Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Robyn Arianrhod, Affiliate, School of Mathematics, Monash University

The Irish mathematician and physicist William Rowan Hamilton, who was born 220 years ago last month, is famous for carving some mathematical graffiti into Dublin’s Broome Bridge in 1843.

But in his lifetime, Hamilton’s reputation rested on work done in the 1820s and early 1830s, when he was still in his twenties. He developed new mathematical tools for studying light rays (or “geometric optics”) and the motion of objects (“mechanics”).

Intriguingly, Hamilton developed his mechanics using an analogy between the path of a light ray and that of a material particle. This is not so surprising if light is a material particle, as Isaac Newton had believed, but what if it were a wave? What would it mean for the equations of waves and particles to be analogous in some way?

The answer would come a century later, when the pioneers of quantum mechanics realised Hamilton’s approach offered more than just an analogy: it was a glimpse of the true nature of the physical world.

The puzzle of light

To understand Hamilton’s place in this story, we need to go back a little further. For ordinary objects or particles, the basic laws (or equations) of motion had been published by Newton in 1687. Over the next 150 years, researchers such as Leonard Euler, Joseph-Louis Lagrange and then Hamilton made more flexible and sophisticated versions of Newton’s ideas.

“Hamiltonian mechanics” proved so useful that it wasn’t until 1925 – almost 100 years later – that anybody stopped to revisit how Hamilton had derived it.

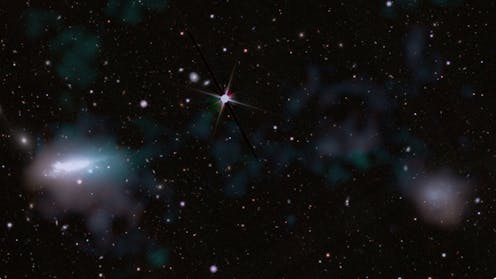

His analogy with light paths worked regardless of light’s true nature, but at the time, there was good evidence that light was a wave. In 1801, British scientist Thomas Young had performed his famous double-slit experiment, in which two light beams produced an “interference” pattern like the overlapping ripples on a pond when two stones are dropped in. Six decades later, James Clerk Maxwell realised light behaved like a rippling wave in the electromagnetic field.

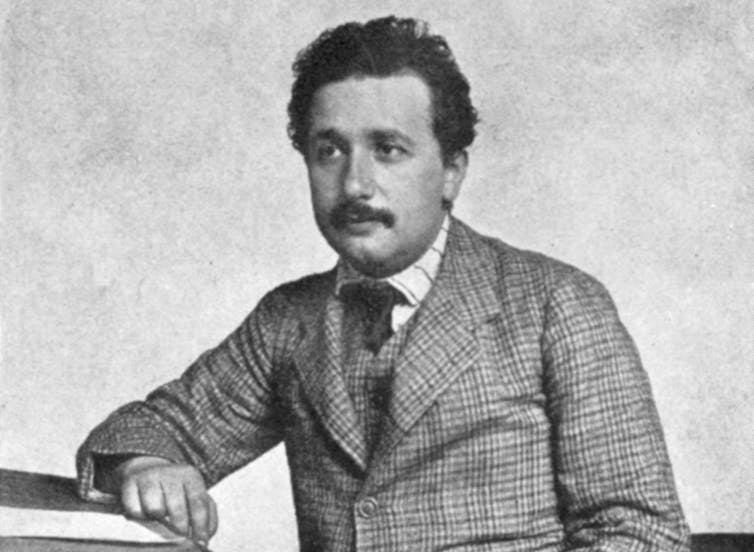

But then, in 1905, Albert Einstein showed some of light’s properties could only be explained if light could also behave as a stream of particle-like “photons” (as they were later dubbed). He linked this idea to a suggestion made by Max Planck in 1900, that atoms could only emit or absorb energy in discrete lumps.

Energy, frequency and mass

In his 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect, where light dislodges electrons from certain metals, Einstein used Planck’s formula for these energy lumps (or quanta): E = hν. E is the amount of energy, ν (the Greek letter nu) is the photon’s frequency, and h is a number called Planck’s constant.

But in another paper the same year, Einstein introduced a different formula for the energy of a particle: a version of the now-famous E = mc ². E is again the energy, m is the mass of the particle, and c is the speed of light.

So here were two ways of calculating energy: one, associated with light, depended on the light’s frequency (a quantity connected with oscillations or waves); the other, associated with material particles, depended on mass.

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Did this suggest a deeper connection between matter and light?

This thread was picked up in 1924 by Louis de Broglie, who proposed that matter, like light, could behave as both a wave and a particle. Subsequent experiments would prove him right, but it was already clear that quantum particles, such as electrons and protons, played by very different rules from everyday objects.

A new kind of mechanics was needed: a “quantum mechanics”.

The wave equation

The year 1925 ushered in not one but two new theories. First was “matrix mechanics”, initiated by Werner Heisenberg and developed by Max Born, Paul Dirac and others.

A few months later, Erwin Schrödinger began work on “wave mechanics”. Which brings us back to Hamilton.

Schrödinger was struck by Hamilton’s analogy between optics and mechanics. With a leap of imagination and much careful thought, he was able to combine de Broglie’s ideas and Hamilton’s equations for a material particle, to produce a “wave equation” for the particle.

An ordinary wave equation shows how a “wave function” varies through time and space. For sound waves, for example, the wave equation shows the displacement of air, due to changes in pressure, in different places over time.

But with Schrödinger’s wave function, it was not clear exactly what was waving. Indeed, whether it represents a physical wave or merely a mathematical convenience is still controversial.

Waves and particles

Nonetheless, the wave-particle duality is at the heart of quantum mechanics, which underpins so much of our modern technology – from computer chips to lasers and fibre-optic communication, from solar cells to MRI scanners, electron microscopes, the atomic clocks used in GPS, and much more.

Indeed, whatever it is that is waving, Schrödinger’s equation can be used to predict accurately the chance of observing a particle – such as an electron in an atom – at a given time and place.

That’s another strange thing about the quantum world: it is probabilistic, so you can’t pin these ever-oscillating electrons down to a definite location in advance, the way the equations of “classical” physics do for everyday particles such as cricket balls and communications satellites.

Schrödinger’s wave equation enabled the first correct analysis of the hydrogen atom, which only has a single electron. In particular, it explained why an atom’s electrons can only occupy specific (quantised) energy levels.

It was eventually shown that Schrödinger’s quantum waves and Heisenberg’s quantum matrices were equivalent in almost all situations. Heisenberg, too, had used Hamiltonian mechanics as a guide.

Today, quantum equations are still often written in terms of their total energy – a quantity called the “Hamiltonian”, based on Hamilton’s expression for the energy of a mechanical system.

Hamilton had hoped the mechanics he developed by analogy with light rays would prove widely applicable. But he surely never imagined how prescient his analogy would be in our understanding of the quantum world.

![]()

Robyn Arianrhod does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. 100 years before quantum mechanics, one scientist glimpsed a link between light and matter – https://theconversation.com/100-years-before-quantum-mechanics-one-scientist-glimpsed-a-link-between-light-and-matter-261551