Source: The Conversation – UK – By John Wyver, Professor of the Arts on Screen, University of Westminster

On the evening of January 26 1926, members of the Royal Institution and other guests climbed three flights of draughty stairs to a tiny workshop in Soho’s Frith Street. They were there to witness the first public presentation of what inventor John Logie Baird called “true television”. A hundred years later, we are now marking the centenary of British television.

Throughout the following 13 years, until the second world war imposed a seven-year hiatus, television developed rapidly. From November 1936 onwards, a regular “high definition” service was transmitted from the BBC’s television station at Alexandra Palace. Alongside countless variety performances and outside broadcasts of pageantry and sports, television established a productively rich relationship with the arts of 1930s Britain.

More than 300 plays were broadcast in these years, including productions of William Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Coward, with appearances by Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Valerie Hobson and Sybil Thorndike among many others. West End productions were restaged in the studio and outside broadcast cameras relayed shows such as J.B. Priestley’s When We Are Married, and the Lupino Lane musical comedy Me and My Girl, to tens of thousands of viewers across London.

This article is part of our State of the Arts series. These articles tackle the challenges of the arts and heritage industry – and celebrate the wins, too.

Artists and architects made frequent appearances, as did a regular selection of classical and contemporary works from London galleries. Other visual artists who featured included Paul Nash, Laura Knight and Wyndham Lewis, along with architects Frank Lloyd Wright, Berthold Lubetkin and Serge Chermayeff. There were numerous performances of opera, including excerpts of contemporary work like Albert Coates’ Pickwick and an ambitious staging of Act 2 of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde.

Once the transmissions could present a full-length figure on the tiny portrait-format screens of the first receiving sets, ballet enjoyed a central presence in TV schedules. Prima ballerinas who performed in the studios included Alicia Markova, Lydia Sokolova and the young Margot Fonteyn.

Touring companies like the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo and the Ballets Jooss made appearances. The troupes benefited from modest fees, exposure and association with modernity’s latest marvel, while television gained cheap access to the best classical dancers of the day as well as cultural credibility.

In so many ways the end of television as we have known it – when YouTube has topped the BBC in viewing share for the first time – could hardly be more different from its pre-war beginnings. But there are also clear continuities across more than half a century, even if early ballroom dancing lessons have morphed into Strictly, and EastEnders is the soap du jour rather than the sedate five-part romance Ann and Harold. One of television’s left behinds, however, is a close relationship with the arts.

The arts on the BBC today

Writing in The Stage in January 2026, critic Lyn Gardner lamented the limitations of television’s coverage of theatre, arguing that “the BBC remains more interested in Glastonbury than the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world’s biggest arts festival” and that the corporation is “more interested in sport rather than culture”.

She also recalled director general Tim Davie’s words from a speech at the Royal Academy in autumn 2024: “The arts remain utterly central to the BBC’s mission. We want to send out a strong signal, that arts and culture matter, they matter for everyone, and they matter even more when times are tough.”

Yet there is no sense that Davie’s words are borne out by the current television schedules. There is no regular slot for imaginative and creative arts documentaries, such as Omnibus which lasted from 1967 to 2003, nor space for reviews and debate, like The Late Show, a nightly arts magazine show that ran throughout the early 1990s. Today’s and tomorrow’s visual artists and performers have only the most minimal presence.

The vanishingly rare presentations of stage work, whether dance, opera or theatre, are invariably acquisitions from cultural organisations that provided most of the funding and all of the production expertise. Complexity and challenging contemporary creativity are almost entirely absent. Far from being “utterly central”, the arts are today utterly marginal to BBC television.

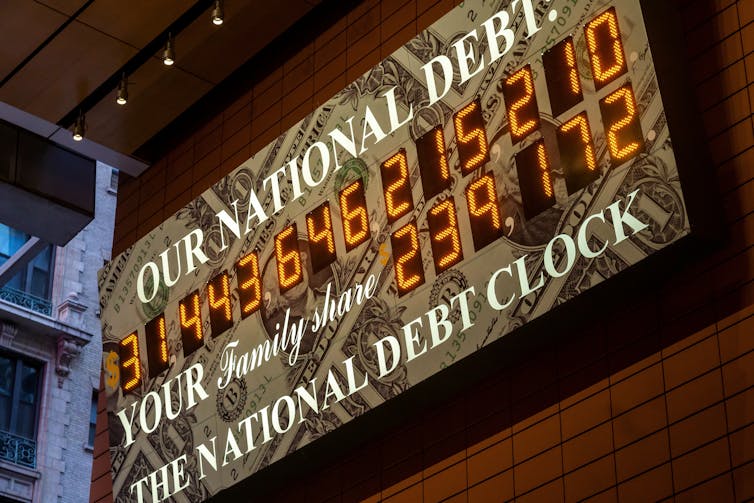

Times are tough, of course, and the BBC faces numerous problems, many of which are the result of a precipitous fall in available funds. Streamers are cannibalising audiences and the licence fee is threatened. The BBC’s response has been to funnel what monies there are to news and current affairs and to high-end drama, which increasingly has to rely on co-production deals.

Television in the pre-war years faced a comparable funding crisis, and yet its producers and executives had confidence and belief in the arts, and were prepared to work collaboratively in partnerships with the cultural institutions of the day. Today, that vision is absent, with little sense of a deep commitment to, or passion for, the arts.

Last year, the BBC sought the views of its audiences with an online questionnaire, and in October a collated report of responses was released as Our BBC, Our Future. In neither the questionnaire nor the report was discussion of the arts “utterly central”.

The arts had next-to-no presence, and as I noted at the time only deep into the report was it acknowledged that: “Among the bigger areas [for which respondents asked] for ‘more’ were: educational content, films and then science and technology, arts and culture and history.”

Fortunately, there is currently a much more substantive and less biased consultation underway. In December, the Department of Culture, Media and Sport published Britain’s Story: The Next Chapter – BBC Royal Charter Review, Green Paper and public consultation, which invites us all to “begin the conversation about how to ensure [the BBC] remains the beating heart of our nation for decades to come”.

In this centenary year for television, this is an important opportunity to express a desire to see the arts returned to the “utterly central” place they occupied in the early years of BBC television.

![]()

John Wyver has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

– ref. The BBC once made the arts ‘utterly central’ to television – 100 years later they’re almost invisible – https://theconversation.com/the-bbc-once-made-the-arts-utterly-central-to-television-100-years-later-theyre-almost-invisible-274162