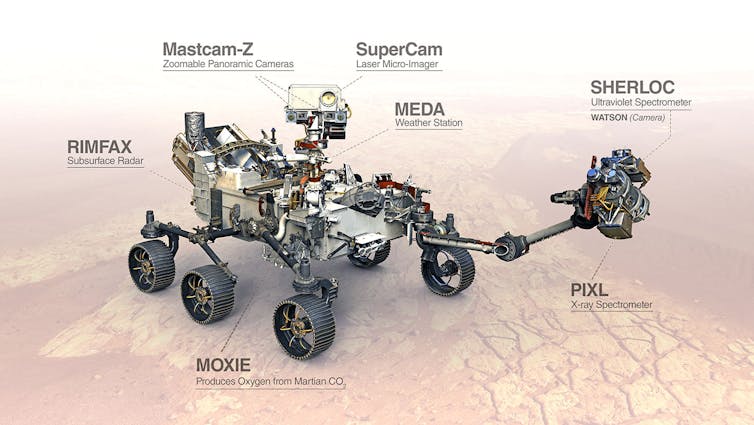

Meanwhile, our wastewater-based observatory, Microbs, brings together information from the inlets of 13 wastewater treatment plants across the country to monitor viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. On-site instruments autonomously collect wastewater samples which are analysed in the lab to provide an early warning of viral outbreaks – often before they appear in the community.

Covering around 75% of Luxembourg’s population, this observatory played a key role during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data, shared regularly with health authorities, became as important as case numbers or hospitalisations, helping to guide targeted testing and implement an early response to protect the population.

To complement our technology-driven observatories, we have also launched a citizen-based observatory. Together with UK scientists, we adapted an app called Bloomin’ Algae which allows the public to report and upload photos of cyanobacteria blooms at Luxembourg’s bathing sites. These can then be verified by experts, with confirmed sightings appearing on a public map.

As climate change and population growth put strain on precious water resources, technology and citizen input, used together, are an important way to improve water monitoring and protect public health, quickly.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Jean-Baptiste Burnet receives funding from the National Research Fund Luxembourg (project 329963 INTER AUDACE) and from the Ministry of Environment (SMARTWATER, CYANOMON and CYANOWATCH projects).

Leslie Ogorzaly receives funding from the National Research Fund Luxembourg (Grant numbers: COVID-19/2022/14806023/CORONASTEP+, C21/BM/15793340/VIRALERT) and jointly from the Ministry of Health and Social Security and the Ministry of Environment (SUPERVIR project).

– ref. How Luxembourg detects microbes in its water supply before they pose a health risk – https://theconversation.com/how-luxembourg-detects-microbes-in-its-water-supply-before-they-pose-a-health-risk-258018