Source: The Conversation – USA – By James T. Stroud, Assistant Professor of Ecology and Evolution, Georgia Institute of Technology

We are lizard biologists, and to do our work we need to catch lizards – never an easy task with such fast, agile creatures.

Years ago, one of us was in the Bahamas chasing a typically uncooperative lizard across dense and narrow branches, frustrated that its nimble agility was thwarting efforts to catch it. Only when finally captured did we discover this wily brown anole was missing its entire left hind leg. This astonishing observation set our research down an unexpected path.

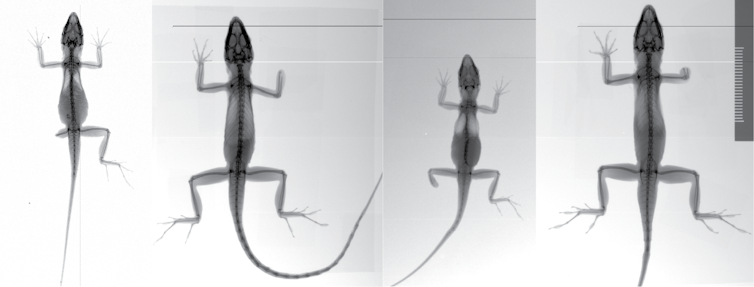

That chance encounter led us to collaborate with over 60 colleagues worldwide to document what we suspected might be a broader phenomenon. Our research uncovered 122 cases of limb loss across 58 lizard species and revealed that these “three-legged pirates” – the rare survivors of traumatic injuries – can run just as fast, maintain healthy body weight, reproduce successfully and live surprisingly long lives.

To be clear, most lizards probably do not survive such devastating injuries. What we’re documenting are the exceptional cases that defy our expectations about how natural selection works.

Christopher Anderson

This discovery is startling because lizard limbs represent one of biology’s most studied examples of evolutionary adaptation. For decades, scientists have demonstrated that even tiny differences in leg length between individual lizards can mean the difference between life and death – affecting their ability to escape predators, catch prey and find mates.

Since subtle variations matter so much, biologists have long assumed that losing an entire limb should be catastrophic.

Yet our global survey tells a different story about these remarkable survivors. Working with colleagues across six continents, we found limb-damaged lizards across nearly all major lizard families, from tiny geckos to massive iguanas.

These animals had clearly healed from whatever trauma caused their injuries – likely accidents or the failed attempts of a predator to eat them. Perhaps most remarkably, we documented surviving limb loss even in chameleons, tree-climbing specialists whose movements seem to require perfect limb coordination.

Thriving, not just surviving

The body condition of these lizards was most surprising. Rather than appearing malnourished, many limb-damaged lizards were actually heavier than expected for their size, suggesting they were successfully finding food despite their handicap. Some were actively reproducing, with females found carrying eggs and males observed successfully mating.

Jason Kolbe/Jonathan Losos

These findings force us to reconsider some basic assumptions about how evolution might work in wild populations. Charles Darwin envisioned natural selection as an omnipresent force, “daily and hourly scrutinizing” every feature.

But perhaps selection is more episodic than constant. Maybe sometimes limb length matters tremendously, while during other times – such as when food is abundant and predators are scarce – limb length matters less and three-legged lizards can flourish.

These lizard survivors showcase the incredible solutions that millions of years of evolution have built into their biology. Rather than being passive victims of their injuries, these lizards may survive by actively choosing safer habitats or hunting strategies, using smart behavior to avoid situations where their disability would be a disadvantage.

Biological engineering in action

Our research combines old-fashioned natural history observations with cutting-edge, biomechanical analysis.

We use high-speed cameras and computer software that can track movement frame by frame to analyze running mechanics invisible to the naked eye. This combination of field biology and laboratory precision allows us to understand not just that these lizards survive, but how they accomplish this remarkable feat.

When we tested the three-legged lizards’ athletic performance, the results defied expectations. Some animals were clearly impaired in their sprinting capabilities, but others actually ran faster than fully-limbed individuals of the same size across a 2-meter dash during our “Lizard Olympics.”

High-speed video analysis revealed their secret: The speedy survivors compensate through creative biomechanical solutions. One brown anole missing half its hind limb dramatically increased its body undulation during sprinting, using exaggerated snakelike movements to compensate for the missing leg.

By documenting the unexpected – the seemingly impossible survivors – we’re reminded that nature still holds surprises that can fundamentally change how we think about life itself.

![]()

Jonathan Losos receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

James T. Stroud does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. 3-legged lizards can thrive against all odds, challenging assumptions about how evolution works in the wild – https://theconversation.com/3-legged-lizards-can-thrive-against-all-odds-challenging-assumptions-about-how-evolution-works-in-the-wild-262467