Source: The Conversation – UK – By Frances Fowle, Personal Chair of Nineteenth-Century Art, History of Art, University of Edinburgh

The Van Gogh Museum’s new exhibition, Van Gogh and the Roulins – Together Again at Last, celebrates an important family reunion. It brings together 14 portraits of the wife and three children of the postman Joseph Roulin – Vincent van Gogh’s closest friend and supporter while he was based in the southern French town of Arles.

The exhibition is a work of art in itself: tightly focused, beautifully designed and accompanied by an excellent catalogue. Additional works and props (such as Roulin’s chair) contextualise the show, but it is the portraits of the Roulins – Joseph, Augustine, 17-year-old Armand, 11-year-old Camille and baby Marcelle – that take centre stage.

Hung in three rooms on contrasting deep blue and orange walls they demonstrate the new direction that Van Gogh’s work was taking during a crucial period of his artistic development.

As a group they represent, on one level, the artist’s personal longing for the stability of a wife and family and, on another, his radical rethinking of portraiture as a genre. They were painted at a time when, in correspondence with his two friends, Paul Gauguin and Emile Bernard, he was struggling with the idea of art as “abstraction”. That is, as a fusion of the real and the imaginary.

Van Gogh wanted to paint ordinary people as he “felt” them and to raise them to the level of the universal. He was interested in creating symbolic “types”, of portraiture such as “the poet” or “the soldier”, and also sought to evoke the character and soul of the sitter.

As the exhibition cleverly demonstrates – through the careful placement of comparative works and “glimpses” via various sight-lines – he was inspired by artists such as Rembrandt, Frans Hals and even Honoré Daumier, all of whom devoted themselves to what Van Gogh termed “the painting of humanity”.

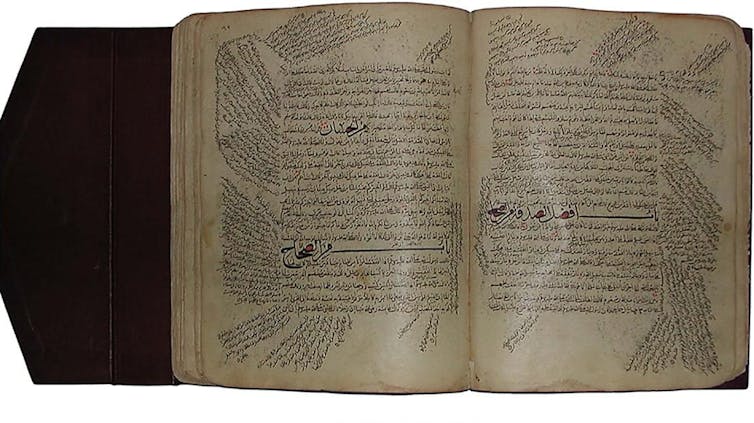

Museum of Fine Arts Boston/Rijksmuseum

In July and August 1888 Van Gogh painted two expressive and colourful portraits of the bearded Roulin, whom he viewed as the modern equivalent of Frans Hals’s painting, The Merry Drinker (1628-1630). The first portrait shows this jolly barfly in his smart blue cap and uniform leaning awkwardly on a table in the Café de la Gare.

It recalls the artist’s description of the postman in a letter to Bernard as “something of an alcoholic, and with a high colour as a result”. He was also a “raging republican” and the two spent long hours conversing about politics.

In October Van Gogh moved to the “little yellow house” in Arles, where he rented two rooms and a studio for only 21 francs 50 centimes a month. A reconstruction of the house is installed on the first floor of the exhibition, which is devoted entirely to wider interpretation and family activities.

It was close to the station, where Roulin often worked, and also had a pleasant aspect, opposite the leafy Place Lamartine. Gauguin soon joined him there and for the next two months they enjoyed a fruitful relationship.

In November 1888, Van Gogh decided to paint all five members of the Roulin family, including baby Marcelle in her mother’s arms. Gauguin, too, produced his own somewhat austere portrait of Augustine, and it is interesting to compare his more abstracted approach with Van Gogh’s more personal interpretation.

Saint Louis Art Museum

Rather than pay the family to sit for him on numerous occasions, Van Gogh then embarked on several “repetitions” or variations of his own paintings. The exhibition devotes a whole section to these repeated portraits of the family, inviting the visitor to compare the first version with its copy. Although dating them is a challenge, the repetitions appear more systematic, producing a calmer, more contemplative image, in emulation of Rembrandt.

Particularly curious are two portraits of Marcelle who, with her intense blue eyes and chubby features, takes on an almost grotesque appearance. She is dressed in a white christening robe, with a gold bracelet and pinkie ring, which were common christening gifts.

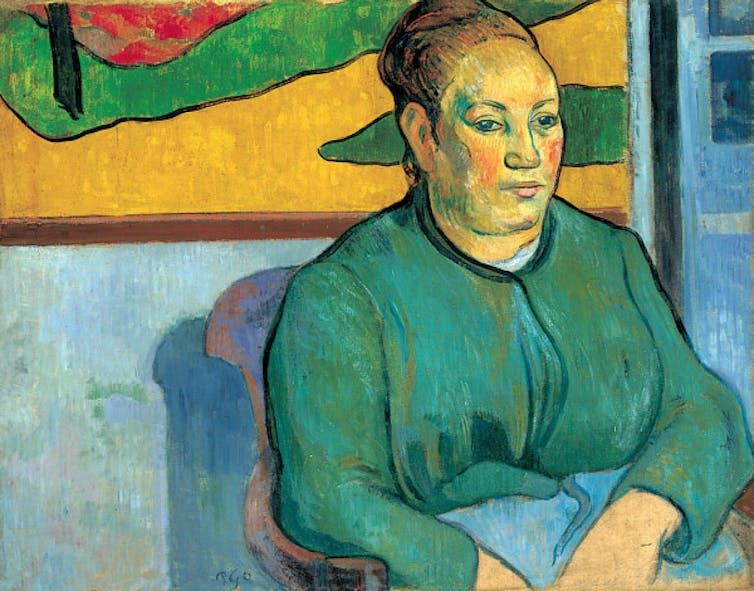

Van Gogh Museum

At the end of December 1888, Van Gogh’s mental state deteriorated dramatically, culminating in him severing most of his left ear with a razor. He was admitted to hospital in Arles, where both Joseph and Augustine paid him regular visits. As a selection of touching letters in the exhibition testify, Roulin also kept in touch with Vincent’s brother Theo.

Once back at the yellow house, Van Gogh continued to work almost obsessively on his repetitions, producing five extraordinary portraits of Madame Roulin, portraying her as the universal symbol of the comforting mother.

Dressed in green, she is seated in a red chair and set against a background of swirling daisies. She holds the rope of a baby’s cradle, evoking the idea of the comforter. Van Gogh even imagined the perfect location for the portrait as the cabin of a ship, where it would rock with the waves, reminding the sailors of their own mother.

This is a wonderful, absorbing exhibition, but with a salutary message. For, before he left Arles, Van Gogh gave the five original Roulin portraits to the postman as a token of their friendship. In 1900, in desperate need of money, Joseph sold all five, together with three other paintings, to the art dealer Ambroise Vollard for a pittance. If only he could have held on to them – today the portraits are recognised as among Van Gogh’s greatest achievements.

Van Gogh and the Roulins – Together Again at Last is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until January 11 2026.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

![]()

Frances Fowle does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Van Gogh and the Roulins: a family reunion of the artist’s greatest portraits – https://theconversation.com/van-gogh-and-the-roulins-a-family-reunion-of-the-artists-greatest-portraits-267349