Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Lucy Xiaolu Wang, Assistant Professor, Department of Resource Economics, UMass Amherst

Pharmaceutical innovation saves lives. But not every “new” drug is truly new.

Patents are designed to reward breakthrough inventions by granting the inventors temporary monopoly rights to recoup the costs of research and development and to encourage future innovation. But firms may also exploit the system in ways that make drugs more expensive and less accessible to patients. A 2023 study found that 78% of drugs associated with new patents weren’t actually new drugs but minor modifications.

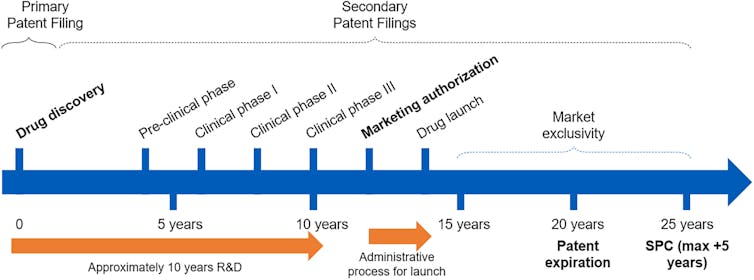

After obtaining a drug’s primary patent, pharmaceutical companies often file additional ones to extend their monopoly rights. This practice – called evergreening – may cover new dosages, delivery methods, drug combinations and conditions. Though some of these secondary patents improve the effectiveness or convenience of treatment, many have little effect on health outcomes. More often, these subsequent changes are mainly used to strategically prolong market exclusivity, delay competition from generics and keep drug prices high.

Such practices raise concerns about drug access and affordability, especially when companies use minor tweaks to block cheaper alternatives, with little benefit to patients. Yet distinguishing between truly innovative improvements and low-value extensions has been challenging for regulators and courts.

I am an economist studying innovation and digitization in health care markets. My colleague Dennis Byrski and I have focused on how regulatory transparency plays a role in curbing weak patents. Our recently published research found that when clinical trial data become public, this disclosure makes it harder for firms to obtain patents for incremental changes that add little therapeutic benefit for patients.

What makes a drug patentable?

According to World Intellectual Property Organization, a patentable invention needs to be novel and non-obvious.

Novelty means the invention hasn’t been previously documented in publicly available information – such as patents, publications or products – in fields related to an invention before the filing date. This information is often referred to as prior art.

Non-obviousness means the invention wouldn’t be obvious – an easy tweak or routine step in the process – to a skilled person in the field based on existing knowledge. For example, if prior art reveals that a new combination therapy improves treatment outcomes, officials may deem subsequent patents using the same drug cocktail as obvious and refuse to grant or enforce the patent.

For drugs, these two concepts are deeply intertwined with safety and efficacy. If a company reformulates a drug – say, by changing an inactive ingredient or tweaking the dose – it is not always easy to determine whether such changes improve patient health without further testing in the clinic.

According to guidelines from the European Patent Office, clinical trial results can be critical to prior art, particularly when revealing unexpected or previously undisclosed therapeutic benefits. Patent advisers have also noted that evidence from trials can play a decisive role in assessing novelty and non-obviousness.

However, comprehensive clinical trial results are often either unavailable or not disclosed until the start of the marketing authorization process, when a company submits a comprehensive application to regulators to formally approve a drug for sale.

In fact, while European drug regulators strongly encourage companies to disclose clinical trial data early in the process, firms can defer the release of study data for up to seven years after trial completion or until the drug goes on the market – whichever occurs first. The latter is more binding for firms wishing to delay the release of critical data points to avoid competition.

Marketing authorization changes the game

Given the lengthy drug development process, most firms file the primary patent of a drug early on, often before starting clinical trials and obtaining data on treatment safety and efficacy.

This information is required when applying for marketing authorization and is usually disclosed through detailed Phase 3 clinical trial results. That data can then become prior art to evaluate subsequent patent applications, making it harder to obtain low-value patents. But does marketing authorization actually affect whether drug companies pursue follow-on patents?

Dennis Byrski and Lucy Xiaolu Wang, CC BY-NC-ND

To investigate how patenting behaviors change after marketing authorization, we specifically used data from the German Patent and Trade Mark Office and the European Patent Office’s Worldwide Patent Statistical Database. Legal and innovation scholars worldwide often view the European agency as the gold standard for patent quality, and scholars use European drug patents as high-quality benchmarks when evaluating U.S. drug patents.

Furthermore, the U.S. has seen four major Supreme Court cases involving patent eligibility between 2010 and 2014, including two focused on the pharmaceutical sector. The European setting allowed us to study changes in patenting behavior in the absence of direct legal changes to the patent system.

Identifying primary patents isn’t easy. Because they often aren’t labeled in drug patent databases, researchers often need to manually review lengthy patent texts for U.S. drugs. We overcome this difficulty by tracking supplementary protection certificates granted by the European patent term extension system. This system requires companies to specify which main drug patent to extend after marketing authorization and before patent expiration.

We found that disclosing prior art – such as existing knowledge from clinical trial data – during marketing authorization makes it harder to obtain low-value, follow-on patents afterward. This was reflected by a sharp drop in self-citations from subsequent patents for that drug and other patents with similar disease targets.

In contrast, subsequent self-citations from substantive product patents – such as those for new drug derivatives – and patents targeting different disease areas continue at roughly the same pace as before marketing authorization.

These findings suggest that transparency in the authorization process effectively deters companies from obtaining low-value patent extensions without discouraging further research and development.

Importantly, we saw similar patenting adjustments among the patent owner’s competitors, collaborators and generic manufacturers. This pattern suggests that changes in patenting behaviors may not be driven by reduced profit-seeking after drug approval, as other firms would have a higher motivation to obtain related weak patents after seeing a drug’s market potential. Once clinical trial data is public, this seems to have a systemwide effect on reducing low-value, follow-on patents, likely driven by a higher bar for novelty.

Interestingly, we didn’t see similar declines in patent filings after earlier milestones in the drug development process, such as the end of Phase 2 clinical trials. These milestones provide information on drug quality but involve less data disclosure, so they’re less likely to provide usable prior art for patent examiners.

In other words, it’s the full clinical transparency at marketing authorization that makes a big difference.

What this means for patients and policymakers

Drug patent quality matters. Weak patents can drive up drug costs and delay access by blocking competition from generics long after the market has rewarded a company for its main innovation. The results can be costly for patients, insurers and public health systems, and it risks steering R&D toward marginal tweaks instead of breakthrough therapies.

Our findings suggest that integrating regulatory information, including clinical trial data, into patent assessments can indirectly improve patent quality. Doing so can reduce the number of weak drug patents filed more for strategic considerations rather than improving patient health.

Better aligning patents with genuine innovation is not just a legal concern but a public health imperative. Transparency, paired with smarter review systems, can help raise the bar for drug development and reward the kinds of innovations that truly improve health.

![]()

Lucy Xiaolu Wang does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Some new drugs aren’t actually ‘new’ – pharmaceutical companies exploit patents and raise prices for patients, but data transparency can help protect innovation – https://theconversation.com/some-new-drugs-arent-actually-new-pharmaceutical-companies-exploit-patents-and-raise-prices-for-patients-but-data-transparency-can-help-protect-innovation-258989