Source: The Conversation – UK – By Dafydd Townley, Teaching Fellow in US politics and international security, University of Portsmouth

Following the shooting of his political ally, the far-right activist and commentator Charlie Kirk, on September 10, Donald Trump has signalled his intention to pursue his political enemies – what he refers to as the “radical left”. In the days following Kirk’s assassination, the US president took to social media to announce he was planning on designating the antifa movement a terrorist organisation.

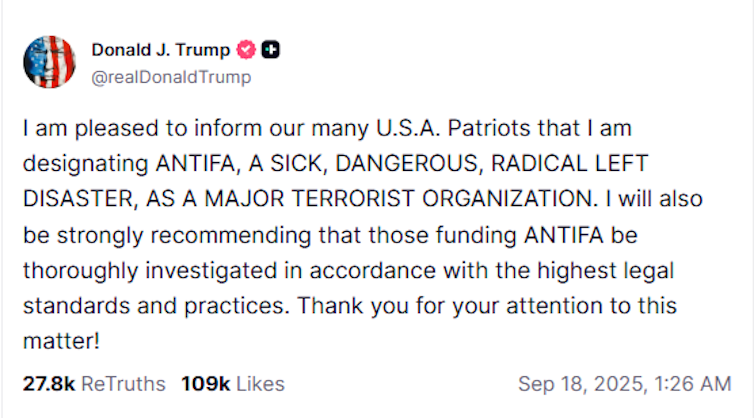

TruthSocial

Calling antifa a “SICK, DANGEROUS, RADICAL LEFT DISASTER”, Trump also threatened to investigate any organisations funding antifa. And when Kirk’s widow, Erika, said she forgave the person who has been arrested for the murder, Trump said he did not. “I hate my opponent,” he told people at a memorial event for Kirk at the weekend.

But Trump’s decision to target his ideological opponents faces significant legal and constitutional issues.

It’s not the first time that Trump has threatened such action. In 2020, he threatened the same thing on social media in response to the widespread protests following the death of George Floyd. But just as is the case in the present day, there was no legal process to designate any domestic group as a terrorist organisation.

Trump also appears to have misunderstood what antifa is. He represents it as a defined organisation, when it is more like a broad ideology. Mark Bray, a historian at Rutgers University, New Jersey, described the movement as similar to feminism. “There are feminist groups, but feminism itself is not a group. There are antifa groups, but antifa itself is not a group,” he said.

Antifa is shorthand for “anti-fascist”. It has no centralised leadership or defined structure. Despite being able to mobilise to oppose far-right groups with protests and counter-demonstrations, the movement’s dispersed character hampers efforts to classify it as an organisation of any formal kind.

Plans to use Rico laws

One of the laws Trump has suggested that US attorney-general Pam Bondi could use against antifa is the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (Rico) Act of 1970. This was passed by Richard Nixon to tackle organised crime, but its application has since been extended to investigate various other organisations and individuals. This has included Donald Trump himself, over alleged irregularities in Georgia during the 2020 presidential election.

Although it would be challenging, the Trump administration might try to use Rico laws to break up antifa’s network if the movement is classified as a terrorist organisation. Authorities could argue that specific individuals are engaged in a series of racketeering activities, including any acts of violence or other criminal behaviour linked to the movement. But this method would undoubtedly face considerable legal challenges.

If the US government finds a way to define antifa as a group and identify people as members – it’s not clear at the moment whether this might be possible – it would then be possible to seek out and attempt to prosecute anyone who facilitates their activities or gives them funds. But as David Schanzer, director of the Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security at Duke University, North Carolina, told the BBC this week: “Under the First Amendment, no one can be punished for joining a group or giving money to a group.”

Nevertheless, antifa activists may be subject to increased surveillance if the movement is proscribed. Such actions would mirror the FBI’s extra-legal counterintelligence programme (Cointelpro) that targeted the new left in America during the 1960s. Civil rights groups and Democrats would inevitably raise serious questions concerning executive overreach and possible violations of civil liberties.

Power grab

Labelling antifa as a terrorist group would allow the federal government to circumvent state-controlled law enforcement. It may seek to do so especially in Democrat states and cities where authorities might be hesitant to act against liberal or left-wing demonstrators. Federal agencies such as the FBI and Department of Homeland Security might be drafted in to lead investigations and prosecutions, superseding state authorities.

This consolidation of power would create further legal and political difficulties. While the Posse Comitatus Act is supposed to bar the use of federal military personnel for domestic law enforcement, there are exceptions. If the president invokes the Insurrection Act of 1807 it would give him the power to deploy troops to restore order.

Antifa’s classification as a terrorist organisation could have profound effects on the first amendment rights of large numbers of law-abiding US citizens. It would be a serious danger to American democracy if US citizens were unable to voice their protest and exercise their right to free speech because of this classification.

A decision to vilify anti-establishment rhetoric would set a dangerous precedent for silencing dissent and infringing fundamental constitutional rights in the US during the 21st century.

The administration’s position on domestic extremism has changed significantly with Trump’s plan to label antifa as a terrorist organisation. The political consequences are far-reaching, potentially setting important precedents for the balance between civil liberties and US national security. This could shift the focus more toward security and potentially harm individual freedoms.

But it’s unlikely that the Trump administration will be deterred by any constitutional considerations. This is an executive branch that has acted first and sought justification through the courts. There will be a lengthy legal process if Trump follows through on this. But by the time courts make their final decision, the damage will already have been done to the US political system.

![]()

Dafydd Townley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Going after ‘antifa’: Donald Trump’s plans to crush his political foes – https://theconversation.com/going-after-antifa-donald-trumps-plans-to-crush-his-political-foes-265686