Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Anna Hudson, Professor, Art History, York University, Canada

Cree artist Kent Monkman is a contemporary old master most celebrated for his reworking of figurative painting. Now in his 60th year, Monkman’s gut-wrenching recastings of images drawn from the western canon are produced by his atelier, a studio modelled on a longstanding tradition of the artist as chef d’atelier.

His 2019 completion of the commission mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (the Met) Great Hall marked the first of three institutional plays by the Met for social relevancy. Monkman, along with African-American contemporary artist Jacolby Satterwhite and Taiwanese calligrapher Tong Yang-Tze, each transformed the vast temple-like lobby into a gathering place for cross-cultural dialogue.

Six years later, Kent Monkman: History is Painted by the Victors, a major retrospective currently on view at the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, positioned mistikôsiwak as the height of Monkman’s boundary-breaking practice and stratospheric rise to the upper echelons of the contemporary international art world.

Monkman’s hired team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous apprentice painters, actors, makeup artists, fashion designers, filmmakers and photographers carry his epic compositions to completion. Their collaborations balance reference to iconic European, Canadian and American nationalist paintings with Monkman’s Cree perspective on the imperial consumption of Indigenous lands.

At their root is Monkman’s commentary on the imposition of western art education in the Americas through the establishment of fine art academies in new nation states to train settler artists.

Fine art and colonialism

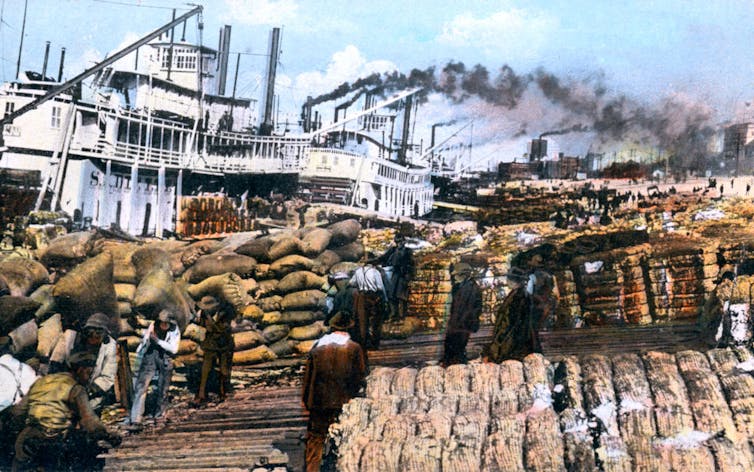

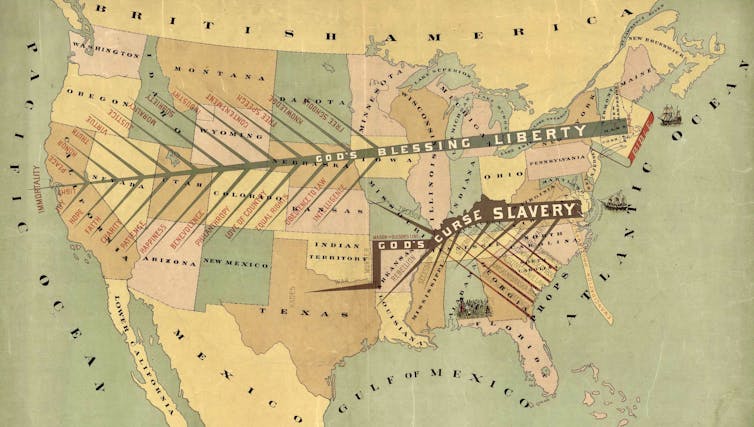

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, landscape painting developed into one of the most celebrated fine art genres. Colonial landowners and governments saw the land around them as a resource to be documented.

Monkman interrupts this by combining two genres — landscape and history painting — to create monumental documents of colliding worldviews: the colonial investment in individual land ownership versus Indigenous land stewardship.

Landscape painting continues to shape Canadian and American national identity. For example, the works of the Canadian Group of Seven are implicated in the idea of Canadian-ness.

Monkman’s approach channels the Romantic painters, and most compellingly, Théodore Géricault’s 1819 The Raft of the Medusa.“ This painting is a canonical composition of bodies caught in the rawest human dynamic of hope versus despair, life versus death — themes interpreted in Monkman’s work. Géricault was controversially unafraid to focus on the dead, diseased and depraved and highlight political incompetence and corruption.

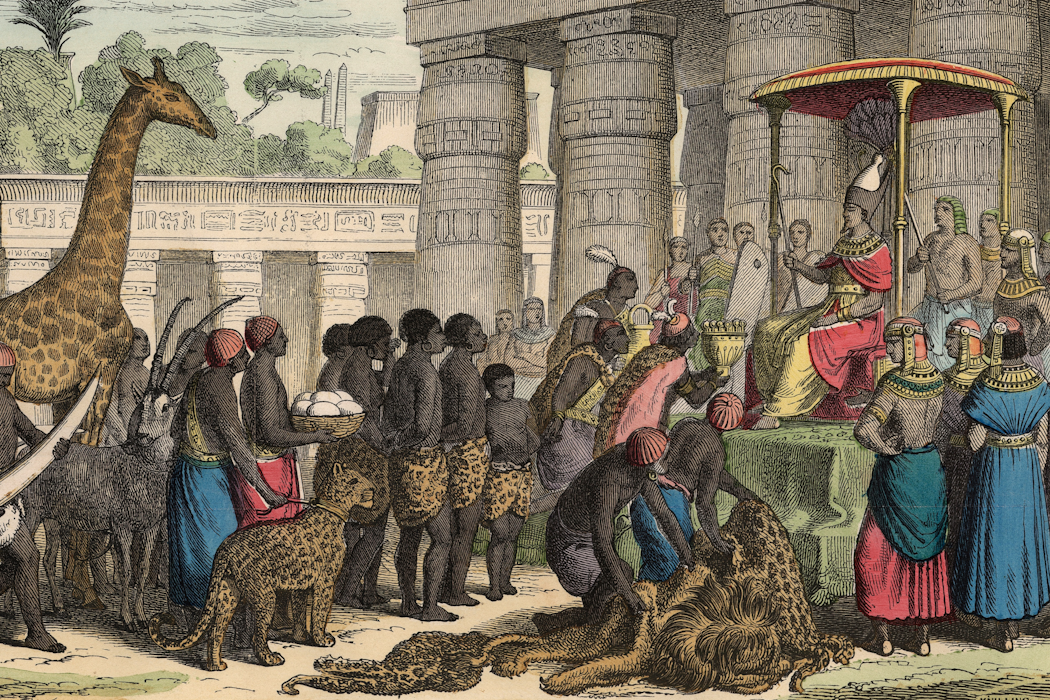

Gericault’s painting records the aftermath of the 1816 shipwreck of the Medusa, a French Royal Navy frigate commissioned to ferry officials to Senegal to formally re-establish French occupation of the colony. As a result of the captain’s inept navigation, the Medusa struck a sandbank off the West African coast. Survivors piled onto a life raft to endure a dehumanizing and deadly 13 days before being rescued by another ship, barely visible on the painting’s horizon.

Response to the canon

Monkman’s 2019 Great Hall commission of two monumental paintings for the Met marked unheard-of success for a contemporary Indigenous artist. As part of the Met’s initiative to invite artists to create new works inspired by the collection in honour its 150th anniversary, the diptych mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) offers a uniquely re-canonizing response to western art history.

This prestigious commission of two monumental paintings, Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People, brought settler reckoning to new audiences in the aftermath of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) 94 Calls to Action.

Given its grand size and public location, mistikôsiwak presented a parallel Indigenous canon, a painterly two-row wampum of sorts that runs alongside its western European historical counterpart towards Indigenous survivance — survival, resilience and endurance — and futurity.

The two-row wampum belt created in the 17th century acknowledged the colonial establishment of two paths: western versus Indigenous. Today, they are entangled by neocolonial industrial pollution and climate change. To artist and curator Rick Hill, this reality, along with the arrival on Indigenous homelands of generations of diaspora populations, brings forth the question: “What is your relationship to this land? What is your relationship to your Native neighbours?”

Given that western and Indigenous definitions of sovereignty remain intractably at odds, Hill’s questions provoke a consideration of land as a shared resource, for humans and non-human life.

Read more:

From the Amazon, Indigenous Peoples offer new compass to navigate climate change

Transformative painting

Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is Monkman’s dynamic anti-colonial trans superhero who often appears in his work. In mistikôsiwak, Miss Chief is represented alongside the arrival of all sorts: colonizers, settlers, servants, slaves, migrants and refugees who never left.

In Resurgence of the People, Monkman riffs off such American idols as Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), depicting George Washington and Continental Army troops crossing the river prior to the Battle of Trenton on the morning of Dec. 26, 1776.

In Monkman’s remaking, Miss Chief captains a boat of survivors who, together, make a spectacle of the Doctrine of Discovery that granted European authority to claim the lands and resources of non-Christian peoples.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau is represented clinging to the boat’s port side, his red tie flailing and his right hand attempting to take control of a paddle. His gold watch is a heart-sinking reminder of the colonial consumption of peoples and land. These representations gesture towards a political versus cultural sense of belonging that underwrote the Liberal government’s 1969 White Paper, which proposed final assimilation of Indigenous Peoples.

In the boat sits Murray Sinclair, the chief commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada who fostered understanding, compassion and reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people in Canada.

Read more:

Carrying the spirit and intent of Murray Sinclair’s vision forward in Treaty 7 territory

Resilience and survival

In Welcoming the Newcomers, Miss Chief is the admonishing figure lifted from the academic tradition who locks eyes with the viewer. Her gaze draws us into the drama unfolding on Turtle Island.

Monkman references the Met’s Watson and the Shark, a 1778 painting by American painter John Singleton Copley recounting a young man’s remarkable rescue from a shark attack. In Monkman’s retelling, the boat is capsized, and only the slave pictured in the original is rescued by Miss Chief, who is bathed in breaking light. In the centre, a muscular figure cradles an Indigenous newborn baby.

In French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix’s early 19th-century painting, The Natchez, also in the Met, a dying baby cradled by a couple signals the massacre of a people. But the washed-up conquistadors scattered along the painted shoreline of Turtle Island remind viewers of more than 500 years of Indigenous resilience. Monkman’s incorporated reference to Delacroix notes the Natchez are alive and well.

Historical revision

Monkman’s paintings present the landscape as a theatrical stage upon which stories of human exploitation play out. Throughout his career, he has consistently transformed European and settler-colonial photography, film, performance and painting into cross-cultural encounters featuring Miss Chief.

Monkman’s goal? To remind settler and diaspora Canadians of their accountability. We share the Earth with each other, human and otherwise, for a collective future.

![]()

Anna Hudson receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) and the Ontario Research Fund (ORF)

– ref. With Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Cree artist Kent Monkman confronts history – https://theconversation.com/with-miss-chief-eagle-testickle-cree-artist-kent-monkman-confronts-history-252136