Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By C. Michael White, Distinguished Professor of Pharmacy Practice, University of Connecticut

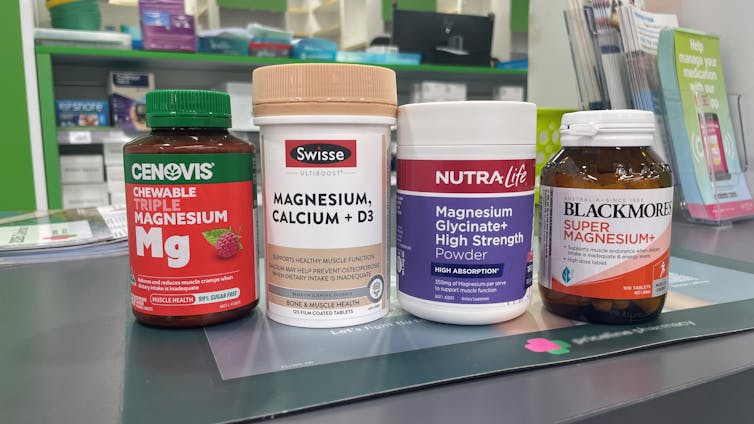

Powder and ready-to-drink protein sales have exploded, reaching over US$32 billion globally from 2024 to 2025. Increasingly, consumers are using these protein sources daily.

A new study by Consumer Reports, published on Oct. 14, 2025, claims that some such protein products contain dangerously high levels of lead, as well as other heavy metals such as cadmium and arsenic. At high levels, these substances have serious, well-documented health risks.

I am a clinical pharmacologist who has evaluated the heavy metal content of baby food, calcium supplements and kratom products. Lead and other heavy metals occur naturally in soil and water, so achieving zero-level exposure would be impossible. Additionally, the level of lead exposure that Consumer Reports deems safe is significantly lower than those set by the Food and Drug Administration.

However, regardless of the safety cutoff, the study does show that a few products are delivering a concerningly high dose of heavy metals per serving.

How Consumer Reports did the study

The new study assessed 23 powder and ready-to-drink protein products from popular brands by sending three samples of each product to an independent commercial laboratory.

Consumer Reports considered anything over 0.5 micrograms per day from any single source to be above recommended maximum lead levels. That number comes from the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, which established recommended maximum levels for a variety of substances that could cause cancer or fetal harm.

It is significantly more conservative than the safety standard for lead exposure used by the FDA for drugs and supplements. The discrepancy is driven by Consumer Reports’ aspirational goals of very low exposure versus the more realistic but actionable requirements from the FDA.

According to the FDA, the limit for the amount of lead that a person should consume from any single dietary supplement product is 5 micrograms per day. That number is 10 times higher than the Consumer Report limit.

The FDA has another standard for the total daily amount of lead a person can safely consume from food, drugs and supplements combined. This number, called the Interim Reference Level, or IRL, for lead is based on concentrations of lead in the blood that are associated with negative health effects in different populations.

For people who could become pregnant, that level is 8.8 micrograms per day, and for children it’s 2.2 micrograms per day. For everyone else, it’s 12.5 micrograms per day. Every food, drug and dietary supplement that contains lead contributes to the total daily exposure, which should be less than this amount.

lakshmiprasad S/iStock via Getty Images Plus

What the report found

The nonprofit advocacy group found that 16 of the 23 products it tested exceeded 0.5 micrograms, the level of lead in a standard serving that the organization deems safe.

Four of the 23 products exceeded 2.2 micrograms, the FDA’s cutoff for the total daily amount of lead children should consume. Two products contained 72% and 88%, respectively, of the total daily amount of lead that the FDA deems safe for pregnant women.

In addition, Consumer Reports found that two of the 23 products delivered more than what it considers a safe amount of cadmium per serving, and one had more arsenic than was recommended.

The organization’s safety cutoff for cadmium is 4.1 micrograms per day, and for arsenic it is 7 micrograms per day. These numbers align fairly closely with the FDA’s recommended exposure limit for cadmium and arsenic from a single product. For cadmium, the FDA’s limit is set at 5 micrograms per day for a given dietary supplement product and 15 micrograms per day for arsenic.

The study found that the source of protein was key: Plant-derived protein products had nine times the lead found in dairy proteins like whey, and twice as much as beef-based protein.

Where are these heavy metals coming from?

Lead and other heavy metals are present in high amounts in volcanic rock, which comes from molten rock called magma beneath the Earth’s surface. When volcanic rock is eroded, the heavy metals contaminate the local soil and water supply. What’s more, some crop plants are especially efficient at extracting heavy metals from the soil and placing them in the parts of the plants that consumers ingest.

Fossil fuels, which come from deep within the Earth, also billow heavy metals into the air when they are burned. These substances then settle out into the soil and water. Finally, some fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides also contain heavy metals that can further contaminate soil and local water.

High levels of heavy metals have been found in plant-based protein powder, spices like cinnamon, dark chocolate, root vegetables like carrots and sweet potatoes, rice, legumes such as pea pods and many herbal supplements.

Virginia State Parks, CC BY

Should consumers be concerned? And what can they do?

Occasionally exceeding the daily recommended heavy metal doses is unlikely to result in serious health issues.

Repeated, heavy exposure to heavy metals can cause harm, however. When they accumulate in the blood, these substances can delay or impair mental functioning, damage nerves, soften bones and raise blood pressure – which in turn increases the risk of strokes and heart attacks. Heavy metals can also increase the risk of developing cancer.

It’s important to note that all the products Consumer Reports flagged have lead levels significantly lower than the maximum daily exposure levels established by the FDA.

Consumers can limit exposure by choosing dairy- or animal-based sources of protein products, since they generally seemed to have less heavy metal contamination than plant-based ones. However, some plant-based protein products in the study did not have high levels of heavy metals. Heavy metal levels vary widely in the environment, so the results from the Consumer Reports study show a snapshot in time. They might not be consistently accurate across batches if, for example, a manufacturer changes the source of its raw ingredients.

For protein products that do show an especially high heavy metal content, using them more sporadically, rather than daily, can reduce exposure. Studies suggest that organic plant-based products generally yield less heavy metal content than traditionally farmed ones.

Finally, the Consumer Reports study measured heavy metals in a single serving of protein products, so it’s helpful to understand what constitutes a serving for specific products and to avoid sharply increasing daily consumption.

Overall, the wide variation in lead levels across different protein powders and ready-made protein products highlights the need for manufacturers to tighten product testing and good manufacturing practices.

![]()

C. Michael White does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Protein powders and shakes contain high amounts of lead, new report says – a pharmacologist explains the data – https://theconversation.com/protein-powders-and-shakes-contain-high-amounts-of-lead-new-report-says-a-pharmacologist-explains-the-data-267591