Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Jo Mackiewicz, Professor of Rhetoric and Professional Communication, Iowa State University

A few years ago, while working as a professor and as a welder at a small repair and fabrication shop, I went looking for books about women in the skilled trades. In the few I found, one stood out in how it made way for tradeswomen’s voices: political scientist Jean Reith Schroedel’s 1985 classic “Alone in a Crowd: Women in the Trades Tell Their Stories.”

Her first book after earning her Ph.D., “Alone in a Crowd” drew on Schroedel’s own experience working blue-collar jobs. She interviewed 25 women – machinists, truck drivers, electricians and more – whose stories revealed the exhaustion, danger, harassment and pride that shaped their working lives.

In her introduction, Schroedel noted that American women’s work opportunities have expanded and contracted in step with their rights as citizens. During World War II, for example, women entered the industrial trades in large numbers, only to be forced out when the war ended. They began to find their way back to such work after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which barred discrimination based on sex.

The women who entered skilled trades after 1964 made up just a small share of the workforce, and they faced a wide range of challenges, including sexual harassment. Schroedel’s interviewees talked at length about being harassed and threatened by co-workers and being retaliated against for reporting sexism, racism and bullying.

So what, if anything, has changed, and what’s stayed the same?

Women hold just 5% of jobs in the trades

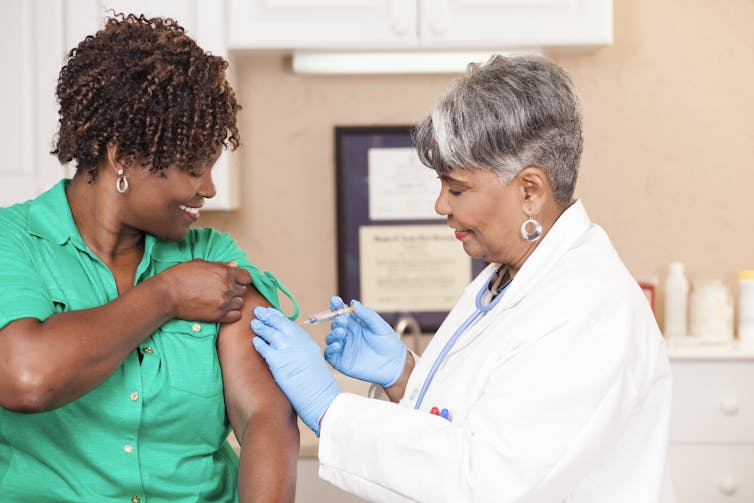

For one thing, it’s still rare for women to work in the skilled trades. Around 95% of the trades workforce is male, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Discrimination remains a barrier to entry: A 2020 research review published by sociologist Donna Bridges and her colleagues found that sexual harassment, stereotyping, ostracization and surveillance kept women from entering and staying in construction trades.

According to a 2023 analysis of 25 studies by Kimberly Riddle and Karen Heaton, sexual harassment of tradeswomen becomes more likely when male workers view women as outsiders, when women have less seniority and when jobs are physically demanding. These issues were common in 1985, and they remain so today.

Jo Mackiewicz

In addition to these meta-analyses – or studies of studies – new research has revealed other similarities between 1985 and now. In a study published in 2022, sociologist Elizabeth Wulff and her colleagues interviewed 15 tradeswomen and found that types of social and cultural capital, such as growing up in a family of tradespeople and being physically strong, led them to be more successful.

Meraiah Foley, a researcher who studies workplace gender equity, and her co-researchers focused on how tradeswomen experience gender harassment – harassment not sexual in nature but focused on gender characteristics. Studying women in aviation and automotive repair in 2019, they found women experience “jokes, jibes, and belittling comments” and bosses who allow such behavior. These behaviors reinforce the view that women are outsiders, making it harder for them to succeed.

Steps forward: Respect, research and cultural shifts

So, has anything improved for women in trades since 1985? While the research clearly shows that problems such as stereotyping, disrespect, scrutiny and harassment haven’t gone away, it would be wrong to say that nothing’s changed.

In Chapter 10 of my 2025 book “Learning Skilled Trades in the Workplace,” I discuss some of the challenges that I’ve encountered as a woman in a welding shop. But I also highlight the ways that my boss and my co-workers have respected my ideas and input, have encouraged me when I’ve made mistakes, have praised my successes, and have generously shared their knowledge.

It’s possible to see change in apprenticeship programs aimed at girls and women, scholarships for women studying trades, professional organizations to support tradeswomen, and, perhaps most important, growing numbers of women in apprenticeships and skilled-trades work. While the problems that tradeswomen encounter in 2025 haven’t changed in nature since 1985, it seems these problems are more readily acknowledged and less ubiquitous.

Also, the body of research on tradeswomen is growing, which can lead to new solutions to old problems. In 2021, for example, Bridges and her co-researchers looked to scholarship on resilience to understand how male-dominated industries might better support tradeswomen. They found that mentoring, role models and networking opportunities, as well as formal health and safety rules and policies such as flexible schedules, help tradeswomen thrive.

Similarly, while most research on women in skilled trades has historically focused on tradeswomen in the U.S., Australia, New Zealand and other Western countries, new scholarship is providing insight into the experiences of tradeswomen elsewhere.

For example, education researchers Joyceline Alla-Mensah and Simon McGrath published an article in March 2025 about barriers to Ghanaian women’s participation in skilled trades. Their interviews brought to light new findings – for example, the importance of land ownership to Ghanaian tradeswomen. Researchers are just now beginning to understand the experiences of women in trades all around the world.

Back in 1985, Schroedel wrote that she had three goals for “Alone in a Crowd”: to let women doing nontraditional work know that they’re not alone, to shed light on their work situations, and to tell the largely overlooked stories of working-class women.

While the outlook for tradeswomen is brighter than it was back in 1985, it would nevertheless be possible to begin a 2025 sequel to “Alone in a Crowd” with the same three goals. And that says something about how far the U.S. has yet to go.

![]()

I work for Howe’s Welding and Metal Fabrication.

– ref. 4 decades after the landmark book ‘Alone in a Crowd,’ women in the trades still battle bias – a professor-turned-welder reflects – https://theconversation.com/4-decades-after-the-landmark-book-alone-in-a-crowd-women-in-the-trades-still-battle-bias-a-professor-turned-welder-reflects-262307