Source: The Conversation – USA – By Michelle L.D. Hanlon, Professor of Air and Space Law, University of Mississippi

When Apollo 13 looped around the Moon in April 1970, more than 40 million people around the world watched the United States recover from a potential catastrophe. An oxygen tank explosion turned a planned landing into an urgent exercise in problem-solving, and the three astronauts on board used the Moon’s gravity to sling themselves safely home. It was a moment of extraordinary human drama, and a revealing geopolitical one.

The Cold War space race was a two-player contest. The Soviet Union and the United States operated in parallel, rarely cooperating, but clearly measuring themselves against one another. By 1970, the United States had already landed on the Moon, and competition centered on demonstrating technological capability, political and economic superiority and national prestige. As Apollo 13 showed, even missions that did not go as planned could reinforce a country’s leadership if they were managed effectively.

More than half a century later, NASA’s Artemis II mission will send humans around the Moon again in early 2026, this time deliberately. But the strategy going into Artemis II looks very different from that of 1970. The United States is no longer competing against a single rival in a largely symbolic race.

NASA, CC BY-NC

As a professor of air and space law, I research questions of governance and conflict avoidance beyond Earth. From a space law perspective, sustained human activity on the Moon and beyond depends on shared expectations about safety and responsible behavior. In practice, the countries that show up, operate repeatedly and demonstrate how activity on the lunar surface and in outer space can be carried out over time shape these expectations.

Artemis II matters not as nostalgia or merely a technical test flight. It is a strategic signal that the United States intends to compete in a different kind of Moon race, one defined less by singular achievements and more by sustained presence, partnerships and the ability to shape how activity on the Moon is conducted.

From a 2-player race to a crowded field

Today, more countries are competing to land on the Moon than ever before, with China emerging as a pacing competitor. While national prestige remains a factor, the stakes now extend well beyond flags and firsts.

Governments remain central actors in the race to the Moon, but they no longer operate alone. Commercial companies design and operate spacecraft, and international partnerships shape missions from the start.

China, in particular, has developed a lunar program that is deliberate, well-resourced and focused on establishing a long-term presence, including plans for a research station. Its robotic missions have landed on the Moon’s far side and returned samples to Earth, and Beijing has announced plans for a crewed landing by 2030. Together, these steps reflect a program built on incremental capability rather than symbolic milestones.

Why Artemis II matters without landing

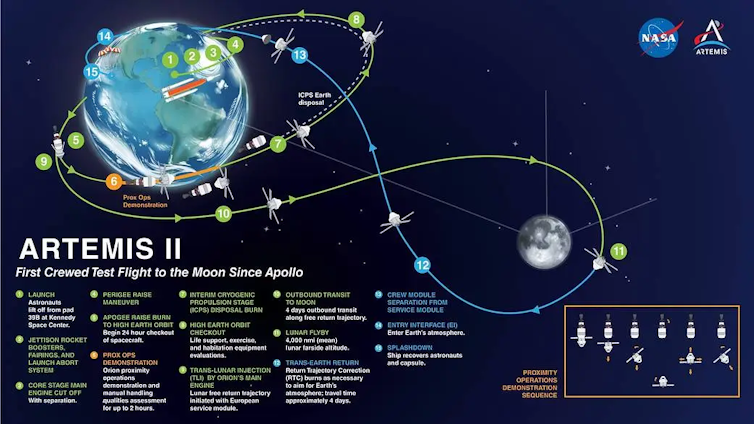

Artemis II, scheduled to launch in February 2026, will not land on the Moon. Its four-person crew will loop around the Moon’s far side, test life-support and navigation systems, and return to Earth. This mission may appear modest. Strategically, however, crewed missions carry a different weight than robotic missions.

NASA

Sending people beyond low Earth orbit requires sustained political commitment to spaceflight, funding stability and systems reliable enough that sovereign and commercial partners can align their own plans around them.

Artemis II also serves as a bridge to Artemis III, the mission where NASA plans to land astronauts near the Moon’s south pole, currently targeted for 2028. A credible, near-term human return signals that the U.S. is moving beyond experimentation and toward a sustained presence.

2 different models for going back to the Moon

The contrast between U.S. and Chinese lunar strategies is increasingly clear.

China’s program is centrally directed and tightly controlled by the state. Its partnerships are selective, and it has released few details about how activities on the Moon would be coordinated with other countries or commercial actors.

The U.S. approach, by contrast, is intentionally open. The Artemis program is designed so partners, both other countries and companies, can operate within a shared framework for exploration, resource use and surface activity.

This openness reflects a strategic choice. Coalitions among countries and companies expand their capabilities and shape expectations about how activities such as landing, operating surface equipment and using local resources are conducted.

When vague rules start to matter

International space law already contains a framework relevant to this emerging competition. Article IX of the 1967 outer space treaty requires countries to conduct their activities with “due regard” for the interests of others and to avoid harmful interference. In simple terms, this means countries are expected to avoid actions that would disrupt or impede the activities of others.

For decades, this obligation remained largely theoretical. On Earth, however, similarly open-ended rules, particularly in maritime contexts, created international conflicts as traffic on shipping lanes, resource extraction and military activity increased. Disputes intensified as some states asserted claims that extended beyond what international law recognized.

The Moon is now approaching a comparable phase.

As more actors converge on resource-rich regions, particularly near the lunar south pole, due regard becomes an immediate operational question rather than a theoretical future issue. How it is interpreted – whether it means simply staying out of each other’s way or actively coordinating activities – will shape who can operate where, and under what conditions.

Washington is naming the race − without panic

During his second Senate Commerce Committee confirmation hearing, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman was asked directly about competition with China in lunar exploration. He emphasized the importance of keeping U.S. space efforts on track over time, linking the success of the Artemis program to long-term American leadership in space.

A similar perspective appears in a recent U.S. government assessment, the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s 2025 annual report to Congress. Chapter 7 addresses space as a domain of strategic competition, highlighting China’s growing capabilities. The report frames human spaceflight and deep-space infrastructure – including spacecraft, lunar bases and supporting technologies – as part of broader strategic efforts. It emphasizes growing a human space program over time, rather than changing course in response to individual setbacks or the accomplishments of other countries.

Joel Kowsky/NASA via Getty Images

Recent U.S. policy reflects this emphasis on continuity. A new executive order affirms federal support for sustained lunar operations, as well as commercial participation and coordination across agencies. Rather than treating the Moon as a short-term challenge, the order anticipates long-term activity where clear rules, partnerships and predictability matter.

Artemis II aligns with this posture as one step in the U.S.’s plans for sustained activity on the Moon.

A different kind of test

As Artemis II heads toward the Moon, China will also continue to advance its lunar ambitions, and competition will shape the pace and manner of activity around the Moon. But competition alone does not determine leadership. In my view, leadership emerges when a country demonstrates that its approach reduces uncertainty, supports cooperation and translates ambition into a set of stable operating practices.

Artemis II will not settle the future of the Moon. It does, however, illustrate the American model of space activity built on coalitions, transparency and shared expectations. If sustained, that model could influence how the next era of lunar, and eventually Martian, exploration unfolds.

![]()

Michelle L.D. Hanlon is affiliated with For All Moonkind, Inc. a non-profit organization focused on protecting human cultural heritage in outer space.

– ref. NASA’s Artemis II crewed mission to the Moon shows how US space strategy has changed since Apollo – and contrasts with China’s closed program – https://theconversation.com/nasas-artemis-ii-crewed-mission-to-the-moon-shows-how-us-space-strategy-has-changed-since-apollo-and-contrasts-with-chinas-closed-program-270245