Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Stanley S. Litow, Adjunct Professor of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University

No industry has perhaps felt the negative effect of a radical shift in federal policy under the second Trump administration more than higher education.

Many American colleges and universities, especially public institutions, have experienced swift and extensive federal cuts to grants, research and other programs in 2025.

Meanwhile, new restrictive immigration policies have prevented many international students from enrolling in public and private universities. Universities and colleges are also facing other various other challenges – like the threat to academic freedom.

These shifts coincide with the broader, increasingly amplified argument that getting a college degree does not matter, after all. A September 2025 Gallup poll shows that while 35% of people rated college as “very important,” another 40% said it is “fairly important,” and 24% said it is “not too important.”

By comparison, 75% of surveyed people in 2010 said that college was “very important,” while 21% said it was “fairly important” and 4% said it is “not too important.”

Still, as a scholar of education, economic development and social issues, I know that there is ample and growing evidence that a college degree is still very much worth it. Graduating from college is directly connected to higher entry-level wages and long-term career success.

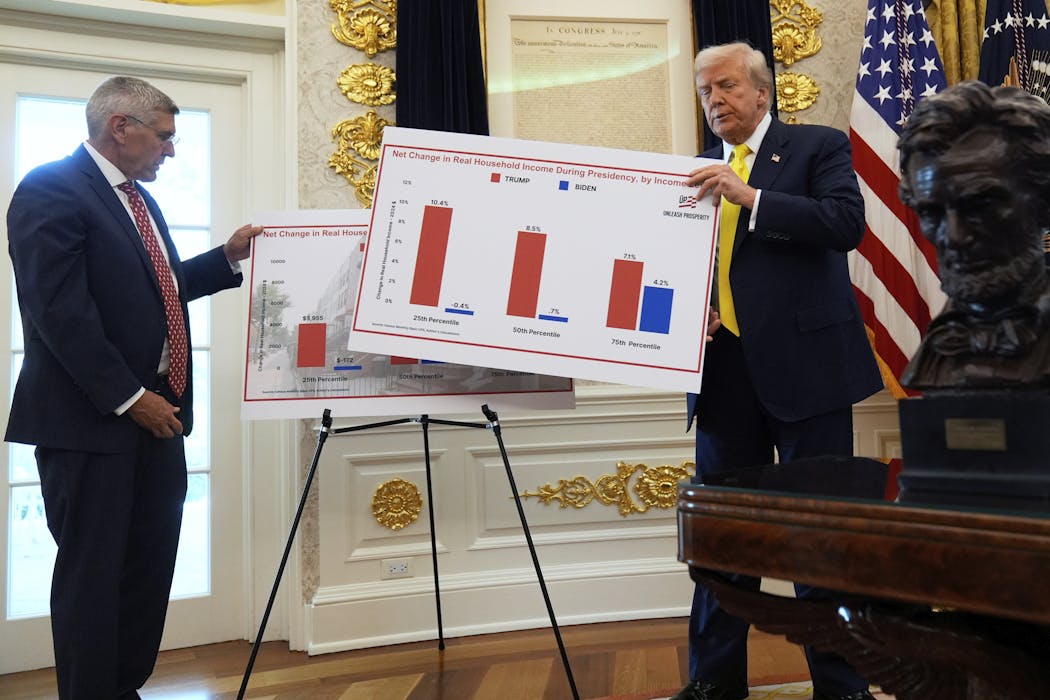

Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images

A growing gap

Some people argue that a college degree does not matter, since there might not be enough jobs for college graduates and other workers, given the growth of artificial intelligence, for example. Some clear evidence shows otherwise.

An estimated 18.4 million workers with a college degree in the U.S. will retire from now through 2032, according to Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. This is far greater than the 13.8 million workers who will enter the workforce with college degrees during this same time frame.

Meanwhile, an additional 700,00 new jobs that require college degrees – spanning from environmental positions to advanced manufacturing – will be created from now through 2032.

The gap between those expected to leave and enter the workforce with college degrees creates a serious problem. One major question is whether there will be enough people to fill the available jobs that require a college degree.

In 2023, foreign-born people made up 16% of registered nurses in the U.S., though that percentage is higher in certain states, like California. But restrictions on immigration could limit the number of potential nurses able to fill open positions.

Nursing and teaching are two fields expected to grow over the next few decades, and they will require more workers due to retirements.

Other fields, like accounting, engineering, law and many others, are also expected to have more college-educated workers retire than there are new workers to fill their positions.

Worth the cost

The average annual salary of a college graduate from the class of 2023 was US$64,291 in 2024, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers.

The overall average salary for this graduation class one year after they left school marked an increase from the average $60,028 that the class of 2022 earned in 2023, equivalent to $63,850 today.

While there is not available data that offers a direct comparison, full-time, year-round workers ages 25 to 34 with a high school diploma earned $41,800 in median annual earnings in 2022, or $46,100 today.

Overall lifetime earnings for those with college degrees is about about $1.2 million more than people with a high school make, according to the recent Georgetown findings.

People who earn more generally have more money to support their families and contribute to their immediate communities. Their higher taxes also contribute to the U.S. economy, supporting needed services like education, public safety and health care.

People with college degrees are also more likely than those who are not college graduates to vote, volunteer and make charitable donations to help others in need.

College matters for individuals, but it clearly also helps improve the economy.

With 64 public colleges across the state, the State University of New York system is the largest post-secondary network of higher education schools in the country. For every $1 the state of New York invests in SUNY, the SUNY system returns $8.70 to the state in terms of economic growth, according to 2024 findings by the Rockefeller Institute, an independent public policy research organization affiliated with SUNY. And that is only one state.

Howard Schnapp/Newsday RM via Getty Images

A new way forward

It isn’t likely that the expected number of college-educated people who will soon retire will suddenly decrease, or that the anticipated number of people entering the workforce will unexpectedly increase.

There are practical reasons why some people do not want to go to college, or cannot attend. Indeed, the percentage of young people enrolled as college undergraduates fell almost 15% from 2010 through 2022.

For one, tuition and fees at private colleges have increased about 32% since 2006, after adjusting for inflation. And in-state tuition and fees at public universities have also grown about 29% since 2006.

The total of federal student loan debt for college has also tripled since 2007. It stood at about $1.84 trillion in 2024.

I believe that in order to ensure enough college-educated people can fill the anticipated work openings in the future, universities and the government should embrace needed changes to increase both enrollment and completion rates.

Artificial intelligence will transform work worldwide, for example, and that shift should be incorporated into higher education curriculum and degrees. Soft skills – like problem-solving, collaboration, presentation and writing skills – will become more important and should be prioritized in the learning process.

I believe that universities should also prioritize experiential education, including paid internships that offer students academic credit. This can help students gain experience that is both accredited and is connected to direct career pathways.

Universities and high schools could also expand how much they offer microcredentials – or short, focused learning programs that offer practical skills in a specific area – so students can connect their education with clear career pathways.

These reforms aren’t easy. They require a commitment to change, and all of this work will require deep partnerships with the government. While that might be a heavy lift currently at the federal level, it is both possible and achievable to make advances on these and other changes at the state level.

American universities and colleges have always been key to preparing the workforce for economic opportunity. At the end of World War II, for example, Columbia University and IBM worked together to help create the academic discipline now called computer science.

This action did more than help one university or one employer. It fueled change across higher education and across private companies and the government, leading to massive economic growth.

Universities have made countless other contributions to strengthen and expand the economy. Considering solutions to some of the challenges that stop students from going to college could help ensure that more students see the value in a college education – and a tangible way for them to connect it to a future career.

![]()

Stanley S. Litow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Despite naysayers and rising costs, data shows that college still pays off for students – and society overall – https://theconversation.com/despite-naysayers-and-rising-costs-data-shows-that-college-still-pays-off-for-students-and-society-overall-267612